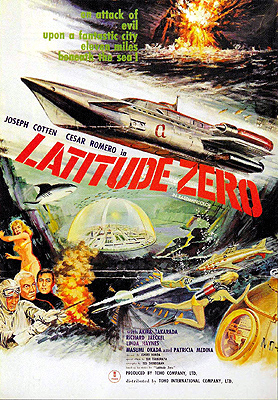

Latitude Zero / Ido Zero Daisakusen (1969) ***

Latitude Zero / Ido Zero Daisakusen (1969) ***

By 1969, Ishiro Honda, Eiji Tsuburaya, Shinichi Sekizawa, and Tomoyuki Tanaka had been the biggest behind-the-camera names in Japanese science fiction movies for fifteen years. Some combination of them had worked on every trendsetting sci-fi film released by the Toho studio since Godzilla: King of the Monsters, and on most of the trivial ones, too: Honda as director, Tsuburaya as special effects director, Sekizawa as writer, and Tanaka as producer. Latitude Zero was the last project that brought the whole gang together (Tsuburaya would die the very next year), and despite its obscurity in the West today, it’s a fitting capstone to the four men’s momentous collaboration. At a time when Japanese sci-fi was about to face impossible competition from well-funded American imports inspired by the success of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes; when it was moments away from a calamitous implosion in the scale of resources that domestic studios were willing to commit to it; when it was on the verge of transformation from an all-ages, general-audiences phenomenon into pure kids’ stuff, Latitude Zero was a microcosm of everything the genre had been since the mid-1950’s. It has super-submarines, a secret undersea utopia, monsters both giant and man-sized, scientific geniuses both malevolent and benign, sexy girls in skimpy outfits, and slumming Western B-listers for overseas marquee value, all squeezed together into a single, delirious film. And as a subtle bonus for the discerning Anglophone viewer, Latitude Zero is also the only movie in which kaiju eiga regulars Akira Takarada and Akihiko Hirata ever recorded their own dialogue for the English-language dub.

The Fuji, the world’s largest and most capable oceanographic research vessel, is on a mission to study the Cromwell Current, which runs at great depth through the equatorial Pacific. The plan is for two scientists, Dr. Ken Toshiro (Takarada, from The Last War and King Kong Escapes) and Dr. Jules Masson (Masumi Okada, of Sayonara Jupiter and The Living Skeleton), to descend to the current in a bathysphere packed with electronic instruments to take various readings on its physical properties and to record any unexpected phenomena they observe. Also aboard the Fuji is journalist Perry Lawton (Richard Jaeckel, from Day of the Animals and The Dark), who one gathers was never told exactly what he was being sent out to cover. He certainly seems dismayed enough when Toshiro explains the undertaking to him. Still, an assignment is an assignment, and Lawton is right there in the diving bell with the two whitecoats when an undersea volcano erupts directly below them, severing their link with the mothership, and tossing the bathysphere an ass-saving ten miles across the ocean floor.

Toshiro, Masson, and Lawton are rescued from the crippled bathysphere soon enough, but not by divers from the Fuji. Instead, their saviors come from the submarine Alpha, under the command of Captain Craig McKenzie (Joseph Cotten, from Gaslight and The Screaming Woman). It’s a very peculiar ship. Affiliated with none of the world’s governments, militaries, or private commercial fleets, the Alpha is nevertheless a great deal more sophisticated than even the most advanced submarines that are thus affiliated. Its pumpjet propulsion system can drive it at over three times the best speed of the US Navy’s latest Sturgeon-class nuclear-powered attack subs, and although the Alpha carries no significant armament, its defensive countermeasures are capable of projecting a completely convincing decoy of the ship to confuse not merely an enemy’s fire-control electronics, but their human operators as well. And incredibly enough, if the plaque on the Alpha’s bridge is to be believed, this wonder-sub was commissioned in 1805! Obviously something funny is going on around here. The short version is that you can basically think of Craig McKenzie as a gentler and cuddlier Captain Nemo, with the Alpha as his similarly gentler and cuddlier Nautilus. McKenzie’s base of opertions is an underwater city called Latitude Zero, located at the intersection of the Equator and the International Date Line. It is, of course, a perfect society of scientists, inventors, and explorers, but McKenzie is unexpectedly not its leader except perhaps in some very informal capacity. Indeed, Latitude Zero has no political organization at all. The undersea commune’s technology has triumphed over scarcity; no scarcity means no material want, and without material want, there’s no incentive for rational folks like these to behave antisocially. The three men from upstairs will be seeing this marvel of social maturity for themselves very soon despite McKenzie’s intentions to study the volcanic eruption that caused them so much trouble, because Masson’s injuries are too serious for Dr. Anne Barton (Linda Haynes, of Coffy and Human Experiments) to treat in the Alpha’s sickbay. He’ll have to be taken to Latitude Zero, where Barton and her colleague, Dr. Sugata (Akihiko Hirata, from Atragon and King Kong vs. Godzilla), can apply the full force of their medical wizardry.

Now just because Latitude Zero is a perfect society, don’t you go thinking they don’t have problems. Even Solla Sollew had its Key-Slapping Slippard, after all. Lattitude Zero’s biggest trouble dwells on an inhospitable island known as Blood Rock, and calls himself Dr. Malic (Caesar Romero, of Two on a Guillotine and Lost Continent). Malic is an outcast from Latitude Zero, a man for whom having every opportunity a person could ever desire somehow still isn’t enough. In his island stronghold, he conducts hideous Moreauvian experiments, creating giant rats, bat people, gryphons, and who knows what else. He lives in an astoundingly tacky late-60’s version of splendor with his evil consort, Lucretia (Patricia Medina, from Siren of Bagdad and The Beast of Hollow Mountain). And it’s only to be expected that Malic has a submarine, too. That would be the Black Shark, generally commanded by his other evil consort, Kuroiga (every source I’ve consulted identifies Kuroiga as Hikaru Kuroki, but I’m a little skeptical of that; “Hikaru” is usually a man’s name). As befits the creation of a diabolical genius, the Black Shark may lack the technical sophistication of the Alpha, but it more than makes up for that in speed and firepower. In any contest between the two vessels, the only hope for the Alpha is to sneak away under the cover of its sensory countermeasures and return to the safety of Latitude Zero’s impenetrable forcefield.

Inevitably, Toshiro, Masson, and Lawton are destined to find themselves in the middle of a clash between their hosts and Malic. The point of contention is one Dr. Okada (Tetsu Nakamura, from The H-Man and The Last Dinosaur), together with his daughter, Tsuruko (Mari Nakayama). Every so often, one of Latitude Zero’s scientists will go to the surface incognito to bestow upon the world at large some technological boon which the utopians deem us ready to handle, or to gather data for their own studies which cannot easily be accessed from the bottom of the Pacific. Okada has been on one such mission, but is now ready to return. Unfortunately, Malic wants whatever secrets Okada’s investigations have uncovered, and to that end, he sends Kuroiga and the Black Shark up to get him first. McKenzie figured Malic would try something like that, but he isn’t quite fast enough on the draw to thwart the abduction. So now instead, he’ll have to lead a rescue raid against Blood Rock. Toshiro and Masson volunteer for the mission out of solidarity with McKenzie and his people, whom they’ve both decided to join. Lawton, meanwhile, volunteers because he knows the scoop of a lifetime when he sees it.

Latitude Zero has possibly the most unlikely origin of any Japanese sci-fi movie. Shinichi Sekizawa and American co-writer Ted Sherdeman based the screenplay on a series of radio scripts that Sherdeman had written back in 1941. I have no idea whether the old “Latitude Zero” radio show was a fondly remembered hit in Japan, or whether Toho (who obviously wanted this movie to play well overseas) turned to Sherdeman in the mistaken belief that it was a fondly remembered hit over here. Either way, the considerable age of the source material perhaps goes some way toward explaining why Latitude Zero feels so divorced from the usual concerns of its era’s science fiction movies. The Cold War is acknowledged only briefly, mentioned in passing as a rationale for keeping the results of Okada’s research secret from the surface-dwellers. There are no aliens, no space travel, no supertech-enhanced espionage. And certainly the uncritical acceptance of Latitude Zero as a genuinely perfect society is far out of step with the turn toward pessimism about progress that would redefine the genre in the decade to come, and which was already visible in movies like The Monitors and Planet of the Apes. Instead, Latitude Zero looks backward a hundred years to Jules Verne, although the whimsical use to which it puts its Vernesque themes is both significantly more modern and distinctively Japanese. Whimsy is something that science fiction movies have largely forgotten how to do, so it pleases me to see it in such full flower here.

For example, just have a look around Blood Rock. My God, the lamé! The chiffon! The leopard print! This is the lair of a diabolical genius, remember, not the dressing room of a gay Vegas lounge singer. Meanwhile, the Rat Pack decadence of Malic, Lucretia, and their living quarters is juxtaposed against the retro-fascist aesthetic favored by Kuroiga and her sailors, which manages at the same time to hint at the ancient Middle East as imagined by Italians during World War I, much as the futuristic fashions of the 60’s “Star Trek” so often hinted at Imperial Rome or the Abbasid Caliphate. And the activities at Blood Rock are just as loopy as the look of the place, too. Malic may in theory be a conquering supervillian, but to all outward appearances, all he really does with his time is to make abominations against nature— not to any concrete purpose, but just because who wouldn’t want his own personal watch-gryphon, or a bunch of bat-people on staff to handle the hard jobs? Latitude Zero is an equally screwy place. Underneath its protective dome, McKenzie’s utopia suggests equally a scale model for next year’s World’s Fair and an illustration of the post-Second Coming future from a late-50’s Jehovah’s Witness propaganda tract. The people inhabiting it, in contrast, are a crazed hodgepodge of conflicting styles, explained by McKenzie as a result of the residents mostly preferring to stick with the fashions that were current whenever they took their leave of the surface world. That can’t account for the captain himself, though, who looks like a precocious High Disco version of a New York railroad baron summering aboard his yacht in the Aegean Sea, or for Dr. Barton, whose skimpy gold-vinyl costumes could have been designed by “Star Trek” tease-meister William Theiss himself. It’s frankly astounding that either Joseph Cotten or Caesar Romero could keep a straight face long enough to complete a single take.

As for Latitude Zero’s distinctive Japaneseness, I refer you back to the litany of genre characteristics from the opening paragraph. That said, it also goes a little further than that, into an area that might not be readily apparent to viewers who aren’t longtime, committed fans of these movies. One thing I find increasingly fascinating about Japanese sci-fi during the 60’s is its complete faith in the ability of humans and their institutions to get it all really right one of these days. Think about how King Kong Escapes or the more futuristic Godzilla movies treat the United Nations, for example. Far from the theater for international grandstanding that it was in the real world (and equally far from the inherently dysfunctional institution that it has since become in American pop culture, fit only to be denigrated, flouted, and ignored), the UN as imagined by Toho’s writers in the studio’s glory days is the seed from which a unified, democratic Earth is destined to grow. Latitude Zero is even more radically optimistic, with its utopian anarchist commune dedicated to unraveling the mysteries of the universe and advancing the aggregate knowledge of mankind. These people have evolved beyond any need for formal law or leadership, for institutions to restrain them from fucking each other over; hell, they’ve evolved beyond even the concept of property and all that goes with it. That kind of hopeful humanism, too, has become vanishingly rare in today’s sci-fi— I mean, even fucking Star Trek has gone all dark and edgy on us! I’m all for dark and edgy, as anyone who’s been reading these reviews for a while will doubtless have recognized by now, but I also like the opposite from time to time, especially in science fiction. Watching Latitude Zero in 2013 is like taking a vacation from negativity and nihilism.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact