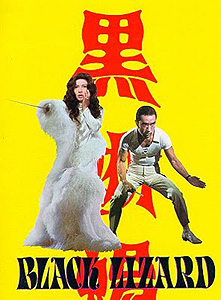

Black Lizard/Kurotakage (1968) ***

Black Lizard/Kurotakage (1968) ***

Sometimes it’s a struggle to find an appropriate lead-in to a review. With Black Lizard, the problem is that there are too many fruitful angles to pursue. Do I begin with Rampo Edogawa, an enormously prolific and popular Japanese author all but unknown in the West, whose writings inspired some of the strangest horror, mystery, and suspense movies of the 50’s and 60’s (Black Lizard among them), and whose penname becomes a bizarre bilingual pun when read in the family-name-first order traditional in Asia? Or do I start with Yukio Mishima, the adaptor of the stage play from which Black Lizard was immediately derived and a descendant of samurai, whose tireless (and simultaneous) crusades to win greater acceptance for homosexuals and to promote extreme right-wing political ideals made him one of the most controversial figures in postwar Japan right up until the day he committed seppuku after a failed attempt by his private army to seize control of a military base in 1970? Or perhaps with Akihiko Miwa, the notorious female impersonator who plays the title role? What about starting with Kinji Fukasaku, the director who did for the yakuza movie what Sergio Leone did for the western, but who is best known in the US for a pair of highly anomalous and extremely strange sci-fi movies, and for the Japanese segments of the Pearl Harbor dramatization, Tora! Tora! Tora!?

Actually, I don’t think I’m going to start with any of those guys, but rather with Umeji Inoue. Inoue was the relatively undistinguished director who first brought Edogawa’s Black Lizard to the screen for the Daiei studio (home of Gamera) in 1962. Inoue’s version has never been released in the English-speaking world, but those few descriptions of his version I’ve been able to turn up mostly paint it as a sort of Asiatic Sherlock Holmes and the Spider Woman, an anachronistic and lumbering failure of a suspense film. (And yes, it does indeed annoy the hell out of me that I was not able to get my hands on a copy so that I could find out for myself and review it before tackling the better-known remake.) Nobody ever says any such thing about the version which Kinji Fukasaku made for Shochiku six years later, however. If the Inoue Black Lizard was Sherlock Holmes and the Spider Woman, Japanese-style, then Fukasaku’s version is The Abominable Dr. Phibes as directed by John Waters circa 1981.

A well-dressed man (Isao Kimura, from The Seven Samurai and Lone Wolf and Cub: White Heaven in Hell) arrives at an isolated mansion by night, having learned of a secret nightclub in its basement. The man is ace private detective Kogoro Akechi (Akechi was to Edogawa what Sherlock Holmes was to Arthur Conan Doyle), and his reason for visiting the club is that he believes it to be owned by the Black Lizard, the master criminal whom he is currently pursuing. And God knows only an evil genius would want a place like this in their basement— picture the nightclub scene from Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, only without the fish heads, and you’ve got the thing nailed. While he’s casing the joint, Akechi spies a man some years younger than him (Yusuke Kawazu, from Genocide and Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla) drinking himself stupid on the far side of the room. A glamorous, 35-ish woman (Akihiko Miwa, whom Fukasaku would direct once more— in another drag role, as if that needed mentioning— in Black Rose the next year) comes over and says a few words to the drunk right before he passes out. The next day, Akechi reads in the newspaper that musician Jun Amamiya committed suicide during the night; the photograph accompanying the story depicts the hard drinker the detective saw at the Black Lizard’s club, and a visit to the morgue turns up the startling fact that Amamiya’s body has gone missing, the only clue to the disappearance the carcass of a small, black lizard which somebody left at the scene.

A bit later, in Osaka, Akechi meets with his current employer, Shobei Isawa (Junya Usami). Isawa is an extremely wealthy businessman, and he has recently received a series of anonymous letters threatening the kidnapping of his teenage daughter, Sanaye (Kikko Matsuoka, from The Living Skeleton and Trapped: The Crimson Bat)— supposedly, the kidnapping is going to take place at the stroke of twelve that very night, and Akechi plans on standing guard in the Isawas’ hotel room to make sure that no such thing can happen. For what it’s worth, Isawa himself believes that the planned abduction is only the first stage of something bigger, and that the kidnappers ultimately intend to use Sanaye to ransom the Star of Egypt, a ¥120,000,000 diamond which is well known to be the tycoon’s most valuable possession. But while the detective is discussing strategy with her father, Sanaye herself is in the lounge up on the top floor of the hotel, and she has just been accosted by the same woman Akechi saw at the secret club that night— and something tells me it’s of considerable importance that the woman sports a tattoo of a black lizard on her arm. Hey, whoever said an arch-criminal had to be a guy? Worse yet, she’s soon joined in chatting up Sanaye by the supposedly dead Jun Amamiya, and the two of them convince the girl to come down to Amamiya’s room to have a look at some kind of exotic doll. What Sanaye gets instead is a look at the inside of a chloroform-soaked rag, after which the Black Lizard has Amamiya strip her naked and lock her up in a gigantic trunk. By 9:30 pm, Amamiya and the trunk are safely on a train, speeding off to wherever Black Lizard HQ is, and there’s a life-sized automaton “asleep” in Sanaye’s bed in the hotel room. Then the Black Lizard swings by the Isawa pad herself to make time with Akechi and to gloat over her triumph when midnight rolls around, and the detective sees what that lump in Sanaye’s bed really is. The thing is, Akechi is at least as clever as the Black Lizard. Not only does he know who she is, he also spotted Amamiya at the hotel earlier, and sent some of his men to trail him. They saw what happened to Sanaye, and they were able to follow Amamiya onto the train, and to get the trunk containing the girl away from him (although Amamiya himself escaped). Indeed the Black Lizard herself only narrowly gets away from Akechi come midnight, having pocketed the detective’s pistol from his jacket while he had his head turned away. Needless to say, this isn’t over yet.

Back home in Tokyo, Isawa has learned well the lesson of his daughter’s close call in Osaka, and has turned his mansion into a veritable fortified compound. He has replaced his former staff of servants, and doubled the size of his retinue by adding a motley mob of shit-kickers led by an ex-cop named Matoba (Ko Nishimura, from Lady Snowblood and Gorath). And just to make sure we understand what a serious business this is, we get to see Matoba and his boys come within a hair’s breadth of roughing up a couple of delivery guys who have arrived unannounced with a living room set which somebody ordered but forgot to tell the guards about. All that preparation will avail Isawa nothing, however, for Hina, the new maid (Toshiko Kobayashi), and one of Matoba’s shit-kickers are secretly agents for the Black Lizard. They kill Matoba and arrange to have Sanaye smuggled out of the house inside the new sofa! (Looks like the guards were right to be suspicious of it…) Soon thereafter, Isawa submits to turning over the Star of Egypt in order to get his daughter back, but in the time that she’s had custody of the girl, the Black Lizard has reached some ideas of her own regarding what can and should be done with her. Luckily, Akechi is on the case once more, and again he proves that he and the Black Lizard are a very well-matched pair of adversaries.

It’s hard to know what to do with a story this outrageous. On the one hand, you could camp it up like crazy, but you could easily go too far in that direction and wind up with something like… well, practically every self-mocking horror, sci-fi, or adventure movie made during the last 25 years. Or you could try to keep a straight face, like Invasion of the Bee Girls, and run the risk that your audience will fail to get the joke. Fukasaku opts for a strange and not totally successful middle ground with Black Lizard, alternating fabulous excess with a form of restraint that is, in its own way, equally exaggerated. Just about all of the scenes set in one of the Black Lizard’s several lairs are as far over the top as a boundary-pushing director, a transvestite leading “lady,” and a gay, imperialist warrior-poet could make them, with garish sets, flamboyant costumes, and cartwheel-turning midgets all over the place. Akechi, on the other hand, is practically a caricature of the proper, straight-laced, and ultimately hypocritical Postwar Japanese Man, devoting every ounce of his energy and intelligence to combating the joyous revolt against conventionality that the Black Lizard represents, even as he secretly falls in love with her. Unfortunately, the increasingly numerous scenes in which the two antagonists must interact directly can’t be played both ways at the same time, and neither can most of them be played one way or the other without implicitly giving either Akechi or the Black Lizard the upper hand. Fukasaku’s answer— to play them no way at all— is thematically fitting, I guess, but it’s also dreadfully dull, weakening precisely those parts of the film that ought to be the most lively, as the irresistible force grinds against the immovable object. The only times when a meeting between the two foes works the way it should come when the situation permits or indeed requires one or the other of them to hold a temporary advantage, like the scene set in the stateroom of the Black Lizard’s ship, where she thinks she has Akechi trapped. So instead, we must watch Black Lizard for what surrounds the face-to-face feinting and parrying— for the nightclub scenes, the car chases, the revelation of the Black Lizard’s plan for Sanaye Isawa, the scenes in which Hina takes down her enemies by throwing constricting snakes at their necks from across the room. That stuff Fukasaku renders splendidly, with all the noise and bluster of a cheap comic book, and the fact that the female lead happens really to be a rather obvious man in drag just makes it all the more compellingly strange.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal tribute to Kinji Fukasaku. Click the banner below to see what my colleagues have to say on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact