Coffy (1973) ***½

Coffy (1973) ***½

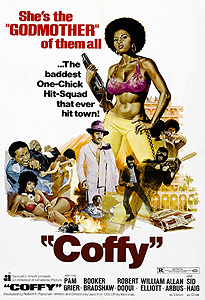

It wasn’t often that Samuel Z. Arkoff allowed himself to be outmaneuvered, but occasionally even his finely honed instincts led him astray. One such situation arose when American International was offered the screenplay for Cleopatra Jones. Incredibly, Arkoff didn’t think the script was worth the asking price, and so Warner Brothers ended up with the bragging rights for releasing the first high-profile blaxploitation movie with a woman in the central role. Arkoff and his studio came out swinging in the aftermath, however, releasing an eventual total of four films built around Pam Grier, the feisty young woman who had recently displayed such extraordinary sex-and-violence star power in a string of women’s prison movies from Roger Corman’s New World Pictures. Coffy was the first, and in most respects the best, of the cycle, a surprisingly hard-edged revenge melodrama written and directed by Jack Hill. Hill, like Grier, was a graduate of the New World women’s prison films, but what he serves up here is far more sober and aggressive than any of the light-hearted sleaze he created under Corman’s tutelage.

Somewhere in Los Angeles, a heroin dealer called Sugarman (Morris Buchanan, of Private Duty Nurses and Gas Pump Girls)— who, incidentally, sports a truly awe-inspiring bucket-shaped afro— is settling into a fun-filled night on the town when he is accosted by Grover (Mwako Cumbuka), one of his most dependable customers. Apparently in a generous mood, Grover has taken it upon himself to set his Dr. Feelgood up with a gorgeous junkie (Grier, from Black Mama, White Mama and The Arena) who says she’ll do absolutely anything for a fix. Sugarman initially resents the interruption, but then he gets a look at the girl and, well, I’m pretty sure the sight of her would be enough to make him forgive Grover for burning down his house, let alone barging in on his Friday night action. The threesome drive over to Sugarman’s place in the pusher’s beautiful royal blue Imperial (a car which will change owners almost as many times as the jeep in The Monster of Piedras Blancas), and Sugarman sets himself to romancing his date while Grover disappears into the bathroom to shoot up. That’s when things start to go haywire. Sugarman turns his back on the girl for a moment to see what’s taking Grover so long, and when he returns to her, she’s got a sawed-off shotgun pointed at his face. Turns out she’s not after heroin or sex, and a moment later, she blows Sugarman’s head right the fuck off of his shoulders before backing Grover into the bathtub and injecting him with something that sets off a lethal interaction with the heroin he’s already got in his veins.

It’s an incredibly ballsy way to begin a movie. We pretty much know going in that Grier’s character is going to be the heroine, and we think we have a fairly solid idea of how heroines— even action movie heroines— are supposed to behave. Consequently, it comes as an enormous shock when the very first scene culminates in her committing two cold-blooded murders. When Sugarman takes that shotgun blast to the face, we don’t even know the girl’s name! (As a matter of fact, we never will learn all of it. “Coffy,” the handle by which her friends know her, is merely a contraction of her blackly appropriate surname, Coffin.) Only gradually will we come to know the story of what led Coffy to take such drastic action, and by the time we have all the facts (Coffy, apparently an ex-junkie herself, has a younger sister whom Grover hooked on smack, and who is now little more than a human vegetable in a detox clinic outside of the city), there’s a chance that a good portion of the audience will already have written her off. Very few commercial filmmakers would be willing to take that big a risk.

Coffy turns out to be an emergency room nurse. She arrives at the hospital for her overnight shift visibly shaken up by what she has just done, and the doctor irritably sends her away when she proves unable to keep him steadily supplied with surgical instruments. (The fact that the patient on the operating table is an obvious gunshot victim probably doesn’t help Coffy’s composure any.) While she’s attempting to collect her wits, a pair of cops come in with word of the crime which she herself committed. One of the men is Sergeant McHenry (Barry Cahill); the other is his new partner, Carter Brown (William Elliot, from Night of the Lepus), an ex-boyfriend of Coffy’s with whom she has remained on friendly terms. Carter is frustrated by the corruption he sees on the police force and in the city government, and one gets the impression that his escalating distrust of politicians is at least as big a factor in his disapproval of Coffy’s current boyfriend as simple jealously; Coffy, you see, is dating City Councilman Howard Brunswick (Skullduggery’s Brooker Bradshaw).

Speaking of Brunswick, Coffy is supposed to go meet him after her shift at the hospital. It’s a big night for Howard, for not only has he just bought a controlling interest in a downtown nightclub with District Attorney Ruben Ramos (Ruben Moreno, from The Resurrection of Zachary Wheeler and Tarantulas: Deadly Cargo), but he’s also just accepted his party’s nomination for a seat in Congress. There’s something fishy going on here, though. While Howard, Coffy, and Ruben talk, they are observed by a one-eyed man (John Perak) who follows one of the cocktail waitresses to the bathroom and relieves her of her camera at knife-point when she happens to catch him in the frame of one of the snapshots she sells to the diners. This guy is obviously trouble, and either Brunswick or Ramos (or both) is obviously caught up with him somehow.

A few days later, Coffy takes Carter with her to see LuBelle (Karen Williams), her ailing sister. Afterwards, the two of them have a long, in-depth talk about political and police corruption, in which it comes out that the indigenous black crime syndicates of L.A. are being taken over by a mobster from out of town named Arturo Vitroni (Allan Arbus, of The Young Nurses and Damien: The Omen II), and that Vitroni has quite a few governmental and police officers in his pocket, too. Their conversation is interrupted by a phone call from McHenry, who is now revealed to be on the take from both Vitroni and one of his local minions, a pimp and pusher known as King George (RoboCop’s Robert DoQui). In fact, McHenry hopes to enlist Brown in his racket, but Carter isn’t having it. Unfortunately for Carter, the invitation is of the sort known in the business as an offer you can’t refuse, and within the hour, his apartment is broken into by a pair of ski-masked policemen who work Brown and Coffy over with baseball bats. The men flee before they’ve done much damage to Coffy, but Carter comes out of it with three ruined limbs, a shattered jaw, and severe brain damage. The doctor who treats him offers the prognosis that he might be able to go to the bathroom by himself one of these days.

Coffy might have thought her revenge against Grover and Sugarman was a one-time thing, but the attack on Carter changes the situation radically. From now on, she’s gunning for everybody who has anything to do with the crime empire that has destroyed both her sister and her best friend. Using a contact she made on the job— a call-girl named Priscilla (Carol Locatell, from Thunder County and Friday the 13th, Part V: A New Beginning) who once showed up at the hospital to have her slashed face put back together— Coffy tracks down King George and takes a position in his stable, posing as a Jamaican hooker named Mystique. What she really wants is a shot at Vitroni, but she manages to engineer King George’s downfall, too, while she’s at it. Her assassination attempt on Vitroni goes badly, however. The one-eyed man we saw at Howard’s nightclub was one of the don’s agents, and Coffy is recognized by both him and one of McHenry’s crooked cops; they and Omar (Sig Haig, of The Big Bird Cage and Spider Baby, or The Maddest Story Ever Told), Vitroni’s top lieutenant, set an ambush for her in Vitroni’s apartment. Naturally, it never occurs to the gangsters that Coffy could be acting of her own accord, and their efforts to figure out who is pulling her non-existent strings bring to light the cruelest betrayal of all— Howard Brunswick is a mafia lapdog, too! Brunswick will soon learn, however, that selling Coffy out to save his own skin is the single stupidest thing he could possibly have done.

That split-second shot of Sugarman’s head exploding into a zillion pieces may be the first time Coffy turns around and bites its audience, but it certainly isn’t the last. Though it looks like campy fun from a distance, this is a bracingly harsh movie that becomes bleaker and bleaker with every minute you spend thinking about it. There’s a scene about halfway in that sums things up perfectly. While Coffy is posing as one of King George’s whores, she earns the enmity of Meg (Linda Haynes, from Latitude Zero and Human Experiments), the pimp’s special favorite. This leads, inevitably, to a catfight in which Coffy takes on not just Meg, but every other girl in King George’s stable, and comes out on top. The fight scene does indeed contain the expected infusion of slapstick and titillation, but it rapidly progresses well beyond the traditional sexploitation slap-and-strip, with Coffy handing out judo throws and savage street-fighting moves. The climax of the sequence, which hinges upon Coffy having booby-trapped her afro with a set of razorblades, would sound like dark comedy if I described it, but Jack Hill plays it totally straight, and the next time we see Meg, she’s out of commission as a hooker with her hands swaddled almost completely in bandages. King George’s eventual execution at the hands of Omar and his thugs is also a deadly serious affair despite a certain cartoonish overkill, capable of stunning even a B-Fest audience into uncomfortable silence.

The real key to Coffy’s unexpected seriousness is Coffy herself. With her colossal afro, flashy clothes, and inexhaustible arsenal of snappy retorts and scandalous come-ons, it’s tempting to see Coffy as being cut from the same cloth as earlier Pam Grier characters like The Big Bird Cage’s Blossom. But upon closer examination, she has more in common with the psychically devastated avenging angels of the later rape revenge movies. By the final third of the film, vengeance is quite literally the only thing she has left. Coffy enters the story already driven to desperation by the fate of her sister, and things get systematically worse for her from there. She spends the first act haunted by remorse for the two murders she commits at the film’s beginning, searching futilely for a justification that will lay that remorse to rest. Then, just when she seems to be ready to come clean about her vigilantism, to put it behind her by standing up and facing the consequences, she sees Carter beaten nearly to death in front of her by men working for his own partner, leading her to embrace shotgun justice more tightly than ever before. Her subsequent activities bring her unanswerable evidence that the corruption she fights is overwhelming and all-pervasive, and in the end even her lover betrays her— twice in rapid succession! Coffy may triumph at the last, but her victory leaves her with nothing but scorched earth where a reasonably rewarding life used to be. Looked at from that perspective, Coffy seems less like a bargain-bin Cleopatra Jones than a precocious soul-sister Mad Max. It’s ugly and bitter and hopeless and mean, and its creators put forth its nihilistic message with a conviction that’s almost frightening.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact