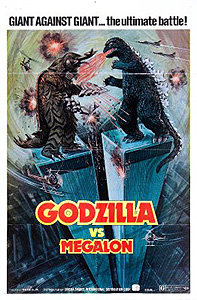

Godzilla vs. Megalon / Gojira tai Megaro (1973/1976) -***˝

Godzilla vs. Megalon / Gojira tai Megaro (1973/1976) -***˝

This may come as a surprise to some of you, but I like Godzilla vs. Megalon— and when it’s on the big screen, as opposed to the ass-crackulous pan-and-scan TV version I grew up with, then I frigging love it. I admit, it’s unlike me. I tend to like my Godzilla movies serious, or at least earnest, and in general, I have very few kind words to say for Jun Fukuda’s contributions to the franchise. Also, everything you’ve heard about this movie representing the absolute nadir of the series in virtually every conceivable respect is true and then some. It’s so cheap and shoddy that Godzilla on Monster Island looks positively epic in comparison, so silly and illogical that it makes one appreciate the insightful characterization and tight plotting of Frankenstein Conquers the World, so juvenile as to make Gamera vs. Guiron feel like a model of maturity. And to the best of my knowledge, Gamera, Super Monster is the only kaiju movie that comes by a larger percentage of its effects footage by raiding its studio’s film vaults. Yet despite all that, none of Fukuda’s Godzilla films save Godzilla vs. the Cosmic Monster even approach Godzilla vs. Megalon for sheer entertainment value.

This being a 1970’s Japanese monster movie, there has to be some not-quite-sane environmentalist message lurking behind the central conflict. Previous series entries had used the obvious “pollution-spawned monster” and “aliens from a pollution-wracked world try to take over ours” premises, so Godzilla vs. Megalon simply falls back on something even more obvious— that longtime kaiju eiga bugaboo, nuclear testing in the Pacific. It turns out that the Mu Empire wasn’t the only Atlantis-like sunken culture out in that vast ocean. The other is called “Seatopia,” and the continent supporting it sank beneath the waves some three million years ago, leaving only its highest peak above the surface. Possibly you’ve heard of said summit; most drylanders call it Easter Island these days. The Seatopians had been perfectly content to pursue a policy of strict isolationism ever since, but the A-bomb and H-bomb experiments that began in the 1940’s have rendered that way of life increasingly untenable. When a nuke of unprecedented power is set off in the North Pacific, triggering seismic disturbances all over the oceanic basin, the Emperor of Seatopia (Robert Dunham, from The Green Slime and Dagora the Space Monster, whose toga here unflatteringly reveals him to be one shaggy beast) decides that enough is enough. Surrounded by a ceremonial chorus line of cellophane-clad dancing girls, he declares war on the surface world, and awakens Seatopia’s monster mascot, Megalon. Megalon is basically a humanoid Hercules beetle 50 meters tall, whose forearms form a drill with which he burrows through the earth at tremendous speed. His horn shoots electrical discharges that look exactly like King Ghidorah’s breath weapon (for reasons that will become clear in the second act, when the stock footage from Ghidrah the Three-Headed Monster and Godzilla on Monster Island makes its inevitable appearance), and he can hock up explosive, incendiary loogies and spit them over distances of a thousand meters or more. He seems kind of impressive, so long as he isn’t being asked to fight anything tougher than a stock-footage army lifted from Godzilla vs. the Thing and War of the Gargantuas.

Meanwhile, some ordinary Japanese are finding themselves nearly as inconvenienced by the giant nuke as those weirdos beneath the sea. Well, okay— so maybe they aren’t exactly ordinary. One of them, Goro (Katsuhiko Sasaki, from Evil of Dracula and Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah), is an inventor. Another, Hiroshi (Yutaka Hayashi, of Assault!: Jack the Ripper and Wet Rope Confession), is a race-car driver. The third, Rokuro (Hiroyuke Kawase, from Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster and Time of the Apes), is an annoying little kid. It will take an attentive viewer indeed to catch the one time when the English-language dialogue identifies Rokruo as Goro’s little brother, and no unambiguous indication of the two adults’ relationship ever materializes. Most people will surely come away with the impression that Goro and Hiroshi are a couple of hip, swingin’ queers, and that Rokuro is the boy they abducted from the playground when he was about three years old. Anyway, the threesome are out for a lakeside picnic (Rokuro is riding some surreal aquatic conveyance built in the form of three fiberglass cartoon dolphins while the grownups watch him from the shore, swigging a rainbow-colored array of soda pop) when the bomb-induced earth-tremors hit, and Rokuro is nearly swallowed up when a crack opens in the lakebed, emptying it out like a bathtub with the plug pulled. The picnic well and truly ruined at this point, Goro, Hiroshi, and Rokuro return home, where they are immediately attacked from ambush by— Oscar Wilde?!?! Wilde (Kotaro Tomita, from Terror of Mechagodzilla and Ghidrah the Three-Headed Monster) on his own is about as tough as you’d expect an absinthe-raddled Victorian author to be, but his thuggish sidekick (Rika 2: Lonely Wanderer’s Wolf Otsuki) turns the tables on Goro and company long enough for the two intruders to make their getaway with a sufficient head-start that not even Hiroshi’s suped-up dune buggy (yep— it’s 1973, alright) can close the gap.

Obviously some sort of explanation is in order here. Remember how I said Goro was an inventor? Well, the latest thing he’s invented is a robot that Rokuro calls “Jet Jaguar.” Jet Jaguar looks just enough like a member of the Ultra Family to fall short of pissing off anyone at the Tsubaraya TV studio (who, as Toho’s frequent partners during this period, should not be needlessly antagonized), so he’ll probably be a pretty slick piece of hardware once Goro is finished building him. From the evident ransacking of the laboratory downstairs, Goro concludes that Oscar Wilde must have been after something related to Jet Jaguar, but there’s no indication that anything was actually stolen. The one real clue at the scene means nothing to anyone at the house, but I’m sure you’ll grasp the significance of the strange, reddish sand that Wilde and his accomplice tracked all over the place when a chemical analysis identifies it as a mineral sediment found only on Easter Island. That’s right— Wilde is a Seatopian agent, and his mission is to seize control of Jet Jaguar as soon as Goro has him up and running, so that the robot can guide Megalon to Tokyo for the big attack. Yes, I have to agree; that may indeed qualify as the worst world-domination scheme ever.

Goro forges ahead with the work on Jet Jaguar, and because he and his companions never do find the bugs Oscar Wilde planted all over their house, the Seatopians are able to keep abreast of his progress every step of the way. Once the robot is complete, the Seatopian agents kidnap Rokuro and use him to gain ingress to Goro’s home and lab. Then, with Jet Jaguar and his control console securely in their hands, they tie Goro and Rokuro up, conceal them in a steel shipping container, and hire a couple of unscrupulous truck drivers (Gentaro Nakajima and Sakyo Mikami) to dump it in a nearby river. (Those who have seen Godzilla vs. Megalon only on TV may be rather startled to discover that the nudie pictures festooning the cab of the truckers’ vehicle are clearly and unobstructedly visible in Cinema Shares’ US theatrical edit, which managed to get away with a G-rating anyway.) Luckily for the inventor and his brother, Megalon is on the rampage by then, and the truckers get scared off with the dumping unfinished. Hiroshi, meanwhile, comes home, beats some answers out of Oscar Wilde, and races off to the rescue. That entails the goofiest car chase since at least Women in Cell Block 7 and an egregious violation of physics (like, “Indiana Jones in a refrigerator” egregious), but Hiroshi gets the job done— which is more than we can say for a certain secret agent from the seafloor.

That rescue comes just in time, too, for Megalon has just about finished off the stock-footage military by now, and Goro knows of a way to interrupt the attack. Goro’s necklace doubles as a remote override control for Jet Jaguar, but it works only on a line-of-sight basis. Now that he’s free of that shipping container, Goro can talk the overmatched commander of the local JSDF garrison (Kanta Mori) into taking him up in a helicopter so as to regain control of the robot. Then, while the leaderless Megalon kills time knocking over whatever happens to be handy out there in the hinterland, Jet Jaguar can fly to Monster Island and summon Godzilla to deal with the Seatopians’ monster. In point of fact, Jet Jaguar goes that one better by returning to Japan after delivering the message, growing to titanic height (“He must have programmed himself to increase his size!” a rightly astonished Goro exclaims), and doing battle with Megalon himself. The Seatopian emperor, seeing how badly awry his invasion is going, calls in a favor from the Star Hunter M Universe, and has the inhabitants dispatch Gigan to Earth in support. Yeah, that’s a great idea. Gigan might have done okay against Godzilla the last time they tangled, but then he had King Ghidorah to back him up. This time, his intended tag-team partner is too clueless to find Tokyo on his own, and is in the process of getting his ass kicked by fucking Jet Jaguar when Gigan arrives.

Godzilla vs. Megalon was not originally supposed to be a Godzilla movie at all, but rather the launch vehicle for a brand new Jet Jaguar franchise. Jet Jaguar himself, meanwhile, was developed from the winning entry in a fan-feedback contest in which Toho invited kaiju kids across the land to devise new characters and submit them to the studio for consideration, and those two facts together explain a great deal about how the film turned out. Giant monsters were in decline on the big screen by the early 70’s, but tokusatsu and super-sentai shows were going strong on Japanese TV, to say nothing of the ascendant Go Nagai style of super-robot cartoons. Naturally, a character created via a nationwide fan-wank contest in that environment would come out looking like Ultra Kamen Fighter Z. And of course the ostensible lead kaiju would spend two thirds of the film doing nothing much beyond standing around on Monster Island looking like stock footage from four and six movies ago when the only reason he’s in here at all is that the producers got cold feet at the last minute, and started worriedly asking how many people were really going to buy tickets to see Jet Jaguar vs. Megalon. Since the answer to that question was plainly “fucking nobody,” it’s easy enough to see why Toho’s people did what they did, and with a glaring economy measure popping up in the completed movie about every five minutes at the outside (closer to every fifteen seconds once the action begins), it’s equally easy to see why they’d do it in the cheapest way open to them, retaining as much of the Jet Jaguar vs. Megalon script as possible.

It’s from that mostly recycled script that Godzilla vs. Megalon’s tremendous riches of glorious crap primarily derive. Simply put, there is not one damned thing in this movie that makes any sense whatsoever. To begin with, if the Seatopians are pissed off because of the damage caused to their kingdom by nuclear weapons experiments, then I think it’s safe to say that we can rule out Japan completely as the culprit. And yet where do the Seatopians send Megalon to register their discontentment? Straight to Japan. We’re told at one point that Seatopia has its own artificial sun, the product of literally millions of years of technological advancement, and yet we are also told scant seconds later that the underwater nation’s scientists and engineers have been unable to muster the resources necessary to create robots like Jet Jaguar— which a lone inventor among the “inferior” surface-dwellers was able to cobble together in his basement in his spare time. The Seatopians’ ultimate weapon is a monster too stupid to find its target unaided, and their plan for steering Megalon in the right direction depends upon the successful theft of a machine that hasn’t even been built yet. And while we’re talking about Jet Jaguar, let me return your attention for a moment to that “programmed himself to violate the law of conservation of mass” thing, and stress that only by the narrowest of margins does it manage to be the most ludicrous thing the robot does. Neither Goro nor Hiroshi appears to have anything resembling a paying job, and the house they share with Rokuro looks exactly like the “ideal homes” my friends and I used to draw sometimes instead of paying attention in Mrs. Walker’s fifth-grade history class. There’s a motor vehicle chase that involves all of the participants driving down a set of concrete stairs in a park. The movie concludes with Jet Jaguar striding off to embark on a career as an itinerant hero, while Goro and Hiroshi assure Rokuro that they’ll have a serious talk with “the scientists” so as to impress upon them the importance of letting the Seatopians be. And in an initially unobtrusive detail that becomes more glaring and more baffling with each passing moment after you notice it, this was the second consecutive Godzilla movie in which the Earth was besieged by a pair of monsters who didn’t have one prehensile appendage between them. Seriously, what’s not to love in all that?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact