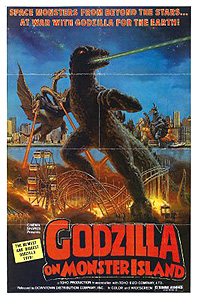

Godzilla on Monster Island / Godzilla vs. Gigan / Earth Destruction Directive: Godzilla vs. Gigan / Chikyu Kogeki Meirei: Gojira tai Gaigan (1972/1977) -**˝

Godzilla on Monster Island / Godzilla vs. Gigan / Earth Destruction Directive: Godzilla vs. Gigan / Chikyu Kogeki Meirei: Gojira tai Gaigan (1972/1977) -**˝

While it is neither as technically hopeless as the later Godzilla vs. Megalon, nor as brain-curdlingly bizarre as the previous Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, Godzilla on Monster Island is nevertheless one of the most misbegotten kaiju movies of the 1970’s. Its plot is essentially a daft reworking of Godzilla vs. Monster Zero, with aliens who aren’t what they seem using remote-control monsters in an effort to seize ownership of the Earth, but the familiar premise has been dressed up with Smog Monster’s bumbling hippies and alarmist environmentalism, and retargeted at the younger audience which had by then become the main market for sci-fi and fantasy films in Japan. What’s more, Godzilla on Monster Island was perhaps the chintziest Godzilla movie yet, with a substantial fraction of its action footage— and nearly all of its city-smashing— recycled from earlier films in the series. Keep your eyes open, and you’ll notice the main monsters’ appearances changing sharply from shot to shot, while kaiju who aren’t even supposed to be in the movie manage to sneak onstage for a few frames at a time in a couple of the secondhand scenes.

In the first obvious nod to the kids who were to be the film’s primary audience, we begin by meeting cartoonist Gengo Kotaka (Hiroshi Ishikawa) while he works on the monster-themed manga he hopes to sell to a children’s magazine. Kotaka did a bit of research before setting to work, interviewing his intended readership on the subject of what brings the highest levels of fear and anxiety to their lives, and as a consequence of his findings, he is building his latest comic strip not around some hideous creature from Japanese legend or some atom-powered enlargement of a familiar animal, but around the terrifying tag-team of Shukura (shuku is Japanese for “homework”) and Mamagon (“the monster of strict mothers,” in Kotaka’s memorable phrasing). The editor to whom he shows the new work is not impressed. Neither, for that matter, is Gengo’s domineering black-belt girlfriend, Tomoko Tomoe (Yuriko Hishimi, of “Ultra Seven”), who seems to be just a little bit annoyed that the pattern of scales on Mamagon’s belly bears a striking resemblance to that of her favorite dress (and who will indeed be using her karate skills to lay the smackdown on a few bad guys before all is said and done). Tomoko sends her good-for-nothing beau out to get a real job, and thus it is that Gengo ends up on the staff of a soon-to-open amusement park which goes by the imaginative name of “the Children’s Land.” (And don’t you go leaving off that “the”— everyone in the movie absolutely insists upon it.)

Now it might well be that the Children’s Land would make sense if you were Japanese; then again, since the people running it are really this movie’s alien conspirators, it’s also possible that we’re supposed to recognize the amusement park for the weird, weird place that it is. As Kotaka hears from Mr. Kubota (Toshiaki Nishizawa, from “Space Sheriff Gavan” and its apparent sequel series, “Space Sheriff Sharivan”), his new immediate boss, the Children’s Land is organized as a celebration of the two things which all children love: monsters and peace. Umm… okay. In addition to all the usual thrill rides and junk food and win-a-bunch-of-cheap-plastic-crap games, the Children’s Land features a huge tower at the opposite end of the park from the main entrance, built in the form of a life-sized replica of Godzilla. By the time the park is ready to open, the interior of this tower will house a museum dedicated to every sort of monster from all over the world. That, presumably, is where Gengo comes in; Kotaka even likes the idea of Shukura and Mamagon. And while it might seem at first as though the situation at Gengo’s place of employment couldn’t possibly get any more peculiar than that, that’s only because we have yet to meet the real master of the Children’s Land, seventeen-year-old mathematical genius Fumio Subo (Zan Fujita). How a teenager got to be the chairman of a multi-million-yen theme park is anybody’s guess.

Gengo gets his first clue to the mysteries surrounding the Children’s Land when he pays a visit to the corporate headquarters of its parent company the next day. On his way in, he bumps into a vaguely hippyish teenage girl (Tomoko Umeda) on her way out, leading her to drop the tape reel she was carrying. The girl runs off before Gengo has a chance to give it back to her, and something tells him to keep his mouth shut on the subject of tape reels when Kubota appears a moment later at the head of a gang of uniformed goons and asks his new subordinate which way the fleeing girl went. That evening, however, the girl from headquarters catches up to Gengo, and she isn’t alone— although, luckily for Kotaka, that cylindrical object her friend (Minoru Takashima) has pointed at his back isn’t really a pistol, but a foil-wrapped corncob. (It’s even weirder when you see it happening, believe me.) Turns out the girl’s name is Machiko Shima; the goateed guy with the corncob is Shosaku Takasugi. The reason they’re running around stealing tapes and threatening cartoonists with their lunches is that they’re trying to figure out what has become of Machiko’s brother, Takashi (Kunio Murai, from Godzilla 1985 and Ghost Story of the Snake Woman). Like Gengo, Takashi took a job at the Children’s Land, but he never came home from work one day, and nobody has seen hide nor hair of him since. It’ll be a while before our heroes figure this out for certain, but that’s because his employers have kidnapped him, ostensibly as part of a nefarious scheme to bring “peace” to Earth— by which they mean, naturally, to conquer it with giant monsters. The folks at the Children’s Land, you see, are in fact giant alien cockroaches who inherited a nearly dead world from the humanoid creatures which once dominated it, polluting their way to extinction and bidding fair to take every other species on the planet with them while they were at it. Only the roaches survived, and they’re now in the market for some slightly less fucked-up planetary real estate.

It is at this point that Godzilla on Monster Island stops making any kind of sense. I can tell you the following things: 1. The space bugs have commandeered the bodies of as many dead humans as they could get their tarsi on in order to pass unnoticed among us. 2. The Children’s Land is the base of operations from which they mean to orchestrate their conquest. 3. The instruments of this conquest are to be that perennial interplanetary troublemaker, King Ghidorah, and a hitherto-unseen cybernetic monstrosity called Gigan, whose appearance is so outlandish that the gigantic buzzsaw he has built into his chest is just about his sanest feature. 4. These monsters are to be controlled by means of the signals recorded on tapes like the one which Machiko Shima stole from Alien HQ, meaning that the space roaches are going to have to take on Gengo and his new friends if their plan is going to get anywhere. What I cannot tell you is: 1. why the aliens settled on a theme park as their cover story; 2. why playing the tapes to summon the space monsters initially has the effect of bringing Godzilla and Angiras rushing over to Japan from Monster Island instead; 3. why the aliens are so hell-bent on destroying the Earth-kaiju that they put their entire plan on hold in order to lead them into an ambush when to all appearances, the space roaches ought to be able to cue up another couple of tapes on their futuristic reel-to-reel and add Godzilla and Angiras to the invasion force; 4. why Godzilla and Angiras have suddenly acquired the ability to speak in electronically distorted voices; or 5. what in the hell the captive Takashi Shima really has to do with any of this.

Godzilla on Monster Island began life as an altogether more sensible script for a movie to be called King Ghidorah’s Great Counterattack, which would have had the three-headed space monster showing up with a few of his buddies (including Gigan and another monster which apparently never did make it into a movie) and crashing the World’s Fair, evidently drawn to it by the Japanese contribution— an enormous observation tower in the form of Godzilla. Over the course of the film’s development, supporting monsters were switched in and out, the motivation behind the attack from outer space became more and more complicated, and things became sillier and sillier overall. The one thing which never changed was the presence of King Ghidorah among the extraterrestrial invasion force, and I’m almost positive I know exactly the reason why. Simply put, Toho was planning on devoting very little money to the project, and the only way producer Tomoyuki Tanaka, director Jun Fukuda, and screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa were going to be able to present any really impressive action was to raid previous series installments for footage of clashing monsters and falling cities. Because no earlier Godzilla movie had featured grander action sequences than Ghidrah, the Three-Headed Monster, and because pillaging Destroy All Monsters could potentially have yielded footage of one-on-one combat between Ghidorah and virtually any other monster in the Toho stable, bringing the lightning-breathing space dragon back for one more round promised both spectacle and versatility at a bargain price.

The mere fact that “Which monster will buy us the most stock footage?” seems to have been the decisive factor in determining what form the 1972 Godzilla movie would take speaks volumes about the catastrophic state of decline in which the series found itself in the early 70’s. Even if we disregard the effects of the stock footage (and it isn’t easy to do that, let me tell you), this is an extraordinarily shoddy film, exemplifying an all-too-common approach to movies aimed mostly at a juvenile audience: “Hey, it’s for kids— who gives a shit if it’s any good?” But whereas the average movie made with that attitude is a trial at best and an ordeal at worst, Godzilla on Monster Island’s haplessness is such that it becomes consistently amusing and occasionally hilarious. The eagerness with which Sekizawa ditches unresolved plot threads as they lose their interest for him is little short of astounding, the much-anticipated reveal of the aliens’ true form is a minor triumph of making do on the cheap (Real cockroaches pinned beneath 1/24-scale debris! Brilliant!), and it’s a treat to see Godzilla fighting an opponent as screwy as Gigan— Toho’s kaiju had been getting steadily stranger for years, but Gigan looks more like an Ultraman villain than anything that had shown up in a Godzilla movie up to then. Godzilla on Monster Island is undeniably a mess, but unlike Jun Fukuda’s 60’s Godzilla movies, it’s at least a fun mess.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact