Willie Dynamite (1973) ***

Willie Dynamite (1973) ***

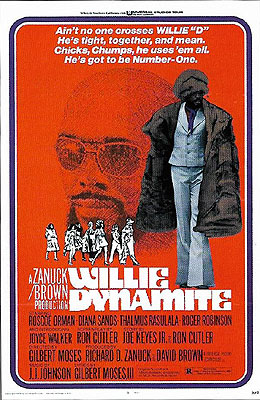

Watching Willie Dynamite, I realized that I’ve evolved a sort of informal system for setting my expectations of a given blaxploitation movie. The tackier and more preposterous the clothes, the campier and sillier the film is likely to be. In general, it’s a sound rule, and I’m not surprised that my subconscious settled on it. It doesn’t always work, though, and as you might guess from the fact that Willie Dynamite provided the impetus moving the rule from my subconscious mind into my conscious one, this is one of those times when it led me astray. When the title character made his entrance looking like a giant, ambulatory strawberry Zinger, decked out in a hot pink suit, hat, and overcoat sprinkled with strips of white fur, I figured I had this movie’s number. But by the start of the second act, it was becoming increasingly apparent that Willie Dynamite fell closer to Superfly’s end of the spectrum than Avenging Disco Godfather’s. Despite outward appearances to the contrary, it develops into a fairly serious examination of life in the black criminal underworld of 1970’s New York. And also like Superfly, Willie Dynamite is unusually generous with its sympathies, having enough to go round for pimps, prostitutes, social workers, law-enforcement personnel, and all the people caught in the crossfire of a city descending into outlawry.

The Willie Dynamite of the title (Roscoe Orman, best remembered as Gordon on “Sesame Street”) is an ambitious smallish-time pimp, one of several loosely confederated under the leadership of a more powerful black crime boss named Bell (Meteor’s Roger Robinson). Willie and his right-hand woman, Honey (Norma Donaldson, from Across 110th Street and The Unholy), have his stable of seven whores running at military efficiency for the most part, but the newest recruit (Joyce Walker, of Shaft’s Big Score and Howling II) is proving troublesome. As the youngest and by far the most beautiful of Willie’s girls, Pashen— pronounced like “passion”— ought to be an economic powerhouse, commanding high rates, quick turnaround, and strong customer loyalty. Instead, though, she’s the least productive of the bunch, bringing in barely enough to cover her overhead in clothes and cocaine. As you might surmise on that basis, Pashen is having second thoughts about her place in the Oldest Profession, although she isn’t prepared as yet to admit that even to herself.

Even so, underperforming hookers are just one of Willie’s worries right now. While Honey and the rest of the girls work the hotel hosting a Shriners convention, Bell calls a meeting of his associates. The boss is sure he’s not the only one to notice the recent stark increase in police activity directed against the prostitution trade, and his sources for NYPD scuttlebutt give him reason to suppose that the cops aren’t going to be slacking off anytime soon. More heat from the police means more resources wasted on bail and lawyers, a shrinking playing field where hookers can operate safely, and downward pressure on prices as the threat of getting busted scares away the more skittish segments of the customer base. If the crackdown goes on long enough, the hitherto amicable competition among Bell’s followers is apt to turn ugly and violent, which will be even worse for business. The way Bell sees it, there’s just one workable strategy for riding out the coming tough times; his organization is going to have to get more rigidly organized. Under his proposed new scheme, each pimp will get his own exclusive territory. That way, nobody has to worry about his partners crowding him when the cops get too busy on their turf, and the police are forced to play Whack-a-Mole as each pimp whose zone comes under their scrutiny lies low in turn. Also, exclusivity will make it easier to squeeze out freelance streetwalkers, since no one will have to worry about an unfamiliar girl belonging to one of his fellows. Five of Bell’s compatriots— Baylor (Robert DoQui, from Coffy and Guyana: Cult of the Damned), Top (Jac Emil, of The Student Nurses and Truck Turner), Cyrus (Ron Henriquez), Sugar (Nathaniel Taylor, from Trouble Man and Black Girl), and Milky Way (some white guy who didn’t get his name in the credits)— agree with his reasoning, but not Willie. Willie Dynamite likes competition, and the sharper it is, the better he likes it. “I thought we were all capitalists,” he disgustedly says in response to Bell’s proposal. Now Bell is a forgiving sort as crime lords go, so this show of insubordination doesn’t immediately result in Willie getting whacked. You can bet, though, that he’ll be hearing from the boss again if the cops drive the screws in any tighter, and that next time, Bell won’t be so willing to take no for an answer.

There’s more bad news waiting for Willie when he comes home from the meeting, too. Pashen just got herself arrested, and the pimp’s ability to do anything about it is impeded by the fact that his car has been towed away. Meanwhile, there’s a more serious complication brewing out of Willie’s sight. District Attorney Robert Daniels (Thalmus Rasulala, from Blacula and Friday Foster) has a girlfriend by the name of Cora Williams (Diana Sands), and Cora is on a crusade to get hookers out of “the life.” She used to turn tricks herself before she became a social worker, and she did as much smack in her time as all five of the New York Dolls. In other words, she knows what it’s really like out there on the street, and her background gives her a credibility that more conventional social workers can’t match. When Cora sees Pashen in that holding cell, young enough not to be set in her ways yet and pretty enough to take advantage of the modeling industry contacts that Williams has cultivated for just such purposes, she figures she’s found a promising target. It isn’t just Pashen that Cora sets her sights on, either. She used to do her hooking on a freelance basis, so there’s nothing she hates more than a pimp. As soon as she figures out whom Pashen is beholden to, Cora starts making herself a regular uninvited guest at the apartment that Willie rents to house his stable. This was where I realized that I had underestimated Willie Dynamite. I mean, how many blaxploitation movies can you think of in which somebody starts hanging around a whorehouse, fomenting labor unrest like a 1920’s union organizer?!

Willie gets unlucky once again with the particular cops the department puts on the case developing against him. The older of the two partners, Celli (George Murdoch, from Thomasine and Bushrod and A Howling in the Woods), is an old school New York Italian lawman— which is to say that he’s racist as fuck, and that he harbors a special loathing for perps like Willie who have the temerity to educate themselves on the finer points of the state criminal code. The younger cop, Pointer (Cotton Comes to Harlem’s Albert Hall), is a black nationalist, meaning that he has a special loathing for people who reinforce white stereotypes about Negro criminality by living down to them. With these two on the job of bringing Willie down, he’ll be getting it coming and going.

This isn’t anything half as simple as the “rise and fall of a gangster” story it’s starting to look like, though, because we’re about to meet Willie’s family. He’s got a mother, a sister, an aunt, and an uncle, before whom he’s been posing all this time as a record producer. Mom (Royce Wallace, of Cool Breeze) suspects the truth about how he earns his living, however, and rather masterfully makes her disapproval known without ever having to address the embarrassing issue directly. When Willie’s inevitable slide toward the abyss begins in earnest, the hardships fall hardest on these innocent bystanders— hard enough, in fact, to make Cora want to attempt the seemingly impossible, and drag Willie out of the criminal lifestyle along with his whores.

Since I started this review by saying that I had been led astray in my expectations of Willie Dynamite by its amazing sartorial vulgarity, and because that sort of thing always accounts for a bit of the fun in even the most staid and sober blaxploitation movies, I suppose I own you all a few details on the subject. Willie’s opening impersonation of a mass-produced snack cake sets the pattern for virtually his every appearance, for in all but a handful of scenes, he appears to be cosplaying as somebody’s dessert. First he’s a strawberry Zinger; then he’s a key lime pie; then he’s an Arabian-themed wedding cake; then he’s a bag of Hanukah gelt. Even his more muted outfits are hideous, like the camel-brown jumpsuit he wears to Sunday dinner with his family, which he might have bought from a “Space 1999” garage sale were it not for the chest-baring, waist-deep V-front and a gargantuan, square collar that appears to be made of tuck-and-roll automotive upholstery. And believe it or not, Willie’s wardrobe is not the most uncouth in the film. That honor belongs to Bell, who comes across as nothing less than a black Liberace— although even Mr. Showmanship himself might have balked at those inch-long gilded fingernail extensions. You’ll have plenty of opportunity to marvel over Bell’s fake fingernails, too, because he gesticulates so emphatically whenever he talks that you could almost mistake him for his own American Sign Language interpreter.

But enough about what Willie Dynamite looks like; let’s get back to talking about what it is. As I said, it first dawned on me that I had misjudged this movie when Cora Williams started chasing after Pashen in earnest, but just as importantly, that’s also when I realized that I was no longer sure who the protagonist was. Was this indeed going to be the story of a pimp’s rise and fall (or triumph over adversity, or redemption, or whatever)? Or was it actually the tale of a naïve young hooker’s forceful education and escape from the sex trade? For that matter, might it even be about a junkie whore turned no-nonsense social worker struggling to pound some of her hard-earned wisdom into the heads of young girls still in the life? Remarkably, Willie Dynamite turns out to be all those things, including arguably all three of the seemingly incompatible possibilities I suggested for a Willie-centric through-line.

Pashen’s story is the most tragic, although even it stops short of the full 70’s bummer. As Cora continues to lean on her, she slowly admits to herself that she’d rather be a fashion model than a sex worker after all, which naturally leads to friction between her and her pimp. Pashen never actually stops hooking, though, and the next time she gets busted, Willie is unable to bail her out because of his own legal difficulties. She ends up staying in jail until Cora comes to rescue her, and by that point, things have already gone very badly. It plays out almost like one of those scolding vice-exploitation movies from the 1930’s, the key point being that Pashen is the closest thing Willie Dynamite has to a naïve innocent. The old vice pictures almost always saved their worst abuses for such characters, because doing so both catered to the prejudices of the rural roadshow audience and made it easier to dodge censorship trouble by asserting the film’s didactic value: “No, sir— we’re not reveling in dissipation and immorality at all. We’re issuing a stern warning of what happens to good kids who fall in with bad crowds!” Willie Dynamite wasn’t made in the 30’s, though, and such moralistic sleight of hand had long been unnecessary by 1973. If writer Ron Cutler and director Gilbert Moses didn’t need to give this movie a conventional morality play aspect, then it must have been something they wanted to do. The reason why, I suspect, is that it fit in with the film’s broader thematic project of examining from every angle the rising power of criminal enterprises in urban black communities. What The Cocaine Fiends and Marihuana: The Weed with Roots in Hell played for simple exploitation value, Willie Dynamite bends to a more thoughtful and intelligent purpose.

Think about who Willie’s enemies are, and I believe you’ll see what I mean. The racist white power structure is represented only by Detective Celli, but the war of humiliating irritations that he and his partner wage against the pimp will be plenty evocative enough for anybody who ever ran afoul of present-day New York’s stop-and-frisk initiative. Nor, I think, will it be just black viewers for whom the continual legal harassment makes Willie look temporarily a little more sympathetic whenever it’s going on. After all, who these days except the very rich and the very well-connected hasn’t had some run-in with uniformed bullies or revenue-raising shakedowns by municipal and county-level authority figures? Significantly, however, Willie faces the strongest animosity from his black foes, because they, unlike the bigoted Celli, genuinely expect better from him. To his mother, Willie is a personal disappointment, a disgrace to the family honor, and a reproach to her own abilities as a parent. To Cora, he’s an exploiter and abuser of women, and an economic parasite. To Bell and District Attorney Daniels alike, he’s a threat to the orderly functioning of the city (although those two men obviously have very different understandings of what that means). And to Pointer, he’s nothing less than a race traitor. It’s a pretty nuanced list of reason why pimps suck, and a very interesting one to see laid out alongside both Pashen’s alarmist 30’s-style downfall and the forthright admission that the NYPD is a haven for unreconstructed racism.

But what’s more interesting still is that Willie Dynamite gives its title character a fair chance to speak up for himself, and to give his own interpretation of the story. The way Willie sees it, he’s doing nothing but chasing that American Dream people are always talking about. He’s got a product people want and a successful business model for giving it to them. The way he treats his staff is no different from what goes on in any company where the boss keeps an eagle eye on the bottom line. And like he tells Bell at that meeting, he’s all about the free market. So why the hell can’t he just practice his trade and get comfortably rich like any other shrewd and effective businessman? Willie never really changes his mind about the basics of that, either. To the extent that the ambiguous ending hints at his nascent reformation, it’s simply a question of him deciding that the sex trade has too much bullshit baggage attached to it, and that pimping doesn’t seem to be worth his while anymore. Still, there’s a strange kind of optimism in that. Willie’s going to land on his feet, however far he might have to fall first, and maybe— just maybe— the man he becomes after his next self-reinvention will be somebody whom the people who stood in his way this time can get behind.

As long as we’ve been doing this, it continues to surprise me how much cult-cinema territory remains where the B-Masters have yet to venture as a group. This month, we address one of the really glaring omissions with a roundtable devoted to blaxploitation movies.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact