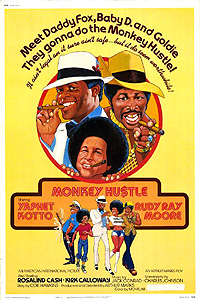

The Monkey Hustle (1976) *½

The Monkey Hustle (1976) *½

The first time I saw The Monkey Hustle, I was extremely disappointed. This is because it was promoted to me as a Rudy Ray Moore movie, when in fact Moore appears only briefly and infrequently, and although his character supposedly plays an important role in the story, he does so from behind the scenes, his involvement as invisible to the camera as it is to the other characters. But now, without those unwarranted expectations to cloud my judgement, I see that The Monkey Hustle is plenty sorry enough entirely on its own merits, redeemed only partially by a typically strong performance from Yaphet Kotto.

Kotto (also seen in Truck Turner and Friday Foster) plays Big Daddy Foxx, an “accomplished” petty crook who has learned to maintain quite a comfortable lifestyle in Chicago’s black ghetto without ever doing a day’s worth of honest work. And yes indeed, I put “accomplished” in quotes for a very good reason— any fool can see not only that Foxx’s scams are determinedly small-time, but that they invariably involve a ridiculous surplus of effort for the most paltry returns. Nevertheless, Foxx constantly has teenage boys pestering him to take them on as apprentices. Player (Thomas Carter), Tiny (Donn C. Harper, of Mimic 2), and Baby D (The Soul of Nigger Charley’s Kirk Calloway) are three such kids, and when they come to Foxx at the big warehouse full of dubiously acquired crap from which he operates, he agrees to employ them. This doesn’t go over well with Baby D’s big brother, Win (Randy Brooks), whose funk band has just come home from a string of disastrous out-of-town gigs, and who doesn’t want to see the younger boy getting himself mixed up in any criminal dealings. Even so, Win ends up a part of what Foxx calls “Monkey Hustle Inc.” himself— I mean, it’s not like he’s bringing in any money as a drummer, and he, his brother, and their unseen mom have to pay the bills somehow.

Truth be told, the troublesome ethics of Monkey Hustle Inc. are hardly Win’s biggest problem just now. That would probably be his girlfriend, Vi (Mandingo’s Debbi Morgan), who has taken up with a well-heeled older man named Leon in Win’s absence, despite the fact that her mother (Rosalind Cash, from The Omega Man and Dr. Black and Mr. Hyde) clearly likes Win better, broke though he is. Indeed, it would seem that the perceived need to compete with the money Leon is able to throw around goes no little way toward explaining how Win manages to overcome his scruples and sign up with Daddy Foxx.

Leon, incidentally, comes by his relative wealth by even more unsavory means than those Win is now contemplating. He works running numbers for another neighborhood outlaw hero named Goldie (Rudy Ray Moore, from Dolemite and Avenging Disco Godfather), who deals in much more serious forms of criminality than the pedestrian scams of Monkey Hustle Inc.— this despite the fact that, as his high school’s valedictorian from a couple of years back, you might expect Leon to make a legitimate future for himself. With Leon moving in the circles he does, the rivalry developing between him and Win could turn actively dangerous for the latter boy and his friends in the event that it ever escalated beyond the level of posturing and shit-talking.

Meanwhile, the city government is moving ahead on plans to construct an expressway on land currently occupied by the homes of thousands of low-income blacks. The project is being opposed primarily by a young man named Joe (Carl W. Crudup, of J.D.’s Revenge). Joe is unusual in the neighborhood for being college-educated, and as befits a well-read black man in the 1970’s, he’s also a local political activist. The alderman for his district, though having originally come from the ghetto himself, seems to have little or no interest in the concerns of his poorer constituents, and has been doing nothing to stop the expressway from coming through; consequently, Joe has been making a pest of himself down at city hall in the hope that his elected representative will get the hint that the highway measure is something he ought to be fighting tooth and nail. That’s where Foxx and Goldie could come in handy. Both men, despite being lawless parasites whose activities contribute much to the sorry state of the hood, are much loved in the ghetto, and both would be powerful allies in Joe’s struggle to win the vocal support of the community. Beyond that, Goldie’s ties to the hardcore criminal underworld give him a lot of potential pull with the corrupt city government, and word is the alderman owes him some mighty big favors from back in the day.

There’s a definite plot framework taking shape here, and strictly speaking, I suppose that framework does end up performing its expected function. After all, The Monkey Hustle ends with a successful demonstration against the highway, with the alderman putting in an appearance to soak up as much credit as he can for a victory he never really wanted in the first place. The trouble is, the seemingly weighty anti-highway plot thread is pushed so far into the background that virtually everything that advances it happens off-camera. Instead, the bulk of the running time is given over to a series of essentially unconnected vignettes of ghetto life. These vignettes— most of which concern either Win’s romantic woes or the activities of Monkey Hustle Inc.— never add up to anything like a coherent story, nor do the characters involved in them seem to evolve or develop in any meaningful way. Big Daddy Foxx starts out as a crook, and he stays a crook. His apprentices are never shown to have picked up enough tricks of the trade to become master scam artists in their own right, nor do any of them decide that a life of crime isn’t for them after all and resolve to go straight. Win gets Vi back too early in the film for the romantic conflict to carry any weight, and his band is still being given shitty, nowhere bookings and getting ripped off by their manager (Steven Williams, from House and Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday) by the movie’s end. Add in dialogue so jive-heavy that I could understand scarcely a word of the screenplay (though to be fair, I’m hardly The Monkey Hustle’s target audience), and the overwhelming impression the movie leaves is one of, “could somebody remind me again why I’m watching this?”

The Monkey Hustle has what might be an even bigger problem, though. After all, this is, at some level, a Message Movie, but the message it sends would be most charitably described as “confused.” Just about the only male characters in the film who aren’t some form of human garbage are Win and Joe, and the former of them puts up very little fight against his creeping corruption while the latter spends most of the movie on the sidelines. True, The Monkey Hustle’s sympathies are with Win, and the audience is encouraged to identify with him too, but the audience is also encouraged to approve of his ever-growing involvement with Daddy Foxx and his underhanded operation. Joe, meanwhile, is ultimately the one who saves the ghetto from the bulldozers, but his role in doing so goes almost entirely unrecognized. Admittedly, he is unsuccessful until he enlists the aid of Goldie and Foxx (to whom the film implicitly gives the credit for stopping the expressway), but neither one of those men had any independent interest in the cause— or in anything else, for that matter, beyond figuring out ways to live large without contributing in the slightest to society. The Monkey Hustle is ostensibly about the disenfranchised fighting the power and winning, but take a closer look, and you’ll see that the people who really suffer are the disenfranchised themselves. Everyone Foxx and his proteges rip off is both black and a resident of their own neighborhood. The charismatic beat cop known only as the Black Knight (Frank Rice, from The Gore Gore Girls) is on the take from every form of illegality, from petty gambling through prostitution on up. And don’t even get me started on Goldie. These are the men who make their neighborhood the hellhole that it is, and their work to save it from physical destruction hardly begins to make up for their continued efforts on behalf of its moral destruction. And yet nobody involved in making The Monkey Hustle seems to have grasped the point in even the most rudimentary way.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact