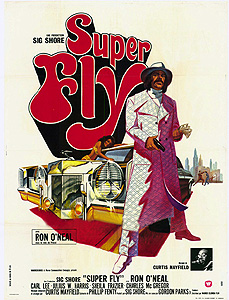

Superfly (1972) ****

Superfly (1972) ****

The year after Gordon Parks showed that an action movie aimed primarily at a black audience could become a mammoth crossover hit and even get nominated for major industry awards, his son, Gordon Parks Jr., turned blaxploitation into a family business. Parks Jr.’s debut feature, Superfly, is nearly the equal of his father’s Shaft, and shows that the younger director was paying close attention to his old man, but it is a strikingly different movie in terms of tone and perspective. Though the title character in Shaft operated mostly outside the law, he was nevertheless its ally, and could be counted without reservation as one of the good guys. Superfly’s central figure, on the other hand, is a much shadier character, a supremely successful Harlem cocaine dealer who wants to quit while he’s ahead, but whose very success in the dope-pushing business guarantees that some very powerful and very dangerous people don’t want to let him take early retirement. He is among the most anti of all the blaxploitation antiheroes, and he gives Superfly more seriousness and complexity than any other such film I’ve seen, with the possible exception of the only slightly less brilliant Black Caesar.

We begin with a pair of junkies (Make Bray and James G. Richardson, of Meteor) who have come to the conclusion that they lack the funds necessary to procure their afternoon fix. Obviously the only thing for it is to steal the money from somebody else, and with so little cash trickling through the hardened arteries of Harlem’s legitimate economy, the junkies figure their best bet is to rob somebody involved in the drug trade. Enter the flamboyant gentleman known as Priest (Ron O’Neal, from The Master Gunfighter and When a Stranger Calls). He heads up one of the neighborhood’s biggest and most lucrative coke rings, and one of the junkies has learned that he’s supposed to be making a pickup that very day. The two addicts ambush Priest in the front hall of the crumbling tenement house where he was intending to make his deal, and one of them manages to run off with an immense wad of cash. He doesn’t quite run fast enough, however, and after a long and hectic chase through the alleys of Harlem, Priest catches up to the fleeing junkie in the living room of a stranger’s flat, kicks the crap out of him in front of the apartment’s astonished tenants, and reclaims the stolen money.

It’s all in a day’s work for Priest, and for precisely that reason, he’s beginning to grow weary of the life he and his partner, Eddie (Carl Lee, of Gordon’s War and Werewolves on Wheels), have made for themselves. He also isn’t fond of the necessity for disciplining the dealers who work for him, as when he orders Fat Freddie (Three the Hard Way’s Charles McGregor) to make up for gambling away his past month’s pushing revenues by serving as the gunman in an anti-mafia holdup down in New Jersey. (Violence and firearms, you see, are normally against Fat Freddie’s principles.) Of course, as Eddie points out to him, Priest isn’t really in a position to just walk away from the criminal lifestyle. Between them, he and Eddie have managed to sock away about $300,000, but Priest is as big a user as he is a dealer, and his share of the haul will be “just about enough to keep [his] nose open for a year.” Meanwhile, it isn’t as though Priest has exactly been studying up for a career change— as he himself will admit later, his criminal record by itself is enough to bar him from all but the most menial legitimate employment. No, if Priest is going to break away from his life in the underworld, he’s going to have to pull one last spectacular deal, then cut and run before the windfall has had a chance to vanish up his nose. Priest is a resourceful guy, though, and he already has just such a plan. You see, he isn’t the only coke pusher in Harlem looking to go out of business just now. There’s an old man named Scatter (Julius Harris, from Friday Foster and Maniac Cop 3: Badge of Silence) who works as the main street-level agent for some big-time operator known only to him, and who has been steadily scaling back his dealing activities ever since he used some of his profits to open up a nightclub-restaurant in the neighborhood. As it happens, Scatter was also the man who gave Priest and Eddie their start in the drug trade, and Priest hopes to capitalize on those old ties by pouring the whole of his and Eddie’s nest-egg into a monumental 30-kilogram cocaine buy. Scatter’s mysterious supplier peddles only the best, and Priest believes that once the blow has been cut for distribution, he and Eddie will be able to pocket fully a million dollars. With 500 grand to play with, Priest should be able to set himself up for whatever he wanted to do.

Scatter proves difficult to persuade, but Priest eventually manages. Priest’s army of street-corner dealers, meanwhile, look to be well on the way to achieving his goal of selling off all 30 kilos in four months. Nevertheless, there are several major hurdles standing between Priest and a life of material comfort that doesn’t involve him risking arrest or worse every damn day. First of all, most of the people in his social circle really don’t want him to quit. Eddie has no illusions about his post-Priest future, and he’s cooperating solely out of personal loyalty. Cynthia (Polly Niles), Priest’s white girlfriend, is as addicted to Priest’s coke-fueled cash-flow as Priest is to the coke itself. And of course there are all those street pushers like Fat Freddie, who will be left in the lurch when their boss calls it a quits. In fact, it seems the only person who does support Priest’s aim of retiring is Georgia (The Hitter’s Sheila Frazier, another member of the Three the Hard Way cast), the black hooker with whom Priest is conducting an affair far more satisfying to him than his “official” relationship with Cynthia. Bigger trouble still surfaces when the police bust Fat Freddie for beating the shit out of some guy in an alley. It turns out that Scatter’s shadowy supplier is really the deputy commissioner of police (Mike Richards), and Freddie’s interrogation yields a torrent of data that brings Priest’s big scheme to Deputy Commissioner Riordan’s attention. This is bad news because Riordan needs an accomplished agent in the field to oversee the distribution of his wares, and if Scatter doesn’t want to do it anymore, then the crooked cop intends to see Priest doing the job instead. And since those 30 kilos of coke with which Priest was hoping to finance his escape came from Riordan, the latter crime boss figures he pretty much owns the former. Scatter has some materials which he and Priest could use to blackmail Riordan into leaving them alone, but people who know too much about Riordan’s below-board business ventures have a funny way of turning up dead.

Superfly’s most obvious asset is one which it shares with Shaft— both movies are uncommonly convincing in their portrayals of urban blight. Gordon Parks Jr. doesn’t do quite as good a job of it as his father did the year before, but he’s still lightyears ahead of just about everybody else on the blaxploitation scene except Larry Cohen. The unifying factor here, of course, is that all three directors came by their urban blight the old-fashioned way; wherever possible, they shot their movies in the midst of the real thing. Furthermore, Superfly is able to wallow deeper than its illustrious predecessor in the misery and decay of early-70’s Harlem for the simple reason that its central character is himself an agent of that misery and decay. This brings us to one of the most interesting points about Superfly in comparison with Shaft, the curious way in which the two movies’ protagonists seem to mirror each other from opposite sides of the law. John Shaft exhibits little in the way of moral awareness per se, but seems instinctively drawn to do the right thing— albeit strictly on his own terms and in exchange for an often considerable fee. Priest, on the other hand, as a high-volume coke-pusher, is a destroyer of lives and a poisoner of communities, yet he has a fairly developed sense of right and wrong that is eating him up inside; as he tells Eddie, “I need to get out of this game before I kill somebody.” Of course, the odds are a decent percentage of Priest’s customers have ODed on his merchandise over the years, so he’s arguably already killed plenty of people. Nevertheless, the point stands that Priest sees how his involvement in the drug trade is pushing him inexorably toward violating whatever principles he has left, and that he’s perceptive enough to notice the difference between the reality of the crime-boss lifestyle and the glitzy illusion that suckered him in when he was a boy— and which he himself scrupulously maintains despite recognizing its patent fraudulence. Superfly has taken a lot of flak over the years for glorifying the drug trade (no less an authority than Joe Bob Briggs once called it “the ultimate over-the-top pimp lifestyle movie”), but it seems to me that the main effect of the film is to draw attention to the emptiness of Priest’s life, and to the hopelessness that dogs him as an ambitious son of the ghetto. It is the story of Priest’s desperate, last-ditch bid to escape from his “over-the-top pimp lifestyle”— which he adopted in the first place in the hope of escaping from the cul-de-sac of urban poverty— and its overarching tragedy is that the only way Priest can see to get away from what he has come to regard as a hateful moral compromise is to compromise himself even further in what amounts to the pusher-man equivalent of a gala going-out-of-business sale. Beneath the flashy clothes and the absurdly tricked-out Cadillacs and the gargantuan piles of cash trading hands every five minutes, Superfly is a grim and often deeply depressing film, and even Priest’s eventual (and probably inevitable, commercially speaking) triumph is haunted by the un-remarked-upon but ever-present specter of his own drug addiction, which seems more than likely to drag him right back to where he started sooner or later.

There’s a lot here for the actors to work with, and most of them do very well. Ron O’Neal exhibits just the right mix of superficial glamour and profound malaise, managing to seem simultaneously bigger than life and stunted by the burden of unbearable suffering. Carl Lee as Eddie is equally effective at dramatizing the fate that Priest is working to avert. Though it is never stated explicitly, it’s obvious all the same that Priest sees his future in his partner’s wholesale abandonment of the very concept of hope, and in his cynical disgust with everything up to and including himself; we see it too, and Lee’s quietly masterful performance is a lot of the reason why. Sheila Frazier also makes a strong showing for herself, elevating what might have been merely another cliched iteration of the Redemptive Woman by playing up Georgia’s weariness. It must have taken considerable bravery for an actress as young and attractive as Frazier to put herself across as used up and prematurely aged in a moderately high-profile Hollywood movie.

Finally, I would be remiss in not giving a nod to Curtis Mayfield, who wrote and performed the soundtrack for Superfly. His music here isn’t as flashy as what Isaac Hayes wrote for Shaft or as confrontationally stark as what James Brown wrote for Black Caesar, but it is just as evocative as either of those celebrated scores. The combination of blatantly repetitive grooves and Mayfield’s fragile-sounding falsetto subtly underscores the sense of futility and precariousness that lies at the heart of Superfly’s story. Blaxploitation as a genre was always unusually dependant upon its musical accompaniment, and Mayfield offers up a grade-A score to compliment a grade-A movie.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact