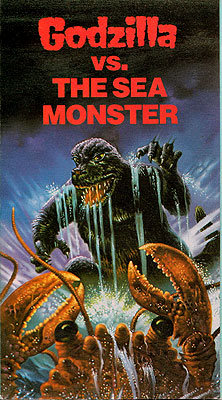

Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster/Ebirah, Horror of the Deep/Gojira, Ebira, Mosura: Nankai no Daiketto (1966/1968) *

Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster/Ebirah, Horror of the Deep/Gojira, Ebira, Mosura: Nankai no Daiketto (1966/1968) *

While it may not be the worst (hello, Godzilla’s Revenge...), Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster/Ebirah, Horror of the Deep/Gojira, Ebira, Mosura: Nankai no Daiketto is easily the most boring of the Godzilla movies. Beyond that, this movie has the dubious distinction of occupying a place in the history of the Godzilla franchise comparable to that of The Ghost of Frankenstein in the history of Universal’s Frankenstein series. Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster was the first of the cost-conscious Godzilla movies, the progenitor of a line that would culminate in the unbelievably shoddy Godzilla on Monster Island and Godzilla vs. Megalon.

It has frequently been observed that a monster appearing in a movie’s opening scene is a bad sign, and Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster falls right into line with that rule. It begins with a medium-sized boat being tossed about in a violent storm until it is finally destroyed by what appears to be a gigantic lobster. Then, “Two months later,” we see a woman consulting with a Shinto priestess about the fate of her son, Yata, who was on that unfortunate vessel. The priestess tells Yata’s mother that she has been unable to locate the boy’s soul in the land of the dead, and that Yata must therefore still be alive somewhere. Mom is overjoyed, and her other son, sixteen-or-so-year-old Ryota (Toru Watanabe), gets a major bug up his ass to go looking for him when he hears what the priestess had to say.

But before Ryota can go looking for anything out at sea, he’s going to need a boat, and that’s way out of the price range for a boy his age. His only chance is for his friends, Ichino (Chotaro Togin, from Yog: Monster from Space, who would return to the Godzilla series with 1967’s Son of Godzilla) and Nita (Hideo Sunazuka), to enter and win a dancing contest in which a small sailboat is the grand prize. (Note that this contest does not hinge on dancing skill, but rather on dancing endurance. The winner is the last dancer standing.) Ichino and Nita both drop out long before the contest is over, however, so they won’t be getting a boat that way. Ryota attempts to console himself by having Ichino, whose family apparently owns the local marina, drive him and Nita there to ogle other people’s yachts.

Before long, the three boys decide to take their ogling inside. They board a yacht called the Yahlen, and poke around for just long enough to discover that it is fully provisioned and ready to sail before the craft’s owner appears from inside one of the cabins, brandishing a rifle. The man’s name is Yoshimura (Akira Takarada, from Godzilla: King of the Monsters and King Kong Escapes), and he is not at all happy to see them. Why he lets the boys talk him into letting them spend the night onboard is anyone’s guess, but it was a singularly bad decision, because by the time Yoshimura awakens the next morning, Ryota has dismantled his gun and sailed the Yahlen far out into the Pacific. Yoshimura is less annoyed than he might otherwise have been for the sole reason that he had already been planning to take the boat out to sea the following afternoon. There are no police out at sea, after all, and when you’re a professional thief who has just heisted four million yen from the offices of some big corporation, anywhere with no cops sounds like a good place to be.

Or at any rate, it does so long as there are also no sea monsters there. Ryota’s instincts have been serving him well on the search for his brother, though, and after a few days, he ends up taking the Yahlen into the very same stretch of sea where Yata’s boat ran afoul of the giant lobster (which, by the way, is called Ebirah, though you’d never guess that on the basis of the American version). And just like Yata’s boat, the Yahlen soon finds itself storm-tossed, and headed straight toward a 35-meter lobster claw sticking up out of the water. The monster wrecks the yacht, and the four sailors are lucky to survive long enough to be washed ashore on a small mountainous island seemingly thousands of miles away from anything at all.

But as remote as the island is, it is far from deserted. Yoshimura, Ryota, Nita, and Ichino have managed to strand themselves on the secret headquarters of a cabal of high-tech international bad guys called Red Bamboo. Who are Red Bamboo? What is their agenda? Nobody knows, not even screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa, but it apparently has something to do with slave labor and heavy water, and the organization seems to have chosen this island in particular because here they have Ebirah to drive off any unwanted visitors; the monster is kept away from Red Bamboo’s transport ships with a repellant spray made from the pulp of some strange orange fruit that grows on the island. The castaways begin to discover all this when they witness a delivery of new slaves from the next island over, and accidentally attract the attention of some Red Bamboo soldiers. They narrowly escape by fleeing into the mountains, where they meet up with an escaped slave-girl named Daiyo (Kumi Mizuno, from Gorath and Frankenstein Conquers the World). Daiyo fills her new companions in on a bit more of the story, including the fact that Red Bamboo’s slaves come from nearby Infant Island (the home of Mothra), which, by a fortuitous coincidence, is also where Yata washed ashore two months ago.

This is where the rescue attempts begin. Daiyo naturally wants to free her people from Red Bamboo’s monster-repellant factory. Ryota, for his part, wants to go to Infant Island and bring back his brother. What everyone ultimately decides on is to begin by freeing the slaves, and then hijack a Red Bamboo ship to take back to Infant Island, whence Yoshimura, Ryota, Yata, Ichino, and Nita can make the voyage home to Japan. In actual practice, it doesn’t quite turn out like that. Yoshimura is able to break them into the Red Bamboo compound, but Nita is captured, Ryota is accidentally sent floating off to Infant Island on a reconnaissance balloon, and Yoshimura, Daiyo, and Ichino are forced to run back to the mountains for safety.

It is while they are hiding in a mountain cave from Red Bamboo’s forces that the three remaining protagonists make a surprising discovery. For no readily apparent reason, Godzilla is hibernating under their peak! Ichino then has the brilliant idea that if they could wake Godzilla up by directing into his body some of the lightning from the thunderstorms that frequently buffet the island, Red Bamboo would be too busy trying to deal with the monster to notice the three of them letting Daiyo’s people loose. All they’d need to pull it off is something to conduct the electricity, and Daiyo fortuitously stole a coil of copper wire from a Red Bamboo storage room when she was inside the compound. Meanwhile, back on Infant Island, the Twin Fairies (played, as usual, by Emi and Yumi Ito) are busily praying for the awakening of Mothra and overseeing the reunion of Yata with his newly arrived brother. And in Red Bamboo’s underground sweatshop, Nita is displaying the one flash of intelligence we’ll ever see from him, and instructing the slaves to make their next batch of Ebirah repellant without the active ingredient. Eventually, both Godzilla and Mothra awaken, and the real action begins at last. Mothra comes to its people’s rescue, while Godzilla beats up in rapid succession on Ebirah, Red Bamboo’s army and air force, and a big, stupid bird (apparently called Gai, though again you’d never figure that out from watching the US version) that just appears out of nowhere for no remotely defensible reason. Finally, Red Bamboo’s commanders, utterly defeated, set the self-destruct timer on the nuclear reactor that powers their base, and attempt to flee on one of their ships. Too bad for them Godzilla didn’t finish Ebirah off in their first encounter, because with Nita’s sabotaged monster repellant in their spray guns, the Red Bamboo bigshots have nothing to protect them from finding out how it feels to be on the other end of the chopsticks.

The first thing you’ll notice about Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster once the monsters finally appear is that, because the action is set on a remote tropical island, there are no cities around for them to smash. This is because city smashing costs money, and by 1966, Toho’s leadership were concerned enough about their profit margins that they wanted to spend as little of that as possible. Grosses had been declining steadily for the last three movies as more and more Japanese moviegoers decided to stay home and watch television instead, so another Ghidrah, the Three-Headed Monster was completely out of the question. This may have had something to do with the decision to put director Jun Fukuda in charge of the seventh Godzilla movie, instead of series founding father Ishiro Honda; Honda had directed nineteen sci-fi/monster movies by then, and only a couple of them could honestly be described as “cheap.” Fukuda, meanwhile, had directed only one such film— The Secret of the Telegian/Denso Ningen— and had done so on the same sort of budget he had used for the crime melodramas that were his primary stock-in-trade. That Fukuda was successful in controlling the cost of this movie is immediately obvious; unfortunately, that’s largely because there’s so little monster action involved.

What’s more, when that monster action does begin at last, it isn’t very good. Ebirah is an embarrassingly feeble opponent for Godzilla, particularly in comparison to King Ghidorah, his primary foe in the previous two movies. Indeed the new monster’s name pretty much says it all— “ebi” is Japanese for “prawn,” making “Ebirah” more or less equivalent to “Shrimpzilla.” Meanwhile, Mothra gives us yet another reason to ask, “explain to me again why this monster is so popular?” doing little but sleep throughout the film until the final ten minutes, when it swoops down to airlift the Infant Islanders to safety. And don’t even get me started about Gai. In fact, the one interesting thing in this movie related to the monsters is Godzilla’s reaction upon seeing Mothra: he attacks it, suggesting that even as late as 1966, when Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster was released, the folks in charge at Toho still weren’t quite comfortable with the idea of Godzilla as a full-on good guy.

The lack of kaiju action is not at all compensated for by the Bond-movie knock-off plot that occupies most of the film’s running time, either. Now, before I go on with this point, I think I should come clean regarding one of my personal biases. I hate the James Bond movies— every last fucking one of them. So it’s entirely possible that someone who enjoys those films— particularly the ones involving SPECTRE— will regard as a selling point what I think is the key to this movie’s downfall. To wit: Fukuda doesn’t really care about any of his four monsters; he only has eyes for Red Bamboo. So to my way of thinking, it is all the more serious a problem that nobody involved in making Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster seems to have bothered to figure this organization out. At least the Bond villains have agendas, even if they don’t make any sense (really, what would be the point of irradiating all the gold in Fort Knox?); Red Bamboo, on the other hand, are the bad guys basically because they look like SPECTRE, and somebody has to pick up the slack of villainy from the completely useless Ebirah. All we ever learn of the organization’s activities is that they somehow involve nuclear power or nuclear weaponry, and that Red Bamboo’s research and development department is going about it all wrong, at that.

Finally, there’s the music. Most of the time, I don’t really give a shit about background music in movies— hell, I usually don’t even notice it’s there. But the Godzilla series is different, because the Godzilla series has Akira Ifukube. Or at any rate, it did until Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster. Among the many ways in which Jun Fukuda decided to shake up the franchise was by replacing Ifukube with composer Masuro Sato. Sato’s score for this film is the final nail in its coffin. Its lightweight, painfully self-conscious hipness stands in embarrassing contrast to the effortless, unaffected majesty of even Ifukube’s weakest compositions. And the three-and-a-half decades that have passed since the movie’s release have left Sato’s score sounding hopelessly dated, further weakening what was already an inferior piece of work.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact