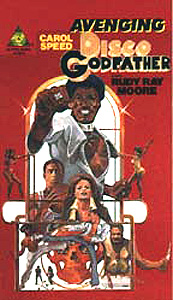

Avenging Disco Godfather/Disco Godfather (1979) -***½

Avenging Disco Godfather/Disco Godfather (1979) -***½

As many blaxploitation movies as there were in the 70’s, it’s difficult to believe that the craze for them petered out after just four years. There were a few tentative experiments at the very beginning of the decade, then Shaft opened the floodgates in 1971, and the vast majority of the 200-some films that can be plausibly classed as blaxploitation were released by the end of 1974. Even Italy’s short-lived peplum mania lasted longer than that! The 1974 cutoff date becomes even more surprising when you consider that one of the most significant players waited until that year to make his cinematic debut. Amazingly enough, Rudy Ray Moore’s big entrance came when the party was practically over— which I suppose makes his whole motion-picture career analogous to the one drunk jackass keeping the neighbors awake by hooting and hollering in the backyard until he passes out fifteen minutes before dawn, even though everybody else went home hours ago. Now that I think about it, that’s an extraordinarily apt comparison. It follows from his late arrival that Moore’s last blaxploitation movie of the 70’s may in fact be the last blaxploitation movie of the 70’s, although it’s hard to make such statements definitively about a genre that has attracted so little study. At the very least, Avenging Disco Godfather is the latest one that I know of, and we may glean some sense of how little market appeal blaxploitation retained five years after the boom times’ end from the desperation with which it plays the fad cash-in card as well.

It’s not unreasonable to ask at this point exactly what a “disco godfather” is supposed to be. I’m not sure myself, beyond that it apparently entails dressing like a bad Elvis impersonator and endlessly exhorting the crowd at your dance club to put their weight on it, whatever that means. In any case, that’s what Tucker Williams (Moore, whose previous screen appearances include The Monkey Hustle and Petey Wheatstraw, the Devil’s Son-in-Law) does at his disco dive, Blueberry Hill, and even the local paramedics call him “Godfather.” We know about the paramedics because Tucker’s introductory scene concludes with a truck full of them racing to Blueberry Hill to pick up his nephew, Bucky (Julius J. Carry III, from World Gone Wild and The Last Dragon), before he can injure himself or others in the throes of a PCP freak-out. Whatever town this is supposed to be has a real problem with angel dust lately, as Tucker discovers when he goes to see Bucky in the hospital, and Dr. Fred Mathis (Jerry Jones, who played alongside Moore previously in both Dolemite and The Human Tornado) shows him around the ward where he keeps all his drug casualties. Bucky is actually one of the fortunate ones in this company; he remains intermittently lucid, and there are worse things to hallucinate about than losing a basketball game to a team from Hell led by a sword-wielding devil-witch. For instance, Mathis’s star patient, so to speak, is a girl who served her honey-glazed baby as the main course at her family’s Easter dinner— she keeps going on about how the ham wouldn’t stop crying, and how she was afraid that was going to ruin the experience for everyone, but is otherwise uncommunicative and unresponsive to outside stimuli. The trouble Mathis faces is that PCP is relatively new as a street drug, and the physiological details of its effects on the human brain are poorly understood. (That was actually true in 1979, by the way. The earliest documented appearance of phencyclidine on the recreational pharmaceuticals market dates from 1967, and even today, some aspects of PCP psychochemistry remain to be sorted out.) Patients like Bucky, who experience breakdown early in the course of their addiction, often recover on their own with a bit of enforced bed-rest and the occasional mild sedative, but longtime users like the baby-baking girl are beyond the current reach of psychiatric medicine. Mathis is so totally at a loss for credible treatment options in severe cases that he’s even agreed to let that girl’s mother (Lady Reed, another Dolemite-Human Tornado alumna) bring in her bishop (Pat Patterson, who may in fact have been a bishop in real life) and church congregation to perform an exorcism! The tour of the angel dust ward steels Tucker’s resolve. He’s going to do something about this PCP shit!

Yes, I agree. Smashing the dust racket does seem just a tad outside the scope of a disco godfather’s normal responsibilities and qualifications. The nascent crusade begins to seem a trifle more reasonable, though, when it is revealed that disco godfathering is actually Tucker’s second career. Before he opened Blueberry Hill, Williams was a police detective, and he remains a reservist even in his highly idiosyncratic retirement. After leaving the hospital, Tucker pays a visit to the old precinct to compare notes with his former boss, Lieutenant Frank Hayes (Frank Finn). Hayes confirms the scale of the dust epidemic and welcomes Tucker’s assistance, but he also cautions Williams to stay within the limits of his powers and duties as a police reservist, and to go strictly by the book in whatever he does. Of course, we all know the chances of that happening in a 1970’s crime melodrama, right?

Tucker’s anti-drug activities follow two parallel tracks. As you’d expect of a B-movie ex-cop, he exploits the network of snitches and stooges that served his informational needs so well during his years on the force. He also leans on crime lords he knows who are not involved in the PCP trade— like Sweet Meat the pimp (Jimmy Lynch, from The Human Tornado and Petey Wheatstraw, the Devil’s Son-in-Law) and his mob— both to stay out of it and to refuse cooperation with any other criminal organizers who are involved. But at the same time, Williams pursues a second strategy that casts him more as a politician than an officially sanctioned vigilante. Joining forces with Dr. Mathis and a semi-retired veteran of the civil rights movement known as Old Bob (I think this might be West Gale, of Death Cruise and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, hiding behind a really shitty dye job), and using his personal assistant, Noel (Carol Speed, from Dynamite Brothers and Bummer!), as a liaison to the local church-based women’s groups, Tucker orchestrates a community activist alliance that he calls “Attack the Wack.” (I’m assuming that “wack” was a slang term for PCP that did not survive the 1970’s. I’ve never heard it anywhere outside this movie, but then I doubt that anybody in my lifetime ever called a marijuana cigarette a reefer, either.)

The identity of Tucker’s nemesis is also a bit outside the norm for this sort of film, and might have come as a surprise were he not so obviously sleazy from the moment we lay eyes on him. Stinger Ray (Hawthorne James, of Campfire Tales and Seven) is no Gator, Priest, or Tommy Gibbs— hell, he isn’t even a Goldie or a Willie Green— but rather an outwardly legitimate businessman. Just lately, his name has been in the press a lot in conjunction with plans to establish a minor-league basketball team— the very team for which Bucky and some of his dust-smoking friends were angling to play. I think we’re meant to deduce a connection between the two enterprises, like Stinger deliberately hooks his players on PCP to keep them tractable or something, but I can find no way to force that to make any sense. Regardless, Stinger doesn’t initially take Tucker seriously as a threat to him or his below-board business. I mean, would you? However, one of his accomplices is a crooked cop on Hayes’s staff, and Detective Kilroy (Sorority House Massacre’s Fitz Houston) knows Williams well enough from their time as coworkers to recognize that the disco godfather is much more than a clown in a sequined jumpsuit. Kilroy immediately advises his partner to eliminate Tucker, leading to a chain of events that I also can’t force to make sense. Having commissioned a hit on the disco godfather at Blueberry Hill as per Kilroy’s advice, Stinger changes his mind for no visible reason, and puts out a hit on the hit. The assassin assassins disguise themselves as beat cops, and arrive at the club just in time to gun down the original hitmen before they can open fire on the DJ booth where Tucker is spinning records and chanting, “Putcha weight on it! Putcha weight on it! Putcha weight on it!” Obscure though the motive for the attack may be, that bit with the uniforms might be a pretty good blind were it not for one thing: both of the disguised assassins are wearing badges bearing Kilroy’s number! Tucker doesn’t immediately know why he remembers badge 143 (neither does Lieutenant Hayes, bewilderingly enough), but it’ll click sooner or later. And when it does, the disco godfather will be just one step removed from being able to Attack the Wack at its source.

All of Rudy Ray Moore’s movies from the 70’s are bizarre, but Avenging Disco Godfather exceeds all of them in that department except maybe Petey Wheatstraw, the Devil’s Son-in-Law. It’s a film with a pronounced case of dissociative identity disorder, and its three alternate personalities are sharply in conflict at nearly all times. The title cues us to expect a ludicrous blaxploitation take on the disco craze, and the attached film dutifully gives us just that. Roller skating floor shows, deeply dubious fashions, fifth-rate Travolting— it’s all here, together with more “Putcha weight on it!” than anyone could possibly stand. However, this movie also gives us a barking-mad update of the old 1930’s drug scare routine, a veritable Phencyclidine: The Horse Tranquilizer with Test Tubes in Hell. Avenging Disco Godfather is at least on firmer pharmacological ground than most of those films, since PCP (unlike pot) actually can induce the kinds of psychotic episodes beloved by dope-panic movies of all eras. Even so, there’s a big difference between a psychotic episode and the kind of craziness that goes on in Dr. Mathis’s dust ward. This movie takes a really strange approach to the subjective hallucination scenes, too, almost like something Mystics in Bali director Tjut Djalil might devise under the inspiration of a David Lynch nightmare sequence. Then there’s the exorcism at the hospital, which goes on in fits and starts throughout the film, seemingly whenever director and co-writer J. Robert Wagoner is at a loss for a scene transition. It serves to inject the redemptive power of faith into the proceedings in a way that Dwain Esper or Willis Kent would have recognized at once, even though there was no longer any formal need for such moral fig-leafery in 1979. But at the same time, it was also plainly patterned after the exorcisms that were so prevalent in horror films over the preceding five years, which makes for a really jarring juxtaposition of form and purpose. And finally, there is yet another level at which Avenging Disco Godfather is a dark and gritty vendetta film in the Death Wish tradition., a depressing tale of a community succumbing to urban blight, and of one man’s quixotic quest to arrest the corrosion. One major character commits a gruesome suicide, another is beaten to death in his bed after his dog is gutted, and the ending— which is the only moment when the three alters ever really put their heads together and agree on a course of action— is as miserable and downbeat as it is overblown and ridiculous.

The strangest thing about Avenging Disco Godfather, though, may simply be its casting of Moore as such a thoroughly upstanding character. In all his previous film appearances, Moore played men who lived outside both the law and conventional moral strictures, despite being (at least in theory) essentially good at heart. Tucker Williams, however, is no honorable pimp or whatever. He’s a frigging ex-detective turned community organizer. He’s the initiator of a city-wide anti-vice campaign, and he’s considerably less on the edge than it was fashionable for movie cops to be in his day. He’s married— to an average-looking black woman about his own age!— and the whole plot hinges upon the importance that Tucker places on his family. (Like Hayes says, “There’s only three things you can do to that man to really get him uptight, and one of them is to mess with his family.” And now that you mention it, no— neither he nor anybody else ever says what the other two things might be.) And Attack the Wack? That is some square-ass shit for a Rudy Ray Moore character to be doing, but Avenging Disco Godfather nevertheless treats it with the utmost seriousness, and depicts the group’s activities quite realistically. They put on rallies, testimonials, and consciousness-raisings, hand out leaflets and petitions, solicit donations and recruit volunteers. They’re earnest and dedicated, and totally without sophistication of any kind. To return to the old D.I.D. metaphor, they belong wholly to the Grim Urban Despair Movie personality, despite the prominent roles played by Noel (otherwise a fixture of the Campy Blaxpo Disco Flick) and Dr. Mathis (who mainly inhabits the Dope Panic Do-Over). In short, they’re as far removed from Dolemite’s army of karate-trained hookers as Tucker is from Dolemite himself, and their presence in a story about a disco DJ’s battle against a drug-dealing would-be basketball impresario is in some ways even more surreal than the tawdry Halloween-costume monsters in Bucky’s hallucinations.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact