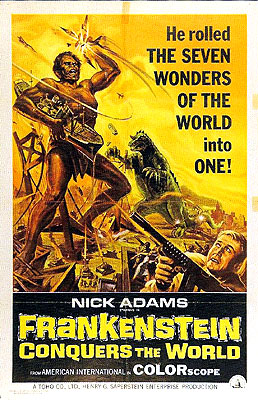

Frankenstein Conquers the World / Furankenshutain tai Chitei Kaiju Baragon (1965/1966) -***

Frankenstein Conquers the World / Furankenshutain tai Chitei Kaiju Baragon (1965/1966) -***

Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus has had a rough time of it from filmmakers over the last century. Sure, it’s probably inspired more movies than any other single novel ever written (though Dracula and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde certainly give it a run for its money), but for every Frankenstein or The Curse of Frankenstein, there’s been at least one Blackenstein or Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter. But of all the indignities heaped on Mary Shelley’s most famous work over the years by the movie industries of a dozen nations, it is difficult to find anything to equal the baffling defacement it received at the hands of Toho Studios in 1965.

The origin of Frankenstein Conquers the World/Furankenshutain tai Chitei Kaiju Baragon makes for a tale nearly as strange as the movie itself. It all began when King Kong special effects wizard Willis O’Brien got it into his head that the big ape had been ill-served by the shoddy sequel that was actually produced, and started kicking around ideas for a third Kong film at the turn of the 60’s. What O’Brien came up with was King Kong vs. Prometheus, in which the Prometheus monster was to have been a Frankensteinian creation made from mixed-and-matched outsized animal parts. He couldn’t get financial backing for the film, though, so he sold the idea to John Beck, a freelance producer formerly in the employ of Universal. Beck, in turn, sold it to Toho, in whose hands the project mutated into King Kong vs. Godzilla. But O’Brien’s screen treatment had made the rounds at the Japanese studio, and its giant patchwork monster inspired Toho producer Tomoyuki Tanaka and screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa to try their hands at a Frankenstein movie. Sekizawa initially tried to work the Frankenstein monster into a sequel to The Human Vapor, but nothing came of the plan. Nothing also came of later ideas by other writers to pit Frankenstein’s monster against Mothra and even Godzilla. Finally, in 1965, three different writers managed to come up with a Frankenstein script that satisfied the Toho execs, and work began, with the assistance of American producer Henry G. Saperstein, on Frankenstein vs. the Giant Devilfish. Now a “Giant Devilfish” and “The Subterranean Monster [Chitei Kaiju] Baragon” are rather different propositions, so clearly some explanation is in order. Baragon appears always to have been in the movie, but originally, the Frankenstein monster’s final battle was to have been against a giant octopus. Accounts vary as to whether the octopus ending-- which was indeed filmed-- was actually incorporated into the finished Japanese print of the movie; David H. Smith, in his essay on the film in Son of Guilty Pleasures of the Horror Film, says it was, while Stuart Galbraith IV, writing in Monsters Are Attacking Tokyo, suggests that it wasn’t. In any event, the octopus ending does not appear in American International Pictures’ U.S. version, which hit American theaters in 1966. Neither, for that matter, does anything which could remotely be construed as Frankenstein-- either the doctor or the monster-- conquering the world.

But we do get something every bit as daft as that. It is 1945 as the movie opens, and Hitler’s Third Reich is about to fall. Realizing the end is near, the Nazis send a U-boat to Japan, carrying a secret cargo of tremendous importance to the Japanese war effort. Is this precious cargo the secrets of the German atomic bomb program? No. Is it the Jumo 004B engine that powered the Me-262 jet fighter? No. Is it the blueprints for the Amerikabomber? For the Walther closed-cycle propulsion system for submarines? Of course not. This is something the emperor’s armies need far more than any of that: the immortal heart of Frankenstein’s monster! But the Japanese scientists never get a chance to do anything with the amazing organ (“this palpitating thing” in the memorable phrasing of one doctor), because the port to which it was sent happens to be Hiroshima, and the undying heart has been in the country only a couple of days when Little Boy levels the city.

Twenty years later, an American medical researcher named Dr. James Bowen (Nick Adams, from Godzilla vs. Monster Zero and Die, Monster, Die!) is at work in Hiroshima, studying the long-term effects of exposure to radiation, assisted by two Japanese colleagues, Sueko Togami (Kumi Mizuno, of Gorath and Attack of the Mushroom People) and Dr. Kawaji (Atragon’s Tadao Takashima). Bowen has become disillusioned with his work; at its current stage of advancement, it is of no practical value to the people he sees every day, dying slowly of radiation-induced cancer. Indeed, Bowen is seriously considering bagging the whole project and flying back to the States when something very strange catches his attention. It seems there’s a feral child loose in Hiroshima, supporting himself by killing and eating people’s pets. Bowen finds this so striking because it closely resembles reports he’d heard from the days of the Bomb’s immediate aftermath. Surely there couldn’t really be a connection?

Sure there could; this is a kaiju eiga, you know. When the townspeople corner the feral boy in a cave overlooking the sea, Bowen and Sueko take him into their custody at the hospital. There, they observe some mighty peculiar things about the kid. First of all, he has no apparent language skills-- he doesn’t even seem to grasp the concept of language. Secondly, he’s growing far faster than any normal child; within days, he’s as big as Sueko. But most importantly, he’s radioactive. In fact, his body seems to have absorbed at least twice the lethal dose of ionizing radiation, and yet he shows no signs of ill-health. Meanwhile, we in the audience are noticing something about the boy as well: his physical features strongly suggest Boris Karloff’s makeup in Universal’s 1931 Frankenstein. And considering that this movie is called Frankenstein Conquers the World, it seems likely that this particular peculiarity to the boy will wind up being the most important of all.

Meanwhile, at an oil-drilling station somewhere down the coast, evidence is coming to light that Japan may have something more dangerous on its hands. The drilling station is wracked by what appears at first to be an earthquake. But as the refinery buildings and drilling towers fall and the ground splits open to swallow them, the drilling foreman catches a glimpse of something moving beneath the surface. He doesn’t see it clearly or for very long, but it sure looks like a big rubber monster with a glowing horn on its nose. The foreman asks a coworker if he saw anything, but the other man says no. The second man then ribs his friend a bit about all the crazy things he’s always seeing: “In Hiroshima, back during the war, didn’t you see a heart that wouldn’t stop beating?”

The foreman, you see, had been in the Imperial Navy in 1945, deployed on the Japanese sub that met up with the U-boat carrying Frankenstein’s heart (and yeah, nobody in this movie seems capable of grasping the distinction between Frankenstein the renegade surgeon and the monster he built-- the characters uniformly say “Frankenstein” when they really mean his monster), and it was his submarine that actually brought the heart to Japan. For some reason, being reminded of the heart gets him thinking about the feral kid, and in a deductive leap that would stymie Sherlock Holmes, he concludes that the boy and the heart are somehow connected. He rushes off to see Bowen, and tells him what he knows. He then gives Bowen the address of the German scientist who last had custody of the heart, and suggests that the old man might be able to fill in some more of the blanks. Dr. Kawaji agrees to make the trip to Frankfurt to interview the doctor.

It is indeed the considered opinion of the German that Bowen’s boy is Frankenstein’s monster, his body grown anew from the heart as a result of exposure to the atom bomb. He even tells Kawaji how he can find out for certain. Frankenstein, you see, will regenerate any lost tissue if given enough time and nourishment, even something as complicated as an arm or a leg. The German scientist, in true Nazi war criminal fashion, suggests that Kawaji amputate the boy’s legs. If they grow back, and if the severed legs themselves remain alive after being cut off, then there’s no question but that the boy is the reborn Frankenstein; if not-- hey, he’s an untermensch anyway. The astounding thing is that Kawaji thinks this is a good idea! He can’t convince Bowen, though, and Sueko is even more adamantly opposed to the scheme. But Kawaji really wants to know the answer, so one night, after Bowen and Sueko have gone home, he heads downstairs to the cage where the boy has been living since he grew too big to let run loose in the hospital (he’s at least 18 feet tall by this point) with a cart full of surgical gear. He’s interrupted, though, before he can start cutting by a team of newsmen who have come to take pictures of the monster boy. The flashbulbs and klieg lights, combined with all the noise and unaccustomed activity, agitate the captive giant, however, and he breaks his chains, bursts out of the cage, kicks down the hospital’s wall, and flees into the night. But he’s left a souvenir behind: his still-living hand, torn from his wrist by the too-tight cuff of his manacle when he broke free! That settles it. The boy’s Frankenstein, alright.

Enter the Proper Authorities. The police and the J.S.D.F. chase Frankenstein around Hiroshima and the surrounding countryside, trying to catch him at first, but switching to a search-and-destroy approach after he starts causing damage in the hinterland. Frankenstein also ends up taking the rap for the activities of Baragon, the lizard/turtle/dog/armadillo monster that attacked the oil refinery earlier. But as it happens, the two monsters find each other before the army can find either of them. The ensuing clash consumes almost a quarter of the film’s running time before crashing abruptly into what is easily the most nonsensical denouement in the entire kaiju eiga canon. Frankenstein simply sinks into the earth after defeating Baragon, with nary a hint of excuse or explanation!

It’s a fitting end for a movie that spends its entire length beggaring reason. As the first full-fledged collaboration between the Japanese and American cinema industries (For once, a Western actor shows up in a kaiju eiga he was supposed to be in!), you might expect Frankenstein Conquers the World to show a bit more restraint in this department. After all, it was understood from the beginning that American audiences would be seeing this movie too. And yet, far from reigning in the legendary craziness of Japanese sci-fi/horror/monster movies, U.S. co-producer Saperstein allowed his Japanese colleagues to run absolutely wild with one of the best-recognized figures of modern Western mythology. Even 35 years later, Frankenstein Conquers the World is among the most demented movies Toho ever made, and it is frankly beyond my powers even to speculate how this happened with an American moneyman (who, let’s face it, could be expected to harbor certain pre-conceived notions of what a Frankenstein movie ought to look like) looking over the shoulders of the Japanese creative team. All I can say is, there was weirder still yet to come. In 1966, the same team would bring us a sequel so outlandish that Saperstein apparently thought it wiser to pretend it was an unrelated film when it reached American shores. I’m talking, of course, about War of the Gargantuas.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact