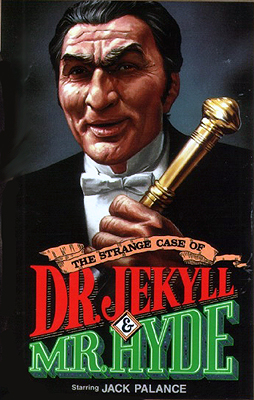

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde (1968) **½

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde (1968) **½

If you look closely at practically any adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, to the big screen, the small screen, or even the stage, you’ll observe that the main load-bearing structure is the dual performance of the actor (or actors, in a few oddball cases) playing the title roles. Other aspects of the production will still matter, of course, but it’s generally safe to assume that any given Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde will be approximately as good as its Jekyll and/or its Hyde. That isn’t true at all, though, of the version produced for American and Canadian television by Dan Curtis in 1968. Although it has at its center two of Jack Palance’s all-time worst performances, just barely preferable to David Hasselhoff’s interpretations of the same characters in the almost indescribably wretched Broadway musical at the turn of the current century, Curtis’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde is, on the whole, quite serviceable. With an intelligent script, energetic pace, inventive and busy video cinematography, some brilliantly chosen shooting locations, and solid to superb performances in all the other roles that matter, it rises far above its alternately inert and flailing star to serve as an encouraging harbinger of what its producer would achieve in the medium of boob-tube horror in the decade to come.

Wasting no time whatsoever, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde begins with Dr. Henry Jekyll (Palance, of Solar Crisis and Craze) attempting, without much success, to deliver a lecture on his theory of duality in the human psyche before a body of his colleagues gathered under the auspices of his friend and mentor, Dr. Lanyon (Leo Genn, from The Bloody Judge and Die Screaming, Marianne). Jekyll’s main trouble is the incessant heckling of Sir John Turnbull (Torin Thatcher, of Jack the Giant Killer and Helen of Troy), who rejects the entire premise of his talk, but gets especially riled up over his contention that a man’s base and virtuous sides might be concentrated and isolated by pharmacological means. And every time Turnbull opens his yap, the assembled worthies of the medical profession transform themselves into a jeering mob of hooligans. Not even the intervention of George Devlin (Denholm Elliot, from The House that Dripped Blood and It’s Not the Size that Counts), Jekyll’s attorney— and thus a representative of a rival intellectual elite, in front of whom the doctors might be expected to be on their best behavior— is enough to shame the audience into dignity or decorum. Well, Jekyll will show them! Although Lanyon assumed that he was speaking purely theoretically, the younger doctor has a drug that he believes will do exactly what he proposed in his lecture, developed with the aid of an extremely shady chemist by the name of Stryker (Oskar Homolka, of The Invisible Woman and Mr. Sardonicus). That very night, Jekyll instructs his butler, Poole (Gillie Fenwick), to turn away all callers, and withdraws into his backyard laboratory to give the concoction its first test on a human subject— himself.

The cleverest thing that The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde does is to refrain from showing us the full results of this first experiment. It cuts to commercial just as Jekyll is doubling over in transformation-induced agony, and then the next thing we see is Poole rousing his bewildered master in his accustomed bed, but long after his accustomed hour of rising. At first the doctor is so disoriented that he doesn’t even remember trying the drug. All Jekyll knows then is that he awakens exhausted, as if he had only just fallen properly asleep after some strenuous all-nighter. He doesn’t begin to suspect what really happened until he finds his lab in uncharacteristically careless disarray, and the cash box in his desk empty but for an IOU for £65 that’s almost in his own handwriting. Jekyll finds another curious clue in the pocket of his topcoat, a flyer advertising a performance of “Tessie O’Toole and her Soldier Girls” at a Soho music hall and whorehouse (and Dutch pancake house, too, if the architecture is any indication) called the Windmill. The strangest and most illuminating clues are those that confront the doctor at the Windmill itself, where the proprietress— the aforementioned Tessie O’Toole (Tessie O’Shea)— and several of the staff prostitutes deny recognizing Jekyll, but remark that they were visited last night by a different gentleman (the establishment doesn’t normally get much trade from that sort, you understand), a boisterous, free-spending fellow who called himself Edward Hyde. Now Jekyll understands what happened. Despite remembering no such thing even now, he must indeed have tried his personality-separating potion last night. And since the first thing his alter-ego did was to spend a small fortune carousing at a bawdy house, it probably wasn’t the doctor’s purified good side that emerged, regardless of his intentions.

From standpoints of 1968 and later, however, we might justly ask how bad Jekyll’s liberated bad side could really have been if the most nefarious thing he got up to was to show everybody at the Windmill, employees and customers alike, a rollicking good time. The doctor never articulates that thought himself, naturally, but something like it is almost certainly on his mind when he summons Stryker to his home in order to buy a job lot of the ingredients for his drug, and when he begins blowing off all his painfully upstanding old friends in order to dedicate as much time and energy as possible to the experiment of his new double life. Meanwhile, it seems equally likely that Jekyll feels rather cheated by the lacuna in his memory, and that he hopes to remember getting drunk as hell and laid as fuck after adopting the persona of Hyde in the future. Well, the good news is, Jekyll will have ever-stronger memories of Hyde’s activities going forward, as his brain adjusts to the novel experience of toggling between personalities. The bad news is that the more frequently Hyde comes out, the worse he behaves, and the less Jekyll will want to remember what his second self has done.

For example, there was one man at the Windmill that first night who didn’t find Hyde’s antics charming at all. The fellow’s name is Garvis (Donald Webster), and he’s a regular client of a hooker called Gwyn (Billie Whitelaw, from Frenzy and The Flesh and the Fiends)— so regular, in fact, that he’s come to think of himself as the girl’s beau. Garvis took it very badly indeed when he saw how much Gwyn was enjoying Hyde’s company, and he’s determined to give that rich lecher a piece of his mind the next time their paths cross. It’s just Garvis’s rotten luck that said crossing of paths occurs mere hours after Hyde has taken delivery on the lead-handled sword cane that he ordered from a vendor in Paris during one of his early manifestations. It’s rather disturbing for Jekyll to recall what Hyde did to Garvis and his buddies, although he can at least tell himself that they got only what was coming to them. (Well, maybe just a bit more…) He’ll have a much harder time inventing justifications for Hyde’s treatment of Gwyn after Garvis is out of the picture, though. After all, it’s one thing to discover upon awakening that his alter ego clobbered a pack of ruffians in a four-on-one street fight, but something else again to acquire secondhand memories of whipping a defenseless girl bloody with a rattan cane. The breaking point for Jekyll, though, is what Hyde does to Lanyon when the old doctor objects to Hyde appropriating his carriage one night after an evening out with another pair of whores. Like everyone else to provoke Hyde’s wrath so far, Lanyon survives the experience, but it’s a narrow thing indeed in his case.

Jekyll’s determination to get back to himself faces several obstacles, however. Hyde’s activities have won him infamy even among the infamous, and his reputation in turn has drawn the attention of London municipal vice cop Sergeant Grimes (Duncan Lamont, of Five Million Years to Earth and Nothing But the Night). Naturally, Grimes can’t help but wonder why Hyde keeps being spotted near the home of Dr. Henry Jekyll, why Jekyll recently instructed his solicitor to open a bank account in Hyde’s name to receive regular transfers of funds from his own account, and whether it’s merely a coincidence that the victim in Hyde’s most serious crime to date was one of the doctor’s estranged friends. George Devlin, meanwhile, is asking many of the same questions from the opposite direction, and he’s especially concerned when Jekyll has him draw up a new will naming Edward Hyde as his principal heir. The doctor is able to parry some of those questions by identifying Hyde as a paid research subject, but doing so raises further, equally inconvenient questions in turn. Gwyn starts nosing around Jekyll, too, after his conscience demands that he pay her a visit, tend to her latest set of abuse injuries free of charge, and arrange for her to receive a regular stipend. Jekyll might claim that the subsidy comes from Hyde, who he says has gone abroad to the Orient, but Gwyn’s been in her business too long not to recognize payoff and/or hush money when she receives it, and neither one of those things strikes her as Hyde’s style. Then there’s Stryker, the one man familiar enough with Jekyll’s work to guess at its purpose, observant enough to spot even from afar the signs of its success, and crooked enough to exploit what two and two add up to here. But naturally the gravest obstacle is Hyde himself, who by the time of Jekyll’s epiphany has begun to influence the doctor’s personality and outlook even when he’s himself, and who has now grown strong enough to emerge from his respectable alter ego even without pharmacological assistance.

I really cannot overstate how atrocious Jack Palance is as both Jekyll and Hyde. His stiff, stuffy, awkward, and overly mannered rendition of the doctor might be marginally defensible if The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde were aiming for the kind of introverted, ineffectual Jekyll that Paul Massie and Anthony Andrews played eight years earlier and twenty years later respectively, but this movie is trying for a brash scientific renegade on the Fredric March model instead. It’s impossible to imagine Palance’s Jekyll having the cojones to engage Sir John Turnbull in a lecture hall sparring match— or indeed to present in public an idea that might provoke Turnbull to such rhetorical combat in the first place. Palance does a little better in the film’s midsection, as Jekyll begins to take on a few of Hyde’s characteristics, but even that improvement is counterproductive in context, because the more assertive, sharper-tongued, convention-flouting Jekyll that Hyde brings out is not merely altogether more attractive a personality than the baseline version, but also much closer to what the baseline Jekyll needed to be for this take on the story to work as well as it should. Palance thus gives us the worst kind of Jekyll, the sort that needs the bad influence of Hyde to become credible as someone who would ever have conceived the experiment that created him!

Nor is Palance’s Hyde much better. As with Jekyll, he does manage a laudable moment here and there, like when Hyde romances Gwyn early on, or when he finishes settling his accounts with Garvis, but if you’ve ever seen Palance play a villain in a European exploitation movie— Deadly Sanctuary, Hawk the Slayer, and Outlaw of Gor all spring to mind— you’ll have some idea what to expect. Although there is some virtue to the notion of playing Hyde as simply the opposite of whatever Jekyll is, such an interpretation is starkly at odds with this movie’s philosophical concerns, which we’ll discuss shortly. And even if it weren’t, Palance takes “the opposite of Jekyll” to mean little more than a lot of frenzied gesticulation and leaping about, or bellowing at a volume that deprives him of any ability to maintain a natural vocal cadence. His acting is so blunt and crude that it even defeats the most interesting implications of Dick Smith’s unique (albeit not very well executed) makeup design, modeled after Roman-era depictions of satyrs.

Fortunately, everything else about The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde is good enough to make the picture well worth watching in spite of Palance (except for Torin Thatcher, who absolutely belongs in the same movie as the star). The crucial factor is that screenwriter Ian McLellan Hunter has a clear perspective on where the evil in this story lies, and keeps that perspective squarely in his sights at all times. Despite what Jekyll himself might think, this is no tale of the duality of man. Hunter, following John Lee Mahin, treats it instead as one about the seductiveness of wrongdoing. What begins with the thrill of harmless norm-breaking quickly escalates into the much darker exhilaration of deliberate, wanton cruelty against ever less deserving targets. Edward Hyde, in other words, is not the villain here. His existence, rather, is an act of villainy that Jekyll commits— unwittingly at first, to be sure, but with more and more indefensible premeditation each subsequent time he imbibes the drug that sets Hyde free. And in the end, it isn’t merely a matter of chemical tolerance that prevents Jekyll from maintaining his own identity; Hyde is quite simply what Jekyll has become by that point, and has been without recognizing it for some time. It’s appropriate, then, that the climax should unfold as a confrontation between Hyde and George Devlin, who had tried to be the truest and most difficult sort of friend to Jekyll. Whereas most other adaptations treat the analogous figure (usually called “Utterson”) as a starchy avatar of mere propriety, this one roots Devlin’s efforts to pull Jekyll back from the brink in genuine concern for the doctor’s safety, sanity, and well-being, and in the conviction that friends don’t let friends devolve into monsters.

In a similar way, it’s significant that The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde eschews the tradition of parallel love interests for the title characters. This version has only the “bad” girl, who falls for Hyde when he’s just a charismatic rake, and comes to regret it as he matures into a brutal sadist. Notice, too, that although Hunter retains from the 1931 and 1941 films the plot twist in which Gwyn (called “Ivy” back then) throws herself at Jekyll during his attempt to reform by renouncing the transformation drug, it means something different here, without the earlier incident in which Jekyll, passing through Soho one night, rescues her from a would-be rapist. The Ivies each have reason to build Jekyll up in their minds as a contrast to the sordid males they’re accustomed to dealing with, but Gwyn initially knows the doctor only as a man who would claim friendship with quite possibly the world’s worst son of a bitch. That introduces an intriguing hint of ambiguity to Gwyn’s pursuit of Jekyll. Howeer benignly she frames her interest in him, there’s always just the faintest whiff of blackmail to their interactions— and it’s hard to argue that Jekyll wouldn’t totally deserve it if indeed that were what she had in mind. Billie Whitelaw is terrific during this phase of the film, too, particularly since Gwyn has been nothing but an innocent victim up to then.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde is also extraordinarily well handled on a technical level, and what’s especially interesting there is that it seems to have been a case where one really good decision essentially forced a whole cascade of others. Most shot-on-video TV movies of this era were taped in studio facilities, whether on soundstages or on backlots. 60’s-vintage videotape was extremely finicky about lighting, so the more controllable the shooting environment, the better. It would have cost a fortune to build from scratch the simulacrum of Victorian London that this film required, however, and the Canadian tax incentives Curtis was relying on required the actual production to be mounted in-country, far away from the decades’ worth of standing sets scattered all over Hollywood that served the needs of so many other mid-century period pieces. Luckily, Toronto had in its old distillery district the largest concentration of Victorian-era commercial buildings in all of North America— and in the late 1960’s, the area was in a state of Rust Belt-like economic free fall. The landlords were more than happy to give a TV crew armed with international coproduction money the run of the place after hours, with the result that The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde has the most eye-catchingly authentic 19th-century urban settings you’ll see just about anywhere. But because the streets and buildings were what they were, built without reference to the needs of movie or TV production, taping in the distillery district also meant that director Charles Jarrott and his cameramen had to work around and exploit whatever oddball lines of sight and lighting configurations presented themselves, rather than following the standard playbook of television shooting practices. The environment left them no choice but to be ingenious. It left them no choice but to show kinds of scenery that they would never have thought to ask for. It left them no choice but to light that scenery in unusual ways, and to record it from unusual points of view. It left them no choice but to scramble around those pain-in-the-ass sets with hand-held cameras, forsaking coverage, and making every shot count. In short, it left them no choice but to make The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde the kind of risk-taking, expectation-defying project that one rarely saw among 1960’s telefilms.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact