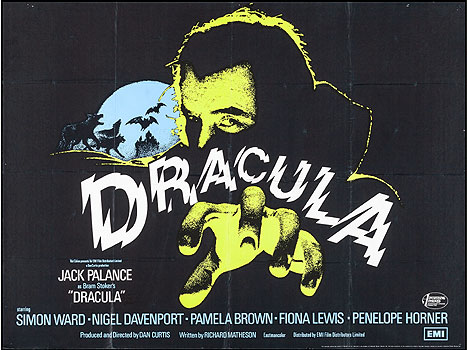

Dracula (1973/1974) **½

Dracula (1973/1974) **½

I suspect that Dan Curtis could smell blood in the water that summer. He spent much of 1973 piggybacking an entire series of made-for-TV adaptations of classic 19th-cenury horror novels onto his 1968 version of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, beginning with Frankenstein, continuing with The Picture of Dorian Gray and Dracula, and finally wrapping up with The Turn of the Screw early in 1974. Three of the four pictures were produced to the same standard as the Jekyll and Hyde film: shot on videotape, entirely on soundstages and studio back lots, with casts drawn largely from a rogues’ gallery of recidivist TV guest stars, and no ambition to look like anything much more grandiose than a Sweeps Week episode of a weekly prime-time television drama. For Dracula, though, Curtis aimed much higher. He sent the production not just to the UK in search of budget-stretching wage and currency-exchange rates, but also to Yugoslavia for authentic landscapes and local color. In place of the Guest Spot Reserve Army regulars, he cast the picture with a stable of recognizable (if by no means famous) British character actors, and brought in Jack Palance— his old Dr. Jekyll— to play the title role once again. He commissioned Richard Matheson to write the script, injecting some star power behind the camera as well. Most of all, he shot the whole thing on 35mm film, with frame compositions contrived to work equally well on television or cinema screens, and even filmed gorier alternate takes of several vampire deaths in order to make Dracula more attractive to theatrical distributors overseas. It all seems a strange departure from form until you remember that Curtis’s Frankenstein wasn’t the only version of that tale to make its television debut in 1973. I think Curtis must have realized that Frankenstein: The True Story was about to put his interpretation permanently in the shade, and wanted to be ready with a riposte. Indeed, what Curtis was planning was even better than a riposte, because Dracula was scheduled for initial broadcast on the night of October 12th— fully a month and a half before part one of Frankenstein: The True Story. Fate was against Curtis on this occasion, however, for when premiere night rolled around, CBS bumped Dracula from the broadcast schedule in favor of extended breaking-news coverage of Spiro Agnew’s unprecedented resignation from the vice presidency of the United States. Turns out the hunt for an imaginary bloodsucker just couldn’t compete with a real one getting caught. Dracula sat on the shelf until the following February, which may go some way toward explaining the return to traditional teleplay production standards for The Turn of the Screw that spring. Still, although Dracula got skunked out of the bragging rights it was designed to claim, it seems to have developed the most durable cult following of the whole classic-horror-on-70’s-TV cycle, thanks to Matheson’s thoughtful writing and a memorably strange performance from the wildly miscast Palance.

Real estate agent Jonathan Harker (Hardcore’s Murray Brown) arrives in the Transylvanian mountain town of Bistritz, en route to the castle of Count Dracula (Palance, from Alone in the Dark and Without Warning) somewhere in the wilderness between there and Bukovina. The count is planning on relocating to England, and Harker has come to broker the sale of some suitable property. In fact, however, Jonathan is walking into a trap, and his experience of captivity to the undead won’t be nearly as much fun as that which a different Murray Brown character would endure in Vampyres not much later. Once Dracula has selected a house from the portfolio of a dozen or so grand estates whose photographs and particulars Harker shows him (the count rather likes a dilapidated old place in Whitby called Carfax), the estate agent will find that his main value to his customer is as a walking pantry from which to build up his strength for the journey from Transylvania to England. Then, once he’s ready to embark, Dracula will turn whatever’s left of Harker over to the ladies of his harem (Virginia Weatherell, from Demons of the Mind and The Crimson Cult, Sarah Douglas, from The Return of Swamp Thing and The Last Days of Man on Earth, and Barbara Lindley, of Escort Girls and Lady Chatterley vs. Fanny Hill) to finish off. The voyage takes five weeks, most of them aboard a Russian schooner called the Demeter, and by the time the ship reaches Dracula’s destination, there’s no one aboard left alive to guide her into port. As you might well imagine, a foreign ship beaching itself, manned only by a single corpse and with all the cargo on the manifest accounted for except for ten big boxes of dirt, is the talk of the town in Whitby for quite some time.

Count Dracula probably wasn’t lying to Harker when he said he found the age and disrepair of Carfax homey, but the real reason why he chose it over all the other houses was strictly a matter of location. It happens to stand less than ten miles away from the estate of a family called Westenra, the daughter of which is the dearest friend of Jonathan’s fiancée, Mina Murray (Penelope Horner, of Holocaust 2000 and The Devil’s Daffodil). Harker brought with him to Transylvania a group photo of him, Mina, the aforementioned Lucy Westenra (Fiona Lewis, from Lisztomania and Strange Behavior), and Lucy’s fiancé, Arthur Holmwood (Simon Ward, of Dominque Is Dead and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed), and Dracula took a pronounced interest in Lucy when he saw it. You see, when the count was alive in the mortal sense 400-odd years ago, he was married or betrothed or something to a woman named Maria, who died tragically young. Soullesss, bloodsucking fiend he may be, but Dracula has never gotten over the loss in all those centuries. And Lucy, wouldn’t you know it, looks exactly like Maria. The vampire begins paying regular nocturnal visits to his pretty neighbor just as soon as he’s settled in at Carfax, with an eye toward “reuniting” himself in undeath with the woman he loved in life (or at least with a plausible facsimile of her). Within three weeks or so, the girl is in such poor health that her mother (Pamela Brown, from The Night Digger and Secret Ceremony) and Arthur alike are beside themselves with worry.

Fortunately, Holmwood knows a doctor of considerably greater experience and acumen than the provincial sawbones who’s been trying and failing to treat Lucy so far— fellow by the name of Van Helsing (Nigel Davenport). Although he affects a reassuring demeanor during his initial examination, Van Helsing’s assessment of his new patient’s condition is grave indeed. As he tells Arthur soon thereafter, if his suspicions are correct, Lucy would be better off had the strange wound on her neck that unaccountably refuses to heal been the work of the most venomous serpent on Earth. If that’s so, though, then Holmwood can’t understand why Van Helsing won’t just come out and say what he thinks is going on. Heaven knows his prescriptions so far— crosses hung on all the exterior doors and windows in the house, wreath of garlic flowers to be strung round Lucy’s neck all night long, and above all the strictest measures to curb her recent habit of walking in her sleep— are difficult to square with any illness that Arthur has ever heard of. But the doctor discloses the true nature of his fears for Lucy’s safety only upon one calamitous morning when he and Arthur find her out in the garden, near death from inexplicable blood loss, after they both fell asleep during what was supposed to have been the final hour of their dusk-to-dawn vigil over her. Now more than ever, it’s clear to Van Helsing that Lucy has fallen prey to a vampire.

Holmwood’s instinct is to scoff, but it isn’t as though he has any better ideas to explain where three quarters of his fiancée’s blood disappeared to just before dawn. After a round of transfusions gets the girl’s veins topped up again, Van Helsing turns to modern pharmacology to make certain there are no repeats of that morning’s near-fatal fiasco. (Matheson never says in as many words that Holmwood and Van Helsing start doing cocaine, but they totally start doing cocaine.) And sure enough, once Lucy’s guardians are able to stay awake reliably enough to keep her in bed the whole night through, she begins a truly remarkable recovery. At the end of three months, the doctor is ready to pronounce his patient cured.

The trouble with incipient vampirism, however, is that the only sure way to prevent a relapse is to destroy the vampire that was attempting to pass on its condition. Leaving Holmwood in charge of Lucy’s care in the interim, Van Helsing goes home to gather up whatever research materials he deems necessary for the mission of extermination to come. But while the doctor is thus occupied, Dracula at last devises a way to circumvent the defenses keeping Lucy out of his reach. He liberates a wolf from the local zoo, and commands it to mount a frontal assault on the Westenra house. Then, while Arthur and the servants deal with that unexpected threat, the vampire lures his victim out onto the estate grounds, and positively gorges himself on her blood. There’ll be no bouncing back for Lucy this time.

On the night following her funeral, however, Lucy emerges from the Westenra family crypt, and comes to see Arthur. Holmwood is too grief-stricken to think clearly about what’s happening, and fails to understand the danger facing him. Luckily, Van Helsing is back in Whitby by this point, and he happens to drop in on Holmwood himself just as the undead Lucy is lining up her fangs over Arthur’s jugular. The bereaved man still doesn’t get it even after Lucy flees, hissing like an enraged cat, from the sight of Van Helsing’s crucifix, but once the sun is safely in the sky, the doctor takes him to see the crypt to which she has returned, just as unmistakably dead as she had been when she was put into it the day before. Now Arthur understands— and credit where credit is due, he manfully bears witness as Van Helsing pounds a sharpened wooden stake through his lover’s unbeating heart. You will recall, however, that Dracula had seen Lucy as considerably more than a midnight snack. When he too visits the Westenra crypt to welcome his new Maria into eternity, and finds her instead dead again for good and all, the vampire acquires a whole new motivation to stay in Whitby. He’s going to figure out who hammered in that stake, and then he’s going to deal with them in the same way he used to deal with the Turks who’d periodically come raiding into his domain back in the 15th century. This, as Roman Moronie would say, is fargin war!

Although Dracula is, as I said, the best remembered of the Dan Curtis horror classics cycle, it’s still a comparatively obscure film today. That makes it all the more remarkable how much influence it has exerted over subsequent adaptations of the story. Bram Stoker’s Dracula in particular owes more to it than to any other prior interpretation. This appears to have been the first Dracula film per se to port over the She-derived reincarnated romance angle that had been a standard feature of mummy movies since 1932— although that trope had figured previously in both Blacula and “Dark Shadows” (and House of Dark Shadows, too, if you feel like counting the movie separately from the TV show). Similarly, this was the first Dracula film I know of to identify the vampire explicitly with Vlad the Impaler. To be sure, Bram Stoker had dropped enough hints in that direction to tip off any reader sufficiently well versed in Medieval history (hell, the title itself is just one letter off from one of Vlad’s nicknames), but Curtis and Matheson do a great deal more than just to hint here.

That being said, it’s worth noting how differently this movie handles the “love across the ages” plot thread from either its successors or its proximate predecessors. Matheson uniquely seems to give the premise almost no in-story credence. That Lucy is Maria reincarnated is something that Dracula believes, but there’s no indication whatsoever that we’re supposed to take his conviction at face value. And because it’s Lucy, and not Mina, on whom Dracula so fixates, his fantasies of post-mortem reunion play no role in the battle for the latter girl’s soul that forms the crux of the movie’s endgame, just as it had the novel’s. Rather, Matheson uses the vampire’s personal investment in Maria’s supposed reincarnation to drive his enmity against Van Helsing and Holmwood, reversing the book’s character dynamics. For Stoker, it was enough that Dracula’s mode of existence made him inherently inimical to humanity. Matheson, master of psychology that he was, gives Dracula a reason to have it in for these humans in particular.

What gets Dracula into trouble, so far as I’m concerned, is Jack Palance. He has his fans in the part, I realize, and I do believe I understand what he was aiming for here. Like the fictionalized Max Schreck says in Shadow of the Vampire, he sought to convey a Dracula so badly out of practice at being human that he’s almost forgotten how to do it at all. In practice, though, Palance just seems painfully awkward and unsociable, with next to no control over his emotions. He’s not so much “undead monster putting on humanity like an ill-fitting mask” as “autism spectrum disorder”— less Count Orlock than Count Asperger. I could see this performance fitting in quite nicely in some screwy-ass thing like Jesus Franco’s Count Dracula or Paul Morrissey’s Blood for Dracula, but here it just thuds against the whole rest of the production, which is all about unobtrusive journeyman competence. However, there is one aspect of Palance’s interpretation that I consider quite canny; I like the way he reacts when people brandish crosses at him. He never seems to be afraid of them exactly. It’s more like they’re too bright for him to bear looking at, and too hot for him to bear getting near. He averts his eyes and keeps his distance, but you can always see him trying to find some way of bypassing the hated symbol to continue his attack. Especially in comparison to how Lucy takes flight when she sees a cross, it’s a good, subtle demonstration of Dracula’s supernatural power. The traditional countermeasures still affect him, but they’re not the surefire defenses that they might be against a lesser vampire.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact