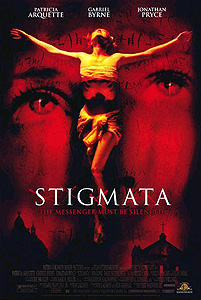

Stigmata (1999) **

Stigmata (1999) **

By 1999, it had been a long, long time since the world had seen an honest-to-God Exorcist knock-off. But since that year’s horror boom produced slasher movies, ghost movies, Jaws rip-offs, and even the first Universal Studios mummy flick in 44 years, it would have been unseemly not to give the venerable possession story another go-round. Stigmata is on most counts a fairly standard example of the form, and despite a certain technical solidity, it is not especially good. It suffers from overly hectic, MTV-influenced editing, an immediately obvious “surprise” villain, an undue level of attention given to given to gore effects which are often jarringly shoddy, and a truly remarkable lack of intellectual follow-through regarding the broader implications of its story— especially as concerns its uncritical acceptance of one pivotal character’s ultimate goodness, even though his actions are uniformly and unambiguously evil. (Then again, since that character is acting on behalf of a god who is worshipped by hundreds of millions the world over, even though his behavior as described in holy writ is also unambiguously evil more often than not, maybe such a treatment is only to be expected.) That last is all the more troublesome considering what an increasingly big deal Stigmata makes of its increasingly overt socio-theological message as the film wears on. There is one sense in which it unquestionably stands out from the crowd, however— I know of no other film in which the heroine is possessed not by the Devil, but by the spirit of a messianically obsessed ex-Roman Catholic priest!

The first half of the credits roll over a montage of an old man in a monk’s cassock (Jack Donner, from Cool Air and Soulkeeper) hard at work over a scroll which is thickly covered with writing in some obviously ancient script. Then we move on to the arrival in Belo Quinto, Brazil, of Father Andrew Kiernan (Gabriel Byrne, from Excalibur and End of Days). Kiernan is no ordinary priest; he’s also a scientist, and the Vatican makes use of his training by sending him out to investigate claims of miracles. In Belo Quinto, you see, there is a small church with a marble statue of the Virgin Mary that bleeds continuously from the eyes, and word of this remarkable object has brought Kiernan to town on a detour from the more mundane investigation he was officially supposed to be making. (It’s moments like this when I realize how utterly sensible it is that Roman Catholicism caught on so well in Latin America. It was just about the only place in the world where Catholicism would have seemed less extravagantly gruesome than the homegrown religions…) The boss-man at Our Lady of the Copiously Bleeding Eyeballs is one Father Alameida, and as you might already have surmised, he is the man we saw studying the scroll during the credits. He’s also recently dead, and it was right after he kicked it that the statue of Mary in his church started doing tricks. A quick look at the statue convinces Kiernan that it is quite possibly the real deal, and he begins trying to make arrangements for more thorough study. Meanwhile, in a seemingly unrelated development, a typical Ugly American in the Belo Quinto marketplace buys the rosary which belonged to Father Alameida for her daughter back home in Pittsburgh.

That daughter back in Pittsburgh is named Frankie Paige (Patricia Arquette, from A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors), and the rosary arrives in the mail just as we are meeting her. By day, Frankie cuts hair at a downtown beauty shop. By night, she goes clubbing with her coworkers, Donna (Buried Alive’s Nia Long) and Jennifer (Portia De Rossi, of Scream 2 and Cursed), and alternately fucks and fights with her boyfriend, Steven (Patrick Muldoon, from Starship Troopers). What she most emphatically does not do is go to church, or indeed even believe in God. Consequently, it would seem to require even more explaining than usual when Frankie begins exhibiting stigmata. One night, while she soaks in the bathtub after her usual evening on the town, there is a strange atmospheric disturbance in her apartment, a white dove (that traditional Catholic representation of the Holy Spirit) flies in from who knows where, and some unseen force drags Frankie down under the water and holds her there. Frankie then has a vision of somebody driving iron spikes through somebody else’s wrists, and is walloped by a wave of intense pain from her own. The unseen force lets go of her at that point, leaving her to tend to the spurting puncture wounds that now inexplicably pierce her wrists the whole way through. Her friends and the doctor who treats her at the hospital assume the injuries stem from a suicide attempt, but as Frankie herself protests, she cuts hair— how much stress can there possibly be in her life?

The holes in Frankie’s wrists are just the beginning. At work the next day, Frankie— whose biggest worry up to now had been that her period was late— sees a woman in white who looks more than a little like her stop on the sidewalk across from the beauty shop and drop a baby dressed in red into the street. Frankie rushes out to rescue the infant, but it isn’t there when she reaches the spot. In fact, Donna tells her it was never there, nor the woman either. (Incidentally, this business about possible pregnancies and baby-dropping apparitions will vanish without a trace from the story almost instantly upon being introduced.) Then, as Donna is escorting Frankie home on the subway, there is a second outburst of supernatural violence, in which it appears that something invisible is whipping Frankie, shredding both her jacket and the flesh of her back. And as it happens in a relatively crowded train car, this time there are witnesses to the fact that Frankie sure as hell isn’t hurting herself. One of those witnesses is a Catholic priest named Father Durning (Thomas Kopache), for whom the nature of the girl’s uncanny wounds rings any number of bells. Durning drops a line to the Vatican, telling them that he believes he may have discovered a stigmatic in Pittsburgh.

Reenter Father Kiernan. The Church’s official position that stigmata are a gift from God to the exceptionally devout puts the supernatural affliction in his department, and he seeks Frankie out to discuss the situation with her. Needless to say, he doesn’t quite know what to make of Frankie’s claims to have recently written a piece of devotional poetry in Italian (which she does not normally speak) while in a trance state, and he’s totally flummoxed to hear that this young woman whose preternatural injuries unmistakably mimic the wounds of Christ is not only a non-Catholic, but a professed atheist. And while that technically puts Frankie’s stigmata outside of Kiernan’s field of expertise, he nevertheless continues to monitor the girl’s case— as both a scientist and a priest, he can’t help but be captivated by the puzzle she poses. Eventually, Kiernan pays a visit to the Vatican library, where he compares notes with Father Dario (Enrico Colatoni, of A.I.: Artificial Intelligence), an old friend of his who works as one of the institution’s translators. Dario has never heard of an atheist stigmatic, either, but he finds the verse which Frankie unconsciously wrote to be vaguely familiar.

That’s not the only strange thing Frankie’s going to be writing, either. Right after she gets the crown of thorns to go with her nail and flogging wounds, she zones out completely, and Kiernan finds her in the alley behind her apartment building, scratching strange symbols in the hood of a car and speaking in tongues. Kiernan has his tape recorder on him, and he is able to catch a great deal of what Frankie says before she snaps out of it. When he plays the tape over the phone for Father Dario, the old man identifies the language as Aramaic— specifically, as the Galilean dialect which Jesus himself most likely spoke. Another descent into a trance causes Frankie to scrawl a veritable treatise in Aramaic across the wall of her kitchen, and those who were paying attention early on will immediately recognize the text from that scroll Father Alameida was poring over back in Brazil. We may therefore assume that the masculine voice in which Frankie berates Father Kiernan when he walks in on her (and in which she shouts taunts and curses at him while kicking the crap out of him immediately thereafter) belongs to Alameida, too, in which case I’d say we now know exactly who it is that is causing Frankie all of her supernatural difficulties. Nor will it surprise us in the slightest later on when we hear that Alameida was himself a stigmatic. Then, a day or two later, after Kiernan faxes the photos he took of Frankie’s wall to Father Dario, we’ll get some idea of why Alameida is making such a pest of himself. Though he refuses to tell Kiernan this out of fear for the safety of all concerned, Dario has seen that particular Aramaic text before. Some years ago, he was assigned, along with Alameida and a third priest named Petroceli (Rade Sherbedgia, from the remakes of Mighty Joe Young and The Fog), to translate a first-century Aramaic scroll; it was a hitherto unknown gospel, and there was some indication that it might have been written by Jesus himself! If that were true, however, then the specific content of the scroll would have been more than a little inconvenient for the Catholic Church, as its message was explicitly populist and anti-authoritarian, espousing a model for church organization which had much more in common with backwoods American Pentecostalism than it did with what the various popes had worked out over the past couple thousand years. Dario’s superior, Cardinal Houseman (Jonathan Pryce, of The Doctor and the Devils and Something Wicked This Way Comes), ordered a halt to the translation project, and when Alameida and Petroceli refused, they were both defrocked and excommunicated. Alameida snuck off to Brazil, taking the disputed scroll with him, and presumably spent the rest of his life completing the translation in secrecy. And now that he’s dead, Alameida is presumably seeking to use Frankie as an instrument to get the world’s attention. Of course, getting the world’s attention means getting Cardinal Houseman’s attention, too, and if 30 years’ worth of possession and devil-worship movies have taught us anything, it’s that the Roman Catholic Church is the ecclesiastical equivalent of the CIA. Houseman’s direct involvement can’t be a good thing for anybody.

Generally speaking, I much prefer horror movies that take themselves seriously to those that don’t. But as with all other realms of human endeavor, there is such a thing as overdoing it. Stigmata overdoes it in ways I’ve not seen in years. This movie is simply bursting at the seams with a hypertrophied sense of its own importance, to the extent that it makes even its most obvious model, the notoriously dour and humorless The Exorcist, look like something New World Pictures would have released around the turn of the 80’s. It’s difficult to imagine where director Rupert Wainwright and screenwriters Tom Lazarus and Rick Ramage might have gotten the idea that such an attitude toward this movie was warranted, since it has little beyond its virulently anti-Catholic premise to distinguish it from any number of films which nobody ever took seriously at all. But then, just before the closing credits, we are presented with the following caption, and it all snaps into place:

In 1945, a scroll was discovered in Nag Hammadi, which is described as “the sayings of the Living Jesus.” This scroll, the Gospel of St. Thomas, has been claimed by scholars around the world to be the closest historical record we have of the words of the historical Jesus. The Vatican refuses to recognize the gospel, and has described it as heresy. |

Ummm… Not exactly. And if you read between the lines to square that caption up with the events of the film that it brings to a close, then really not exactly. The Gospel of Thomas was indeed found sealed in a big ceramic jar at the foot of a cliff in Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in 1945, and it does indeed begin with the phrase, “These are the words of the Living Jesus.” It is also true that the Gospel of Thomas was rejected as heretical by the Catholic Church. But virtually everything else suggested about the book from the combination of that caption and the film which precedes it is wrong. To begin with the truly pedantic, the Gospel of Thomas was not written on a scroll, but was rather part of a codex— essentially a book as we understand the term today— in which it was bound together with a number of other religious tracts. That codex was part of an entire library, containing twelve complete volumes plus a few loose pages apparently torn from a thirteenth. The age of the books themselves can be dated to no earlier than the middle of the fourth century A.D., and they were written not in Aramaic, but in Coptic (a form of antique Egyptian written with a variation on the Greek alphabet), seemingly in translation from Greek originals which are now mostly lost. Those Greek versions would, of course, have been older, and in the case of the Gospel of Thomas, a composition date in the second century is likely, and a first-century authorship is not out of the question. Consequently, it is within the realm of possibility that, chronologically speaking, the Gospel of Thomas gets us closer to what Jesus actually said than any of the four canonical gospels. But it is a long road from there to the notion that it gives a more accurate rendering of Christ’s message, and from the circumstances of the gospel’s discovery— hidden in a sealed jar beneath a boulder at the foot of a forbidding cliff in one of the remotest habitable regions of Egypt— it seems safe to conclude that it had already been forcefully repudiated by mainstream Christianity as early as the time of Constantine. Finally, despite the prominent use of a direct quote from the scripture in the movie (Frankie’s trance poem is from Thomas, verse 77), the Gospel of Thomas is not at all the book which Stigmata implies.

Far from being a programmatic treatise on church organization, the Gospel of Thomas is really nothing more than a rather disorderly compilation of quotes attributed to Jesus— most of them cryptic, many redundant, some contradictory, and a few frankly nonsensical. About half of those quotations appear in slightly different form in Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John, and the ones that don’t (which are the more interesting ones for our present purposes) might be taken to imply a religious order that is actually more abstruse and more hierarchical even than Roman Catholicism! For the Gospel of Thomas, like the rest of the Nag Hammadi library, is a Gnostic text, promising salvation through neither faith nor good works, but through the mastery of arcane and mystical knowledge— verse 2 comes right out and promises “Whoever finds the interpretation of these sayings will not experience death.” Gnostic religions, whether based in Christianity, Judaism, or the Mithraic Mysteries, are inherently elitist, for they cannot function without an upper caste of adepts to explain and interpret their arcana. The Jesus of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John may speak in parables, but the Jesus of Thomas speaks in riddles. What’s more, the Gospel of Thomas strongly implies that the ranks of the saved will be thin indeed, with much talk of “the elect” and numerous metaphors of winnowing and discarding. A church in which a favored remnant of humanity is kept on the straight and narrow by an even tinier priesthood of spiritual savants could hardly be more obviously at variance from the message of direct and inclusive contact between God and believer put forth by Stigmata’s fictional Gospel of Jesus, and the filmmakers’ implicit equation of their imaginary gospel with the real-world Gospel of Thomas can only make me question whether Wainwright, Lazarus, and Ramage ever went to the trouble of actually reading the thing!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact