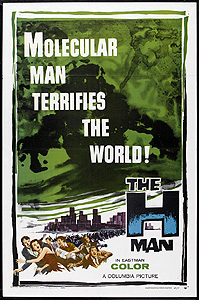

The H-Man/Bijo to Ekitainingen (1958/1959) **Ĺ

The H-Man/Bijo to Ekitainingen (1958/1959) **Ĺ

Itís easy to forget sometimes that not all Japanese movie monsters are 50 to 100 meters tall, even when H-bomb test-firings are explicitly responsible for their creation. The radioactive blob people of The H-Man, for example, are among the few atomic mutants in all of 50ís sci-fi to respect the law of conservation of mass. Radiation doesnít make them bigó it merely makes them very, very weird. In other words, it makes them a good fit for their own movie, because The H-Man is both a smallish film and a bit of mutant itself. Half uniquely unsettling sci-fi chiller and half deadly dull yakuza potboiler, it delivers something totally unlike what todayís audiences will instinctively expect from a movie of its genre and provenance.

Unfortunately, the deadly dull gangster flick is in the driverís seat at the outset. A drug dealer named Misaki (Hisaya Ito, from Ghidrah, the Three-Headed Monster and The Mysterians) has just finished stealing eight million yen worth of heroin from the post office locker of a fellow mobster when his getaway goes calamitously sour. Something grabs hold of his foot as he attempts to load the drugs into the trunk of his partnerís car, and Misakiís panicked shooting at whatever it is frightens the driver into speeding off without him. The gunshots naturally draw a crowd of gawkers, but all they see is the criminal lurching into the middle of the street to be flattened by an oncoming taxi. Misakiís body is in odd shape to say the least when the driver gets out to see how badly heís been hurt; in fact, itís essentially gone, the sole evidence that Misaki was ever there at all being his clothes, lying beneath the car just as if heíd melted out of them.

The briefcase full of dope didnít melt away, though, and it doesnít take the cops very long to find it when they come to investigate the strange incident. Next they find the forced-open locker in the post office adjacent to the scene of the action, which they trace to a known yakuza by the name of Chin (Tetsu Nakamura, of The Manster and Latitude Zero). Leaning on Chin nets the investigating detectives (about half a dozen of them, so poorly differentiated that I never did get a handle on which one was which) the information that Misaki was the only other person who should have known what was in that locker, and on that basis, the cops secure a warrant to search Misakiís apartment. All they find there is his girlfriend, a nightclub singer called Chikako (Yumi Shirakawa, from Rodan and The Secret of the Telegian), whom they promptly haul in for questioning. That proves to be less effective than the investigators would have liked. No one can find any illegalities to pin on Chikako, sharply limiting the detectivesí ability to coerce her cooperation, and besides, the bafflement she expresses at not having seen or heard from her boyfriend in days seems genuine enough. Itís even possible that sheís telling the truth when she says she never knew what Misaki did for a living.

One man who is not baffled by the criminalís vanishing act is Dr. Masada (Kenji Sahara, of Atragon and Godzilla vs. the Thing), assistant to Dr. Maki of the Tokyo Institute for Something or Other to Do with Radiation (Koreya Senda, from Battle in Outer Space and Varan the Unbelievable). Masada believes that the reason Misaki disappeared as if by melting out of his clothes is because he really did melt out of his clothes! The scientist arrives at this conclusion based on conversations heís had with a pair of fishermen he met when he was called in to the hospital to consult on their cases. The men had been hospitalized for radiation poisoning, you see, and their story explaining how they came down with it was a doozey. One night, their trawler came upon a seemingly deserted vessel not far (although they didnít know this part at the time) from the site of an American hydrogen bomb experiment. (Mary Celeste? Meet Fukuryu Maru. Fukuryu Maru? Meet Mary Celeste.) Their captain organized a boarding party to investigate, and the poisoned sailors were among those who were drafted for the mission. Once aboard the ghost ship, they could find no trace of the crew save their clothes, which lay all over the place in much the same state as witnesses to Misakiís disappearance would later report of hisó or at any rate, that was the only trace until the blobs appeared. Each consisting of about 60 kilograms of viscous, transparent, faintly luminescent liquid, there were about as many blobs as there should have been members of the ghost shipís crew, but no one in the boarding party caught the significance of that at first. They were too busy dealing with the fact that the blobs were not only alive and seemingly intelligent, but also deadly predators capable of reducing a man to a similar slick of glowing Jell-o with only a prolonged touch. (Incidentally, check out the second sailor to get melted by the blobs during the flashback that accompanies the survivorsí narrative; thatís Haruo Nakajima, Tohoís foremost monster-suit performer of the 50ís and 60ís.) The most frightening part of the boardersí ordeal came only after they escaped to the safety of their own ship, however. As their captain ordered a withdrawal from the vicinity of the monster-haunted vessel, several of the blobs could be seen slithering up above decks and reconstituting themselves into a vague approximation of the human form to watch the interlopers retreat, and that was when the sailors realized at last what the gelatinous horrors really were. Masada fears that Misaki was somehow exposed to the same form of radiation that liquefied the ghost shipís crew, and that heís sloshing around Tokyo even now, looking for people to melt into more creatures like him.

Now if I were trying to convince the authorities that the narcotics pusher they were hunting was so elusive because heíd been turned into a radioactive blob man, Iíd come prepared with every shred, scrap, and scintilla of evidence in my possession, and lay it all out for them step by step. Not Masada, though. In fact, the movie will be more than half-over before he so much as mentions those sailors in the hospital, let alone takes any of the detectives to hear their testimony. He just shows up at the nightclub where Chikako works after the cops have begun to stake it out in the hope of catching the singer in contact with either Misaki or one of his fellow gangsters (Did Masada read about Misaki in the newspaper? Itís the only thing I can think of that even begins to explain why the scientist would seek out Chikako.), and starts acting for all the world like somebody in urgent need of a good arresting. Then when Masada finds himself faced with exactly that, he goes out of his way to make the story behind his interest in Misaki sound even more preposterous than it did to begin with. Frankly, I wouldnít be surprised if the only reason why the detectives let him go is because they wrote him off as an annoying but harmless loony within the first two minutes of talking to him. Inevitably, though, Masada is absolutely right. The unseen thing that seized Misakiís ankle out in front of the post office that night was one of the sailorsí blob people; Misaki himself is now a blob person as a result of the attack; and when the pissed-off gangsters who soon show up trying to bully Chikako into revealing her boyfriendís whereabouts so that they can give him a piece of their minds start disappearing, too, itís because theyíre also being turned into blob people. So the questions become (1) how exactly does one cure, kill, or incapacitate a blob person, and (2) can Masada come up with anything slightly more persuasive than his personal say-so in support of his theory?

I expected to review The H-Man over eight years ago. It was scheduled to play at B-Fest 2004, but the film broke about fifteen minutes in, and no one in the projection booth could find a way to fix it. I saw just enough to make me think, ďDamn! Japanese showgirl costumes sure were skimpy in 1958!Ē I stand by that impression now, too, although obviously it wasnít the only one I came away with this time. My dominant reaction to The H-Man in its entirety is rather one of retroactive puzzlement over a pattern it emphasizes in Japanese sci-fi monster movies of the Showa era, the frequency with which these films use some manner of crime melodrama to kick-start the plot. Dagora the Space Monster, Gamera vs. Barugon, The Secret of the TelegianÖ Even Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster includes a bit of cops-and-robbers in its ridiculous five-car pileup of mismatched premises. The H-Man brings that realization to the fore because itís the first one Iíve personally seen in which the gangsters lack the good grace to go away once the monsters show up, or at least to fall into line with the main plot thereafter. The dumbass who tried to murder all his friends in order to monopolize the presumed market value of Barugonís opal-like egg was himself killed when the egg hatched on him, for instance, while the bank robber in Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster rightly decided that he had more pressing concerns than his stolen money once he found himself stranded on an uncharted tropical island amid four giant monsters and a nest of communist international bad guys. In The H-Man, by contrast, the boring yakuza business persists until practically the end of the film, constantly interfering with the nifty and disturbing story of Tokyo silently invaded by malevolent liquid mutants.

Thatís doubly frustrating because The H-Manís horror elements are so atypically effective. I canít think of any other movie that mashes up vampires with The Blob this way, and somehow the 1950ís commonplace of monsters taking away peopleís humanity and turning them into a singleminded Enemy Within gets an extra boost of skincrawl from the notion that they do it by melting their victims into puddles of glowing slime. Conversely, the Blob turns out to be scarier when itís not only intelligent but also formerly one of us. It was a wise decision to show the melting itself, too; the effect is cheap and primitive, obviously, but surprisingly convincing for all tható and all the more horrible for being a slow, messy, and yet eerily bloodless process. Honestly, the ghost ship flashback is worth the price of admission all by itself, especially the nightmarishly tranquil shot of the liquid mutants resuming a semblance of their erstwhile human forms all over their vesselís upper deck. Iíd long been curious about Ishiro Hondaís non-daikaiju monster movies, and thereís more than enough good in The H-Man to nudge Beast-Man of the Snow and Attack of the Mushroom People up a notch or two on my list of films to look out for.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact