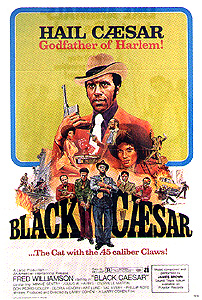

Black Caesar / The Godfather of Harlem (1973) ***Ĺ

Black Caesar / The Godfather of Harlem (1973) ***Ĺ

Itís probably only to be expected that the most ambitious of American Internationalís blaxploitation movies was directed by Larry Cohen. For one thing, the performance Cohen coaxed out of Yaphet Kotto in Bone, the directorís first feature film, gave him a reputation as someone who knew how to work with black actors. (Cohen himself is as mystified as anybody at the notion that directing blacks should require a different skill set than directing actors of any other race, but if it got him jobs, then he was perfectly happy to capitalize on other peopleís screwy ideas.) With that going for him, he was well placed to take advantage of the studioís celebrated willingness to let a filmmaker experiment provided that the finished product could still make a buck at the end of the day. But beyond that, Cohenís movies (even the lousy ones) have always reflected a desire to take on more than the conventional concerns of the typical exploitation picture. With Black Caesar, Cohen set out to make a blaxploitation movie that would deal seriously with issues that most of its ilk used as disposable plot devicesó racism, political corruption, the cancerous allure of the criminal lifestyleó while simultaneously paying conscious homage to the gangster films of the early 1930ís.

Fourteen-year-old Tommy Gibbs works as a shoeshine boy on the streets of Harlem. With no father in evidence and his mother (Come Back, Charleston Blueís Minnie Gentry) slaving away for minimum wage as a maid in an upscale apartment complex, we may imagine that Tommyís meager earnings are nevertheless a significant contribution to the household income, so it is readily understandable that the boy jumps at the chance when a man from the mafia offers him a relatively sizeable amount of money to do a little job for him. The mafioso is a hit man, and he wants Tommy to talk his target into having his shoes shined, and then seize the customerís leg so as to immobilize him long enough for the gangster to gun him down. So pleased is the hit man with Tommyís performance that he later hires him as a runner, carrying payoff money to a corrupt city cop named McKinley (Art Lund, from Bucktown and Itís Alive III: Island of the Alive). This second assignment for the mob doesnít go nearly as well. Itís never quite clear whether McKinley was shorted by his mafia clients, or whether Tommy sought to improve his position by taking a little something for himself out of the envelope he was sent to deliver, but the cop blames Tommy for the missing $50. McKinley beats the boy savagely with his nightstick, shattering his femur, and brings him up on some phony charge or other. We may assume that once Tommy gets out of the hospital, he spends the rest of 1953ó if not the entire time remaining until his eighteenth birthdayó in juvenile jail.

Skip ahead to October of 1965. Tommy (now played by Fred Williamson, of Hammer and 1990: The Bronx Warriors) is all grown up, and he has emerged from his latest stint in the lockup full of purpose and ambition. No more small-time scams for Tommy Gibbs; from this day on, heís going to make something of himself. Gibbs has heard through the grapevine that a mafia don named Cardoza (Val Avery, from The Legend of Hillbilly John and The Amityville Horror) has taken out a contract on a rival of his, and Tommy thinks it could be his ticket to the big leagues if he were to kill the marked man on spec, as it were. Tommy blows the mobster away while heís getting shaved at a Harlem barber shop, making sure everybody present has a chance to see that the man who pulled the trigger was black. As we see when Gibbs goes to meet Cardoza at the restaurant his organization owns, he had a very good reason for doing so. For one thing, everyone knows the mafia doesnít employ blacks, so Tommyís freelance hit leaves Cardoza safe from any reprisal. And of equal importance, Tommyís race simultaneously ensures that his own anonymity remains basically secureó it was a rare white guy who could tell one unknown Negro from another in the mid-1960ís. Theyíre both good points, and Cardoza can see that heís dealing with someone who knows his business, but what really breaks the ice with him is the way Gibbs places his order when the waiter comes over to see if he wants anything to eat. Tommy asks for a traditional southern Italian dish, and he does it in perfect, accent-less Sicilian; his cellmate during his last stay behind bars was an immigrant, and learning the language seemed like as good a way to pass the time as any. Gibbs isnít asking the don to give him a job and overturn the mobís longstanding ethnic policy (although he does expect the payment due him for shooting the other gangster). All he wants is for Cardoza to turn over to him a plot of territory in Harlem which the mafia has never been able to turn a profit on anyway. It sounds like a workable deal to Cardoza, and Gibbs is soon in business with his childhood friends, Joe Washington (Philip Roye) and the Reverend Rufus (DíUrville Martin, of Dolemite and The Legend of Nigger Charlie).

Over the next seven years, Gibbs turns his newly organized crime ring into one of the most vibrant and fastest-growing illegal concerns in New York, raising himself to a level at which even the haughtiest mafia dons are forced to deal with him as an equal. He even manages to set up franchise mobs in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit. Ironically, the key to Tommyís success is his old enemy, McKinley, who is now a captain of police and the front-runner to replace the retiring assistant commissioner of the NYPD. McKinley is just as corrupt as ever, and Gibbs has discovered that one of the mob bosses from whom the captain is on the take has been foolish enough to keep ledgers recording all his transactions with the various city authorities, all the way back to the late 1940ís. And as a further stroke of possibly deliberate luck, Gibbs happens to be dating a singer named Helen (Gloria Hendry, from Slaughterís Big Rip-Off and Black Belt Jones), who is a regular performer at the nightclub owned by the mobster in question. Gibbs raids the club after hours one night, kills the mafia accountant and his several guards while they go over the tallies for the day, and makes off with the incriminating ledgers. Then he gets in touch with lawyer Alfred Coleman (William Wellman Jr., of Itís Alive! and Macumba Love), who deals with just about every big-time criminal in New York City (and who, not insignificantly, also owns an apartment in the building which Tommyís mother cleans for a livingó if thereís one thing Gibbs loves, itís putting himself in power over those who once held power over him). Gibbs hires Coleman, and has him call in McKinley for a meeting. Joe, the practical brains of Tommyís operation, has put together an unusual bribe for McKinleyó a stock portfolio that should ultimately be worth more than he could reap from a lifetime of even the most burdensome cash kickbacks. This is a one-time deal; McKinley takes the stocks, and then stays out of Tommyís hair for good. And just to make sure the policeman understands what a generous offer that really is, Gibbs makes sure to have the mafia ledgers sitting conspicuously on Colemanís desk while he and McKinley negotiate.

Eventually, though, Gibbs gets too big for his britches and alienates too many people. He backstabs his old mafia benefactor and ruthlessly exterminates the mobs run by the rest of the Cardoza family out in California. His persistent putting off of his early promises to invest his ill-gotten riches in legitimate programs to improve Harlem leaves Joe disillusioned and resentful. He consistently mistreats Helen, until she finally starts up an affair with Joe after Tommy packs the two of them off to Beverly Hills to get them off the firing line of the brutal war he knows is coming between him and the mafia. He spurns his long-absent father (Julius Harris, from Superfly and Friday Foster) when he resurfaces in an effort to make amends. When Tommyís mother dies and Rufus finds religion for real, Gibbs finds himself with no allies left, and thatís when Coleman, McKinley, and the white organized crime establishment finally make their move. The victory will be a pyrrhic one for several of Tommyís enemies, but the Godfather of Harlem ends up falling nevertheless, his final defeat coming in the summer of 1972. Just how downbeat the ending is depends on which cut of the movie you see, however. In its first domestic theatrical run, Black Caesar concluded with Gibbs returning to the ruins of his childhood home to contemplate his similarly desolate future. The original ending, which played in European theaters and was restored for home video, is even bleaker, with Tommy being robbed and beatenó possibly to death, although the scene is somewhat ambiguousó by a gang of black street kids like he himself once was.

Believe it or not, Black Caesar was originally intended to be a Sammy Davis Junior vehicle. Davisís agent had offered $10,000 to Cohen to draft a screenplay, and it was the combination of the singerís diminutive size and fabled mob connections that gave Cohen the idea to rework Little Caesar, one of the first great gangster pictures, for a black cast and audience. The agent never came through with the money, though, so when Sam Arkoff called and asked Cohen to contribute to the A.I.P. blaxploitation onslaught, Cohen had no compunctions about using the script himself. It was all for the best, really, because Fred Williamson, Sammyís vastly cheaper replacement, has much to do with why Black Caesar works as well as it does. Tommy Gibbs is a character motivated almost completely by a desire to turn the tables on the whites who have oppressed, abused, and condescended to him all his life, and after seeing the fiery intensity that Williamson brings to the role, itís impossible to imagine anybody else (let alone Sammy Davis Jr.) matching up. His tigerish combination of size, poise, agility, and personal magnetism is also essential to the roleó he looks like a man who could never be outfought or out-charmed by anyone, and you can easily believe Williamsonís Gibbs seizing Harlem by the throat and making it his own.

Itís also worth pointing out that if Black Caesar had been fully developed as a Sammy Davis Jr. project, Cohen himself would almost certainly not have been hired to direct, and American International unquestionably would not have been the studio backing the production. Without Cohen and A.I.P., it seems unlikely at best that Black Caesar would have achieved the air of authenticity brought to it by its directorís guerilla filmmaking philosophy. Cohen claims that the officials from the various movie industry unions were afraid to follow him into the atrocious slums where most of the outdoor scenes were shot, and he tells a story about avoiding the necessity for kickbacks to the local black mobs (which had hamstrung a number of previous efforts to shoot movies in the neighborhoods where he was working) by hiring the mobsters themselves to play Tommyís gang. Nobody working for the majors would have had that kind of gall, and even if they did, they probably wouldnít have gotten away with itó Cohenís seven-man film crew obviously didnít have Hollywood-scale money on them, so the local thugs knew there was a finite amount that could be extorted from them in the first place. Beyond that, the limited resources available to Cohen and A.I.P. (Black Caesar was budgeted at about $450,000, and Cohen was hell-bent on bringing it in well below that figure) demanded an ingenuity that gives the movie a far more individual personality than it probably would have had with stronger backing. Astonishing as it seems, for instance, barely a scene in the film was shot on a soundstage; nearly every interior setting used was really one part or another of Cohenís own house, and the apartment which Gibbs buys from Albert Coleman actually belonged to Cohenís motheró as did the furs which Gibbs throws off the balcony one by one in a notably quirky scene. As a result, the indoor spaces we see have a natural lived-in look about them that would be difficult to duplicate in a studio.

In the final assessment, though, Black Caesarís greatest strength is Cohenís script, with its deliberate and systematic avoidance of formula commonplaces. Black Caesar is one of the few blaxploitation movies that never let you forget that their protagonists are criminals, and exceedingly ruthless ones at that. Tommy Gibbs pays an enormous price for his successes, and his failures are both manifold and painful. Even his revengeó whether symbolic or literaló against the figureheads of racism whom he hates so much proves hollow. While the stereotypical blaxploitation hero gets to go riding off into the closing credits in the back of a tricked-out limo, with a trunk full of cash and cocaine and a harem of white women taking turns sucking his dick all the way to the sequel, Gibbs is destroyed by his excesses, and even at the height of his temporary triumph, he remains a deeply unhappy man. Of all the films from the 1973 peak of the blaxploitation craze, Black Caesar is among the most honest, the least cynical. It pleases me to report that it was also among the highest-grossingó perhaps the public has some taste after all, eh?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact