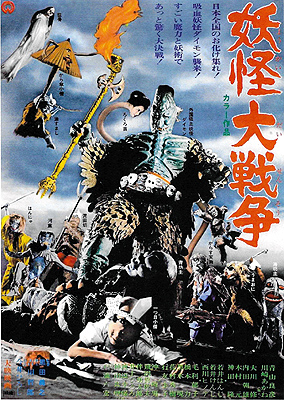

Spook Warfare / Yokai Monsters: Spook Warfare / Big Monster War / Ghosts on Parade / Yokai Daisenso (1968) ***˝

Spook Warfare / Yokai Monsters: Spook Warfare / Big Monster War / Ghosts on Parade / Yokai Daisenso (1968) ***˝

There’s an exception to pretty much every rule less rigorous than the second law of thermodynamics, so I guess it was bound to happen sometime. You know how I’m always going on about sequels released later the same year as their predecessors being invariably awful? Well, here’s one that’s not merely good, but actually better than the movie it followed! 100 Monsters was a nifty little film, but it was also an unfocussed and confused one, whose creators seemed not to understand fully whence its true appeal derived. While the yokai themselves, unusually enough, were the real heroes of the piece, neither writer Tetsuro Yoshida nor director Kimiyoshi Yasuda acted as though they fully understood that; they kept taking time away from the monsters and devoting it to a sturdy but pedestrian chambara plot about an imperial agent undercover as a ronin investigating the same corrupt official whom the yokai were pursuing for reasons of their own. Spook Warfare, the earlier of 100 Monsters’ two sequels, is an altogether more self-assured take on the material, with the yokai moved front and center where they belong. There’s a major difference of tone, too, for whereas the inaugural film in the series was very much a horror movie despite its frequent excursions into samurai melodrama and its atypically positive attitude toward monsters, Spook Warfare is more a darkly whimsical fairy tale in which even the most frightening and repellant of yokai are simultaneously figures of fun.

We begin in just about the last place you would ever expect to see as a setting in a yokai movie: 19th-century Mesopotamia! More specifically, we see the ruins of a Babylonian city (although the production designer seems to have confused Babylonia with Egypt, iconographically speaking), which a voiceover identifies as the place where “a violent monster” lies imprisoned. The voiceover then goes on to explain that an ancient prophecy warns of the monster’s release after a period of 4000 years, and I’m thinking the two treasure hunters in Arab garb who come along at that point are destined to act as its parole board. Now obviously this is just a coincidence, given both the timing of the two movies’ releases and the extremely narrow circulation that Spook Warfare originally received in the United States, but to a present-day viewer, this sequence looks a great deal like the prologue to The Exorcist. That resemblance becomes truly uncanny in a most unexpected way when the treasure hunters find and meddle with an intricately decorated bronze scepter, and fulfill thereby their unwitting role in the prophecy. Tetsuro Yoshida (who wrote this sequel as well) may call the monster “Daimon” (Chikara Hashimoto, from Destroy All Planets and The Ghostly Trap), but look at this guy for a minute. Towering, armored bird-man who flies about in the belly of a thunderstorm and uses gale-force winds as his signature weapon? Operates out of a ruin in the Mesopotamian desert? Doesn’t get along (as we’ll soon see) with other supernatural beings, even when they’re as evil as he is? Yeah, “Daimon” is as close as you can come within the limits of late-60’s Japanese monster-suit technology to Regan MacNeil’s old buddy, Pazuzu!

Anyway, it must be even more boring than it sounds to spend four millennia cooped up inside your own magic scepter, because Daimon doesn’t hang around his traditional stomping grounds for more than the moment it takes him to thank the treasure hunters for their assistance by burying them both alive in a cave-in. He immediately gathers up a storm and heads off exploring down the Persian Gulf, across the Indian Ocean, and into the Western Pacific, finally making landfall in, of all places, the town where the imperial magistrate for the Japanese province of Izu makes his home. The magistrate in question, Lord Hyogo Isobe (Takashi Kando, from 100 Monsters and Invasion of the Neptune Men), is out at the shore with his daughter, Lady Chie (Akane Kawasaki, of Nagasaki Women’s Prison and Eros Nights in Tokyo), and some of his retainers when Daimon’s storm rages through, and Isobe stays behind to secure the fishing gear while his companions hurry home. Seeing a lone human— even a well-armed samurai— tempts Daimon down to Earth, where he overcomes Isobe, feasts on his blood, and possesses his dead body to facilitate going abroad in this unfamiliar land. It would appear, however, that holiness remains holiness regardless of time or place, because the first thing the disguised Daimon does upon entering the magisterial palace is to demolish the household shrines to both Buddha and the Isobe family’s patron god, after which he orders the wreckage taken out and burned. Lady Chie is frightened and mystified by her father’s sudden impiety, and Isobe’s right-hand man, Saheiji Kawano (Gen Kimura, from The Tale of Zatoichi and Sleepy Eyes of Death: The Chinese Jade), agrees to see if he can’t talk some sense into His Lordship. That accomplishes nothing but to get Saheiji killed and possessed, too, so that the steward returns from his one-on-one chat with Isobe seemingly as mad as his master.

The palace has a more hands-on patron than the household god, however. In the main garden, there is a pond for koi, and in that pond dwells a kappa (Gen Kuroki, of The Haunted Castle and Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo)— a sort of anthropomorphic turtle with a hollow head full of enchanted water. The kappa considers the magisterial palace and its grounds to be his turf, and any supernatural being who messes with Isobe and his family will have to answer to him! Yeah, well a kappa is no match for the devil-god of the southwest wind, and the yokai quickly finds himself ousted from his own pond. Dejectedly, he makes his way to a set of overgrown ruins on the outskirts of town, which is haunted by a clique of spooks led by an abura sumashi, or “oil presser.” (This stumpy, stone-headed runt might be played by Hideki Hanamura, but that’s just a guess based on billing order.) Some of the denizens of the ruins we’ve seen before: the disturbingly sexy, stretchy-necked rokurokubi (Ikuro Mori, from Zatoichi’s Flashing Sword and Sleepy Eyes of Death: Full-Circle Killing) and the karakoso obake umbrella goblin (which is practically the official mascot of Daiei’s yokai trilogy). But there are also two new ones which I haven’t even managed to identify. One of these is an adorably disgusting walking meat-blob, while the other is a cute and perky girl (Keiko Yukitomi) with a grotesque second face on the back of her head. The kappa tells his fellow yokai all about getting evicted from his home by a strange monster, but they all think he’s pulling their legs. After all, the oil presser has copies of both the Pictorial Dictionary of Apparitions and the Apparition Social Register (at least the former of which seems to be a real book), and neither tome mentions anything like a giant, blood-drinking, corpse-possessing bird-man with weather-control powers. (Now if one of the yokai had thought to look in the Monster Manual II, it would have been a different story…)

The kappa’s friends begin to take his tale seriously only after Daimon sends Isobe’s retainers out into the community to round up more people whose blood he can drink. Anybody’s will do, really, but what Daimon particularly wants is the blood of children. The ones he tries to collect in the guise of Saheiji get away from him, though, and take refuge in the haunted ruins on the theory that not even a samurai wants to tangle with ghosts and monsters if he can help it. The kids explain, upon meeting the spooks, that the magistrate has changed without warning from a kind and benevolent ruler to a literally bloodthirsty tyrant, and although they don’t mention Daimon (whom they’ve seen only in the form of the magistrate’s steward), the oil presser and his friends are quick to notice that their story seems to corroborate the kappa’s. Then two more beings of the spirit world arrive on the scene (the dialogue identifies them as Aobozu [the Blue Priest] and Ungaikyo [which is what you get when a mirror comes to life on the hundredth anniversary of its creation], but they look nothing like either of those creatures as I’ve ever seen them described), not just with confirmation that there’s a new monster in the neighborhood, but with the lowdown on who and what the interloper is; one assumes these two get around more than the creatures who inhabit the ruins. Aobozu and Ungaikyo even know Daimon’s name. The yokai quickly decide that it would be an intolerable loss of face for them to let a foreign monster come to Japan and push the locals— human or supernatural— around, and after scaring Isobe’s forces away from the ruins, they take it upon themselves to show Daimon who’s boss.

Meanwhile, back at the palace, Lady Chie and the rest of the household grow increasingly frantic over their lord’s alarmingly uncharacteristic behavior. Fretting turns to terror when Chie’s handmaid, Shinobu (Hiromi Inoue), turns up dead and completely drained of blood. The condition of the body leads Shimpachiro Mayama (Yoshihiko Aoyama, from Daimajin and the fifth version of The Ghost of Yotsuya), one of Isobe’s samurai, to suspect that the problem is more than natural in origin. Luckily, Shimpachiro’s uncle (Asao Uchida, of The Living Skeleton and Sister Street Fighter) is a rather fierce Buddhist monk, and the samurai risks leaving the palace to enlist the old man’s aid. Shimpachiro’s uncle does indeed come through with knowledge of how to fight whatever is posing as Isobe. He gives Shimpachiro charms that should be able to restrict the demon’s movements, together with a set of candles that serve as the targeting system for the spiritual equivalent of nuking the site from orbit. The monk, obviously, will be the one to actually cast that powerful spell. He also advises Shimpachiro that blinding Isobe’s corpse will drive the demon out of it. Unfortunately, however, monk, samurai, and yokai alike have vastly underestimated Daimon’s power; defeating him will require a joint forces operation unprecedented in the history of mortal-monster relations.

It’s been a while since I last saw a fantasy movie as utterly charming as Spook Warfare. With its unrivalled menagerie of peculiar creatures, its cleverly accessible use of folkloric detail, its lighthearted approach to some fairly dark material, and its uniquely Japanese notion of monster jingoism, this film accomplishes a second time its predecessor’s most impressive feat— it isn’t like anything else I’ve seen before, 100 Monsters included. I love the off-kilter sense of humor (the quality perhaps most conspicuously lacking from the first film in the series), which combines with the endearingly crude yet weirdly convincing monster designs to suggest a Muppet movie directed by Frank Henenlotter after an extended vacation in Tokyo. I love the tighter integration of the human-centric and monster-centric plot threads, which indicates much more strongly than anything in 100 Monsters that the natural world and the supernatural one have a long-established modus vivendi. I’m especially fond of the inventive and often comical use this movie makes of the yokai’s vulnerability to the protective magic that the human heroes keep using to limited effect against Daimon. Seriously, these poor critters take more friendly fire than the Canadian Light Infantry at Tarnak Farm! There’s so much right with this movie that its relative obscurity outside its country of origin becomes truly mystifying. In particular, I can’t believe that Spook Warfare wasn’t picked up at once for American daytime television, because it has “instant kiddie matinee favorite” written all over it. Eight-year-olds wouldn’t have cared that they’d never heard of stretchy-necked ghost women or pot-bellied opossum-looking things whose paunches turn into magic television sets whenever they hold their breath; in fact, the way I remember it, encountering crazy shit you never knew existed was at least 60% of the thrill of childhood. I can easily imagine fervent schoolyard scenes in which the one kid who happened to catch Spook Warfare on the Zombilina show last Saturday mesmerizes all his friends with a breathlessly recited play-by-play: “And then the girl turned around, and she had another face on the back of her head! And that face had a tentacle where the nose was supposed to be, and there was a hand on the end of it!” Admittedly, today’s professional worrywarts would no doubt find all kinds of things to take exception to about this movie, but Spook Warfare strikes me as no more ghoulish than Gamera vs. Gaos, which suffered little disfigurement on the journey from Japan’s big screen to our little one. Spook Warfare was even made by the same studio as the Gamera series, so we seemingly can’t attribute its failure to achieve Stateside distribution outside of neighborhood theaters in Japanese immigrant enclaves to distributor ignorance or lack of transoceanic market penetration on Daiei’s part. Well, whatever. You can see Spook Warfare now, via the AD Vision DVD, and if a description like “Nightbreed for kids” exerts any pull at all on your imagination, then you really owe it to yourself to do so.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact