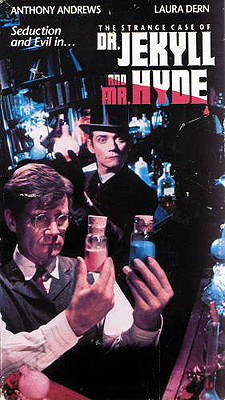

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1989) ****

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1989) ****

If you had asked me last week what was the best Jekyll-and-Hyde film, I’d have told you it was too close to call between the Paramount Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde with Fredric March in the title roles and the MGM remake from ten years later featuring Spencer Tracy. Then I’d have identified The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll as the best revisionist version, and mumbled something about honorable mention for I, Monster. That was last week, though. This past weekend, I got reacquainted with an adaptation of the story that I’d forgotten about almost completely, the hour-long TV movie produced for Showtime in 1989 as part of Shelly Duvall’s “Nightmare Classics” package. It’s shockingly good. What’s more, it so deftly weaves together material from so broad a selection of previous interpretations that I’m honestly not sure whether to characterize it as a revisionist take or a traditional one. What I do know for certain is that screenwriter J. Michael Straczynski and star Anthony Andrews between them have solved the most intractable problems which this story presents, and that director Michael Lindsay-Hogg achieved an admirable balance of artistry and efficiency on a budget that would have just about covered an ordinary movie’s dry-cleaning bill in 1989.

As always, the first question is, what sort of man is Dr. Henry Jekyll (Andrews, from Haunted and It’s Not the Size that Counts) going to be this time? Straczynski goes for a social-reform crusader on the John Barrymore model, but interestingly makes him also a pathologically timid introvert like Paul Massie’s Jekyll. Nevertheless, he’s been drawn far enough out of his shell on this occasion to attend a party with his friend and assistant, Richard Utterson (Wishcraft’s Gregory Cooke). I can practically hear the pitch Utterson must have made. For one thing, the host is Professor Laymon (George Murdock, of Willie Dynamite and A Howling in the Woods), Jekyll’s boss at the medical college where he teaches, so attending the party is good politics. And for another, it’s a foregone conclusion that Laymon’s daughter, Rebecca (Laura Dern, from Jurassic Park and Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains), will be there, and any fool can see that she’s infatuated with Jekyll. Jekyll has a thing for her, too, so this party could be his chance to close the deal. Alas, though, Henry’s conversation with Rebecca is intruded on just as it’s getting properly started by Dr. Frederick Morley (Nicholas Guest, of Nemesis and Puppet Master 5), the Bluto to Jekyll’s Popeye. Jekyll gets tongue-tied in the face of Morley’s taunting, and flees the party for the safety of his lab. On way home, he finds himself peeping with a mixture of longing and distaste at a prostitute and her john pawing each other like savages in an alley.

Now when I said before that Jekyll was a social-reform crusader, I didn’t mean temperance campaigns, good-government initiatives, investment in infrastructure for public hygiene, or anything obvious like that. No, Jekyll hopes to reform society at the source, by perfecting the human brain. After all, the brain is ultimately just another organ, right? So doesn’t it stand to reason that the brain’s physical health could find reflection in human behavior? And if that’s true, then doesn’t it follow that surgical or pharmacological interventions could correct the derangements of the brain that manifest themselves in the behavioral patterns that we call evil? The trouble is, Jekyll is so taken with the concept the he keeps running off at the mouth about it, even when he’s supposed to be teaching medical students about the other, better understood parts of the human organism. People are starting to notice— people like the stuffy old duffers on the college’s board of regents— and Laymon is getting tired of defending Jekyll to them. One afternoon, after watching Jekyll fill the heads of yet another anatomy class with wild speculations, Laymon tells the younger doctor in no uncertain terms that he has to let this mind-reform business go unless and until he can furnish positive proof of the idea’s validity.

That intervention from Laymon is what it takes to spur Jekyll to action at last. He’s believed for some time now that he has the proof his boss requires, in the form of a drug that he’s been developing with Utterson’s help. Experiments on animal subjects have been consistently promising so far, although Jekyll doesn’t specify what that might mean exactly. He has yet to try it on a human, however, even though he also possesses a second drug proven to counteract the first. After all, a man is not a rat, and what Jekyll proposes to do is so drastic that he believes it would be unethical for him to test his virtue-concentrating compound on anybody but himself. Up until now, he was afraid to do so, but Laymon’s ultimatum has steeled him at last. That very night, Jekyll shuts himself up in the lab and imbibes the potion that is supposed to unify and perfect his psyche.

It… kind of works? The being who remains once Jekyll’s nostrum has done its work unquestionably is a singularly pure and unconflicted specimen of humanity. Unfortunately that’s because Edward Hyde (as Jekyll’s alter ego dubs himself) is totally devoid of conscience, empathy, or capacity for remorse. He’s perfect, alright, but he’s a perfect sociopath. Hyde isn’t fond of Jekyll, or of the way he’s hitherto lived, either, and the first thing he does is to go out on the town to live very differently indeed. His first stop is a tavern, where he befriends Richard Utterson (and finances him on a piss-up for the ages), picks a fight with Fred Morley (which ends with the smug bully humiliated in spectacular fashion), and romances Morley’s date in the defeated man’s stead.

Jekyll is mortified when he returns to himself in the morning. How could he have been so completely wrong? But then a visit from Utterson gives him something else to think about. Far from being appalled by Hyde’s behavior, Utterson was charmed by his fearless disregard for propriety, convention, or social expectations of any kind. So what if the problem with Hyde is really a problem with Jekyll? What if, for all his free thinking in the realm of science, the doctor is as hidebound and conservative as the board of regents where mores and values are concerned? The only way to find out, or so Jekyll figures, is to become Hyde once again, and to make a point this time of looking past “the rules” to evaluate him as dispassionately as possible. While he’s working up the nerve to do that, Rebecca comes by to invite him to a charity fundraising event at her father’s house— one which she strongly implies Morley will not be attending. His attention riveted elsewhere, poor Henry makes a complete ass of himself.

Hyde’s second outing erases any possible doubt as to his nature. This time he visits a whorehouse, where he and the madam (Rue McLanahan, of Starship Troopers) have a tense moment over the availability of a virgin whom she has been holding in reserve for just the right customer. In the end, Hyde contents himself with an ordinary ménage-a-trois, but leaves no doubt that he intends to return and reopen the question another day. After that, he takes one of the girls out for a walk, and gives her quite an earful— ranting about some tedious schmuck named Jekyll, attempting to goad her into stealing a dress from a storefront, and boasting grandly of his own ability to commit any crime in the book without fear of getting caught— before dragging her into the very same alley where his other self perved on a similar assignation a few nights before. The evening goes absolutely haywire, though, when Hyde returns home and sees the invitation from Rebecca. Rather than quaffing the antidote as he originally intended (“Wouldn’t want the neighbors to start talking…”), Hyde sets out again, bound for the Laymon house— and never you mind that it’s three in the morning or whatever. Laymon himself is naturally not pleased with this unknown guest who arrives long after the party is over, but gets nothing for his efforts to send Hyde packing but a thorough walloping with the intruder’s cane. Hyde gives some thought to raping Rebecca too while he’s at it, but decides in the end that he’s lingered too long as it is. The servants have no doubt summoned the police, and it wouldn’t do to be arrested. Time for Hyde to avail himself of that ultimate refuge he told the whore about, and to disappear back into Jekyll. Henry, obviously, has a real problem now— or rather, he has two real problems. The first, of course, is how to live with the knowledge of what Hyde has done. But the other is arguably even worse. Having experienced so fully the liberation of evil, Jekyll now finds himself too weak to deny his desire for more.

It amazes me that it took 100 years for an adaptor of this story to devise so elegant a solution to the problem of Jekyll’s motivation. Or then again, maybe one of Straczynski’s predecessors did think of it, but recoiled from the implications. Edward Hyde is a mistake here, an unwelcome surprise suggesting a fundamental error in the thinking behind Jekyll’s research. The doctor assumed that to distill man’s deepest essence would be to create a being of ultimate compassion, ultimate reason, ultimate virtue. The outcome of his experiment points instead toward the conclusion that the core characteristic of humanity is a spiteful, brutal, hateful, grasping selfishness that revels in the suffering of others. The best that can be hoped for is that these findings cannot be generalized— that Hyde reveals the secret self of Jekyll and Jekyll alone. But if a personality so monstrous can lurk at the center of a psyche so outwardly decent and gentle, then I wouldn’t put much stock in that hope. Straczynski’s explanation for how and why Hyde came to exist makes this easily the darkest, most pessimistic version of the Jekyll-and-Hyde story that I’ve ever encountered, and also the most unsettling. Because although I personally incline toward a more sanguine view of human potential, I can’t confidently assert that Straczynski is wrong. “Nightmare Classic” indeed!

The other persistent difficulty with this story is how to differentiate the two title characters sufficiently that people who know one can’t recognize the other— especially if just burying Hyde under monster makeup isn’t an option . The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde uses by far the subtlest transformation makeup I’ve seen yet. Hyde’s complexion is a shade paler than Jekyll’s, he doesn’t wear glasses, and he slicks his hair back instead of letting it flop shapelessly atop his head. Everything else distinguishing the evil alter ego from the good one is a matter of acting: different posture and carriage, different manners of speaking, different body language, and most of all different use of the eyes. Jekyll never makes eye contact with anyone if he can avoid it. Hyde, on the other hand, begins practically every interaction by staring the other person down. And yet the two characters really are just barely recognizable as the same man. By way of contrast, Spencer Tracy, Christopher Lee, and Anthony Perkins (to pick three Hydes from the minimally monstrous end of the spectrum) each wore considerably more makeup, but none was ever quite believably disguised. Here, though, it’s enough to have Utterson ask Hyde if they haven’t perhaps met before during that first night at the tavern. Hyde’s “Hardly” puts the issue of recognition to rest.

So what is Andrews doing so differently? The quickest way to describe his Jekyll is to say that he is exactly Anthony Stewart Head’s later and more famous portrayal of Rupert Giles in the first season of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” before the latter character acquired the dark undercurrent that made him so interesting. The Andrews Jekyll is stuffy, fussy, easily flustered, and fully at ease only when lecturing on the subject of his work. Andrews’s Hyde, on the other hand, is equal parts Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange and the unnamed MC from Bob Fosse’s Cabaret. He swaggers and looms, seeming (as Utterson astutely puts it) to take up more room than other people despite his utterly unremarkable physical stature. And he wields the cane with which he eventually pummels Dr. Laymon as if it were an extension of his own body, using it as much to gesture and intimidate as to secure his footing on the uneven London cobblestones. Even so, most of Hyde’s mannerisms are traceable somehow to Jekyll’s, like the way Hyde’s brittle aversion to being touched seems to echo Jekyll’s fastidiousness about his person and belongings. Overall, it’s as masterful an assay of a dual role as any I’ve seen.

One last thing that I feel honor-bound to comment on is how good The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde looks, despite having been made for cable TV at the turn of the 90’s, when made-for-cable was an even lower stratum of the cinematic ecosystem than direct-to-video. The period sets and costumes never look cheap, nor do they show any obvious signs of having been repurposed from another, better-funded production. Although it was shot on videotape, it mostly escapes the dull, characterless appearance typical of its era’s video cinematography. And it’s clear throughout that Michael Lindsay-Hogg never took the cramped shooting schedule as an excuse to forego the setup necessary to capture an attractive or visually interesting image. The only place where the lack of resources begins to show is the score, in which the production tried to cheat the cost of an orchestra by using synthesizers to simulate a few too many of the background instruments. There’s no problem so long as it’s just a solo violin, cello, or piano on the soundtrack, but the fuller the arrangement becomes, the cheesier the music sounds. Still, as weaknesses go, that’s pretty forgivable.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact