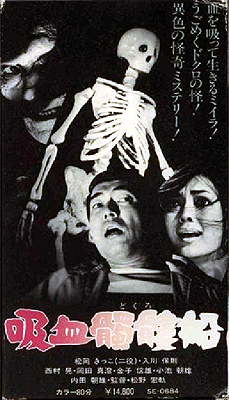

The Living Skeleton / Kyuketsu Dokorosen (1968/1969) ***

The Living Skeleton / Kyuketsu Dokorosen (1968/1969) ***

Happily, it turns out that there’s at least a little bit more where Goke: Body Snatcher from Hell came from. Shochiku, Japan’s most venerable continuously active film studio, didn’t make many horror or monster movies in the late 1960’s, but from what I’ve seen, those that do exist are all endearingly, compellingly weird. The Living Skeleton splits the difference between the sheer kookiness of The X from Outer Space and Goke’s unsettling bleakness and misanthropy. For the first hour, it looks like it’s shaping up to be the best Shochiku spookshow yet, but it stumbles in the home stretch with a third act that, although perfectly serviceable for what it is, rightly belongs to some other movie altogether.

Three years ago, a freighter called the Dragon King disappeared at sea with all hands. Her fate was never discovered by anyone not onboard at the time, but the natural assumption has been that the ship went down in a typhoon. The truth is grimmer even than that, however. The Dragon King was seized by mutineers who coveted her cargo of gold bullion, led by a man called Tanuma, whom we see only fleetingly, or in such tight closeup that he becomes merely a vague impression of opaque sunglasses and a horrendously scarred scalp. First among the casualties of the mutiny were ship’s physician Dr. Nishizato (Ko Nishimura, from Snake Woman’s Curse and The Ghost of the One-Eyed Man) and his wife, Yuriko (Kikko Matsuoka, of Black Lizard and The House of Sleeping Virgins), but the criminals were obviously intent on leaving no witnesses alive if they could help it. Once the deed was done, Tanuma and his men loaded the gold onto one of the Dragon King’s motor launches, and set off for Hong Kong to cash in the stolen cargo, leaving the ship herself adrift and unmanned in the Pacific Ocean.

Yuriko had an identical twin sister by the name of Saeko (also Kikko Matsuoka), and the former woman’s unexplained disappearance left the latter pretty messed up. Friendless and despairing in Tokyo, Saeko came under the influence of Roman Catholic priest Father Akashi (Masumi Okada, from Latitude Zero and Sayonara, Jupiter), who helped her straighten out her life, and brought her along as a sort of combined housekeeper and personal assistant when he took over a spooky little church in some out-of-the-way coastal village. Those who are well acquainted with Japanese genre cinema will realize at once that nothing good will come of Saeko’s association with Akashi, but kudos to anyone who can predict what specific ill his religious affiliations bode for her at this early stage of the game. For now, the only problem they’re causing her is the tangle of conflicting guilts that she feels over dating a local fisherman called Mochizuki (Yasunori Irikawa, of Trapped: The Crimson Bat). On the one hand, Akashi obviously wouldn’t approve of her having an affair unblessed by the sacrament of marriage. But on the other, Mochizuki does want to marry Saeko— it’s just that she feels so obligated to her priestly rescuer that she simply can’t see herself giving any other man the kind of claim over her that a husband would command. And naturally there can be no prospect of her ever wedding Akashi himself. Pity she couldn’t have fallen in with a Protestant missionary instead, huh?

Anyway, although Saeko has mostly gotten on with her life at last, there is one respect in which her sister’s disappearance continues to trouble her. She and Yuriko had a bond that went far deeper than what siblings— even twins— normally experience. For as long as Saeko can remember, they were so perfectly attuned that they seemed to experience each other’s emotions directly, even when they were physically far apart. Saeko knew, for instance, that something terrible had happened to Yuriko three years ago. And yet for that very reason, Saeko remains convinced that her sister is not dead, despite all the completely reasonable arguments that anyone might make to the contrary. In some way she could never possibly explain, she continues to feel that that channel to her sister’s heart remains open, even though no intelligible signal has come through it during the past three years.

While scuba diving together one afternoon, Saeko and Mochizuki have a weird and frightening experience. They see at least half a dozen human skeletons seem to materialize out of the inky water directly in front of them. Furthermore, we’re in a position to notice something about those skeletons which the divers themselves can’t fully appreciate: their ankles are all chained heavily together, in exactly the same way as the Dragon King mutineers had incapacitated the rest of the crew before turning their Tommy guns on them. Even without the aid of that clue, though, Saeko is certain the aquatic apparition has something to do with Yuriko, whether or not she understands how. She’s trying, without much success, to explain that to Mochizuki that evening when the two of them witness an altogether more obviously germane manifestation, the return of the Dragon King herself! The booming of a foghorn calls the pair to the window of Mochizuki’s house looking out across the sea, and although one rusty old freighter admittedly looks much the same as another, Saeko knows at once that she simply must go to the ship lying faintly silhouetted against the eastern horizon. She drops everything and rushes down to the pier below for a motorized dinghy, and it’s all Mochizuki can do to keep up with her. Evidently the secrets of the Dragon King are for Saeko’s eyes and ears alone, however, for no sooner does the little boat draw within swimming distance than a sudden wave washes both passengers overboard. The current carries Mochizuki and the overturned dinghy away from the ship, even as Saeko is pushed not merely toward her, but toward the chain ladder hanging as if in welcome over the port bow. Mochizuki evidently doesn’t see that, though. He returns to land as soon as he can get the dinghy righted, and alerts Father Akashi of the accident. Saeko, meanwhile, climbs aboard the Dragon King, where she finds first the ship’s log hinting at Tanuma’s brewing mutiny, and then Yuriko herself— or perhaps her ghost, or perhaps something else in between.

A similar puzzle confronts us when Akashi’s prayers for his protégé’s safe return are seemingly answered late that night. Is the bedraggled and strangely withdrawn woman who arrives on the front steps of the church Saeko or Yuriko— or again perhaps something in between? The mystery deepens in the morning, when she disappears again, and a dead girl washes up on the beach. Naturally Mochizuki fears at first that Saeko has committed suicide, but the corpse in the surf is no one he’s ever seen before. Her name was Rumi, and she was an employee and mistress of Suetsugu (Nobuo Kaneko, from Godzilla 1985 and Curse of the Blood), the proprietor of a cabaret in the nearest city. Suetsugu was also Tanuma’s right-hand man in the Dragon King mutiny, and the seed capital for his club came from his ill-gotten gains. Neither he nor his other mistress, Mayumi (Kaori Taniguchi, of G.I. Samurai and The Last Days of Planet Earth), thinks to connect Rumi’s death to that years-old crime, but it’s a different matter when Eijiri (Asao Uchida, from Spook Warfare and Return of Daimajin), another former mutineer, turns up at the cabaret, stinking drunk and blubbering about having seen Dr. Nishizato’s wife at the train station near the racetrack. At first, Suetsugu assumes that Eijiri, who gambled away his share of the loot almost as soon as he returned to Japan, is attempting to run some incoherent blackmail scam on him, but he sees for himself that something more sinister is afoot when somebody (her silhouette is a dead ringer for Saeko’s) opens all the gas taps in his house while he and his wife (Keiko Yanagawa) are sleeping.

Soon thereafter, in Chiba, another of Tanuma’s followers by the name of Tsuji (Asao Koike, from Orgies of Edo and Inferno of Torture), who sank his share of the mutiny’s proceeds into local real estate, also spots Saeko (or Yuriko, or whatever) hanging around his habitual haunts. Tsuji immediately contacts both Eijiri and Suetsugu (the latter of whom is but the first of three characters in this movie who will survive being plainly killed without a word of explanation or even acknowledgement), and invites them to his place to discuss strategy. Both men come at once, together with Mayumi (Mrs. Suetsugu will not be shrugging off her death by asphyxiation, despite identical circumstances to her husbands’), but there’s initially no consensus regarding what they’re really facing. Suetsugu, Tsuji, and Mayumi are all far more willing to entertain some supernatural hypothesis, though, once Eijiri dies gruesomely and inexplicably while showering after pillaging the lot of them at mahjong.

Meanwhile, Akashi gets an enigmatic letter in the mail from Saeko, begging his forgiveness, and exhorting him not to come looking for her, but assuring him that she’s safe and sound somewhere on the Chiba coast. Obviously Akashi and Mochizuki do come looking, though, catching up to Saeko at a fateful moment indeed. Ono (Toshihiko Yamamoto, of Goke: Body Snatcher from Hell and Hide and Go Kill 2), the last of the four men who followed Tanuma into mutiny, now works as a salvage diver. While attaching tow hooks to somebody’s submerged car beneath the end of a pier, he is set upon and drowned by a pack of skeletons identical to those whose appearance before Saeko and Mochizuki heralded the onset of all this deadly weirdness. Saeko, coincidentally or not, is on the beach nearby as Ono’s coworkers lift car, skeletons, and freshly killed diver alike out of the drink. That’s not only when Akashi and Mochizuki arrive looking for her, but also when Suetsugu, Tsuji, and Mayumi arrive looking for Ono.

Mochizuki is fool enough to believe that his reunion with Saeko means that everything will now go back to normal. The surviving criminals, on the other hand, have not been privy to that side of the drama, and therefore have no reason to delude themselves thusly. They may not realize that Mrs. Nishizato had a twin sister, but it’s obvious to all of them that they’ve been marked for death by somebody. Furthermore, they all realize by this point that that somebody is capable of doing things normally understood to be impossible. Suetsugu, still thinking small despite everything, is inclined to try splitting up and running away. Tsuji, however, contends that their only chance of survival is to stick it out together. And given that their persecutor (mortal or undead, as the case may be) appears to be seeking revenge for the victims of their mutiny, sticking it out together is going to mean doing something that none of them have hitherto had any desire to attempt. They’re going to have to find their old ringleader before the enemy does. Mind you, that won’t be easy, for exactly the same reason that the mutineers now see Tanuma as their best hope. Before he got into the commercial sailing business, Tanuma had been a secret agent— and despite The Living Skeleton’s late-60’s release date, we’re very much talking about the “killing people whose loyalties are inconvenient to the state, and organizing political violence in Third World countries” kind of secret agent here, rather than the “driving an armored Aston Martin, and banging Luciana Paluzzi” kind. When people with that skill set want to stay out of sight, there generally isn’t a lot that ordinary schmucks can do to flush them out.

Meanwhile, Saeko has a confession for Father Akashi. Although it’s a mystery even to her how she’s been doing most of it, she recognizes full well that she’s been transformed into an agent of her sister’s vengeance. Yuriko’s spirit took at least partial possession of her body when she went aboard the Dragon King that night, and it will not be satisfied until all of her killers are punished. Saeko thus has three more transdimensional assassinations to facilitate, and no real choice about whether or not to carry them out. What Saeko doesn’t realize as she spills her guts about all this to the priest is that she’s talking to her ultimate target. That’s right— Father Akashi is really Tanuma himself! However, Tanuma too is operating under a serious misapprehension, for he assumes that Saeko is talking crazy, and that she somehow or other eliminated two of his former followers by ordinary means. Maybe if he’d kept in touch with the other mutineers, he’d realize that even killing Saeko isn’t going to solve the problem now.

The Living Skeleton is an uneasy mix of two modes that I’d certainly like to see more of in the movies, albeit not necessarily together. On the one hand, it strongly evokes the sea-salt-flavored ghost stories of F. Marion Crawford, and on the other, it owes an obvious debt to Rampo Edogawa’s berserk tales of crime, revenge, and all-around freakishness. The Crawford style, which dominates The Living Skeleton from Saeko’s introduction until the death of Ono, is the bigger draw for me. He’s one of my favorite late-Victorian authors, but the closest thing I know of to a feature-film adaptation of his work is The Screaming Skull, which bears its putative source no resemblance of any kind. The Living Skeleton doesn’t plug that hole in the strict sense, of course, but for roughly half its length, it’s just Crawford’s type of somber and melancholy meditation on the loneliness of the coast, the impersonal hostility of the sea, and the capacity of each to create an environment more welcoming to the restless dead than to anyone whose heart is still beating. The specific supernatural manifestations are decidedly Crawfordesque, as well: a workaday ship seemingly returned from Davy Jones’s Locker, a woman who should have gone down with the vessel in question, the inanimate yet somehow still deadly bones of its murdered crew. The gorgeous black-and-white cinematography dovetails perfectly with this half of the subject matter, too, leaving the viewer feeling chilly and damp, while simultaneously counteracting the risible amateurishness that hampers even the simplest of The Living Skeleton’s special effects. (Perversely, however, the most complex one is a resounding success!) The titular bags of bones may look like something that a Mexican abuelita would hang up around the house on November 1st, but it almost doesn’t matter the way director of photography Masayuki Kato shoots them.

As the film wears on, though, and as the Dragon King conspirators draw more and more attention away from Saeko, Mochizuki, and Akashi, the Crawfordesque spookery increasingly recedes behind a scrim of noirish grit, underworld sleaze, and amorality. This second milieu— one of seedy nightclubs, retired assassins, drunkenness, gambling, and infidelity— is not a fit home for ghosts at all, so in a cockeyed way, it’s appropriate that there turns out to be a purely human vendetta behind the supernatural activity. The Living Skeleton doesn’t have a Scooby Doo ending, exactly. The ghosts and whatnot are real, but they’ve been conjured up by mad science rather than magic, and they act at the behest of an insane antihero whose continued existence on the mortal plane is not so much as suggested until the very climax. Strictly on its own terms, this other side of the film, which I attribute to the influence of Rampo Edogawa, and to his continuing domestic popularity, is every bit as effectively realized as the first. Suetsugu and the others belong to the breed of creeps that populate Kinji Fukusaku’s gangster movies, and it’s good fun watching them get bent further and further out of shape by a threat that can’t be answered with bullets or blades. Then the reintroduction of Tanuma, and his revelation as a bastard on an altogether higher level than his erstwhile accomplices, made for an escalation that I didn’t see coming at all (although naturally I knew the scar-headed ringleader from the mutiny prologue had to be waiting in the wings somehow). It’s merely that the movie’s two aspects are tonally at odds with each other in a way that director Hiroki Matsuno never manages to reconcile. Especially once the Dragon King entered the story for the third and final time, I was too caught up asking, “Where the fuck did this come from?!” to give what I was watching the appreciation that it truly deserved.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact