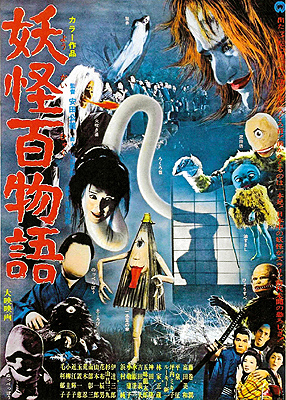

100 Monsters / Yokai Monsters: 100 Monsters / Yokai Hyaku Mongatari (1968) ***

100 Monsters / Yokai Monsters: 100 Monsters / Yokai Hyaku Mongatari (1968) ***

It’s really odd, when you think about it, what short shrift Western horror movies have given over the years to Europe’s enormously rich tradition of myths and folktales concerning monsters and supernatural beings. Only a few privileged representatives of the West’s vast legendary bestiary— most notably vampires, werewolves, and the Devil— have logged very much fright-film screen time, and even then the treatment they receive generally owes more to literary antecedents than to anything told and retold for centuries around campfires and over the beds of children having a hard time falling asleep. Sure, our makers of fantasy adventure movies have gotten some mileage out of goblins, dragons, cyclopes, and the like, but that’s different. No one’s really supposed to be scared of the monsters in Jason and the Argonauts or The Magic Sword. Casual fans might be forgiven for assuming that a similar state of affairs exists the world over as well, but do not be deceived by the vagaries of international licensing agreements. Other cultures have been much readier to mine their age-old spook and monster stories for horror film premises, but the resulting movies generally received little if any exposure outside their home countries until fairly recently. K. Gordon Murray imported scads of Mexican vampire flicks for broadcast on American television, for example, but of the similarly numerous Llorona movies, only The Curse of the Crying Woman ever made its way north of the Rio Grande except in untranslated bootleg form. Such selectivity was perfectly reasonable in the days of monolithic mass popular culture, too— The Vampire’s Coffin would be instantly comprehensible to anyone acquainted with Dracula, but would-be distributors of La Llorona would have quite a bit of explaining to do for the benefit of non-Mexican audiences. It’s been a decade and more, though, since any such “one size fits all” pop culture existed in much of the developed world, and one of the cool things about that splintering of the consumer base into a thousand little niche markets is that it now makes equally sound business sense to revive some of the more intensely idiosyncratic Asian, Latin American, and indeed African horror films for an audience that specifically craves the bizarre, the exotic, and the unfamiliar. Which brings us at last to 100 Monsters, the first in a three-picture series from Japan’s Daiei studio, and easily one of the most particularly Japanese fright films ever made. In the late 60’s, 100 Monsters could secure only a handful of brief bookings in American theaters, and then only in the ethnic enclaves of cities with large Japanese immigrant populations. By 2003, however, 100 Monsters and its sequels looked like good enough risks for longtime anime importers ADV Films to release them in lovely widescreen, subtitled DVD editions. (Curiously, the ADV Films DVD bills 100 Monsters as Yokai Monsters, Volume 2, with the first sequel, Spook Warfare, getting the Volume 1 slot. Spook Warfare seems to enjoy the most favorable reputation of the three films, so it may be that ADV’s planners figured it made better financial sense to reorder the series and come out swinging.)

So what exactly is a yokai? So far as I can tell, the term is applicable to just about every supernatural critter of less than godly power recognized by Japanese folklore and mythology, with the possible exception of various formerly human beings roughly analogous to what Westerners think of as ghosts. Everything from the oni mountain-ogres to shape-shifting animals to inanimate objects that come to life on the hundredth anniversary of their creation qualify as yokai, and if there’s any unifying characteristic that applies across the whole category, it’s a tendency toward irascible dispositions running the gamut from tricksterish mischievousness to a violent dislike for humans. Yokai, in other words, are the kind of things you want to avoid altogether if possible, and to ward off or placate otherwise. And naturally, they’re also a popular topic for storytellers, as we see when 100 Monsters opens with a man entertaining a small crowd with the tale of his own encounter with a tsuchikorobi, a faceless creature made of dirt and hair that waylays travelers by bunching itself up into a ball and rolling after them at high speed. The occasion for this recitation is a social event called the hyaku monogatari, or 100 stories. Basically, a bunch of people gather in a candlelit chamber and tell a spook story each, extinguishing one of the candles at the end of each tale until the room is in total darkness. Perhaps on special occasions, the hyaku monogatari really would involve a literal hundred stories, but it’s worth bearing in mind that hyaku is also used figuratively to mean “a lot” or even “every.” But for our present purposes, the really salient point about the hyaku monogatari tradition is that the telling of the final story is always followed by a curse-dissipating ceremony, to prevent any of the malign beings discussed in the various tales from manifesting themselves to haunt either the venue or the participants. (100 Monsters doesn’t mention this, but some versions of the tradition have it that an unsanctified hyaku monogatari attracts a specific yokai of its very own, a sort of demonic patron of the arts called the ao andon, or blue lantern spirit.) The film makes a big deal out of the de-cursing that follows the tsuchikorobi story, so it’s a safe bet that something similar is going to be of paramount importance later on.

In the meantime, let’s get acquainted with Tajimaya (Takashi Kanda, from Prince of Space and Wrath of Daimajin), the wealthiest resident of whatever Edo-period riverside village this is supposed to be. Tajimaya apparently made his fortune in the shipping business, and did well enough for himself that he now controls a fleet of ten vessels. He’s also a conniving bastard, and he has his eye on a choice plot of land currently occupied by a dilapidated but still much-respected shrine and the boarding house wherein dwell seemingly all of the village’s single women. The two lots currently belong to a man of otherwise very modest means, by the name of Jinbei (The Snow Woman’s Tatsuo Hananuno), and Tajimaya has rigged it so that Jinbei owes him a significant amount of money— more than he is strictly speaking good for without putting up the shrine and the boarding house as collateral. You see where this is going, right? One morning, when Gohei the caretaker (Jun Namamura, of Kwaidan and The Vampire Doll) sets off on his daily rounds, he finds Tajimaya’s head flunky, Jusuke (Yoshiro Yoshida, from The Swamp and Gamera vs. Zigra), standing outside the shrine with a mob at his back. Jusuke announces that Tajimaya is taking possession of the land, with the aim of demolishing both currently extant buildings and erecting a lavish whorehouse in their place. Naturally, the news goes over poorly with Gohei, Jinbei, and Jinbei’s numerous tenants, and tempers flare so hot that Gohei attacks Jusuke’s bruisers. While I’m quite certain that getting beaten to death wasn’t exactly what the old caretaker had in mind, Gohei’s manslaughter does at least get everyone involved on both sides sufficiently freaked out to withdraw from the site of the clash for regrouping and rethinking their respective strategies.

Now it often happens that people like Tajimaya are merely the instruments of even bigger and fouler slimeballs, and indeed that is the case here. The man pulling Tajimaya’s strings is Lord Uzen of Hotta (Ryutaro Gomi, from Sword of Vengeance and Zatoichi’s Flashing Sword), the local imperial magistrate. Uzen is the authority whose say-so is required for the closing or repurposing of a shrine, and although this is never made explicit, it’s a safe bet that Tajimaya is going to be cutting him in for a share of the profits once his whorehouse is up and running. The magistrate comes to visit on the evening after Jusuke’s unsuccessful effort to oust Jinbei and his tenants, and following through on the opening scene’s foreshadowing, Tajimaya decides to go all-out on the entertainment by staging a hyaku monogatari for the amusement of Uzen and his retainers. Uzen, inevitably, doesn’t go in for all that curse claptrap, and insists on bringing the evening to a close by handing out a round of massive bribes rather than with the traditional ceremony of benediction. That leads with equal inevitability to the magistrate, his household, and everyone on his payroll having encounters with a whole menagerie of freaky supernatural creatures— ranging from the faceless noppera-bo doppelgangers that start terrorizing Jusuke, to the sky-eclipsing Cackling Woman who panics two of Tajimaya’s lieutenants into killing each other, to everybody’s favorites, the karakoso obake umbrella goblins that befriend Tajimaya’s retarded son (Rokie Shinichi) and incite him to do things calculated to embarrass his old man in front of Uzen. And as if that weren’t trouble enough for Uzen and his fellow schemers, the somewhat withdrawn and seemingly shiftless guy who is the only man staying at Jinbei’s boarding house (Daimajin’s Jun Fujimaki) is really an undercover agent for the imperial government, who has been sent to investigate rumors of corruption surrounding the magistrate.

If, as I said before, you’re craving the bizarre, the exotic, and the unfamiliar, 100 Monsters is as good a way to seek satisfaction as any. I can think of nothing truly comparable in all of Western cinema, and this movie is astonishingly well made considering that the studio responsible for it is best known as the company behind the endearingly dumb Gamera series. Viewers accustomed to floppy-jawed turtles with ping pong balls for eyes and shoddy giant steak-knife lizards will be blown away by the crude but effective yokai of 100 Monsters, and so far as I’ve seen, its pervasive dream-world atmosphere is matched among contemporary Japanese films only by Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell— which was an avowed attempt to duplicate the style of dream-atmosphere grandmaster Mario Bava. The acting, to the extent that it can be judged by someone who understands as little Japanese as I do, seems a bit forced and unnatural, but in a way that suggests deliberate stylization more than mere incompetence. And yet for all its unexpected quality, 100 Monsters maintains a sense of fun not too far removed from that of Daiei’s kaiju and sci-fi movies. A comparison between 100 Monsters and Toho’s slightly earlier (and much more expensive) Kwaidan is instructive here. Whereas Kwaidan often seems to be inhibited and intimidated by its own prestige, the makers of this film display a confident willingness to look absurd, with the paradoxical result that even its goofiest moments come off well. Shinkichi Tajimaya’s introduction to the umbrella goblins stands out as a case in point. The first such creature appears to him when, inspired by the painted screens brought out to decorate his father’s parlor for the hyaku monogatari, he draws a picture of a karakoso obake on his bedroom wall. The drawing comes to life in stages, initially as a two-dimensional cartoon, and then as the delightfully weird puppet that is easily the most frequently encountered image from the Daiei yokai trilogy. It sounds ludicrous— and it looks ludicrous, too, in those oft-reproduced production stills— but in context, it’s a bewitching scene.

Where 100 Monsters goes a bit wrong is on the story-structure front. Simply put, there isn’t quite enough room in this tale for both an army of spooks and an undercover imperial agent on the hunt for institutional wrongdoing, and trying to accommodate both costs the movie dearly in focus and coherence. The scenario of corrupt official vs. heroic ronin (who may or may not be an official himself operating incognito) is a mainstay of the chambara genre of period martial arts melodramas, much as it is (with a certain amount of cultural transposition, obviously) in the Chinese wuxia swordsman movies of the same era. With Yatsutaro the undercover samurai pursuing Lord Uzen’s downfall in parallel with the things that go bump in the night, 100 Monsters tends to convey the counterproductive impression of a standard but serviceable chambara being hijacked by mischievous yokai every time the plot starts to get really rolling. It would have been better, in my opinion, to ditch the human good guy altogether, and to acknowledge openly that the monsters themselves are the heroes of the film. As it stands, Yatsutaro is constantly having his job done for him, leaving him with very little scope of action outside of serving as a love interest for Jinbei’s daughter, Okiku (Miwa Takada, from Zatoichi the Fugitive and Sleepy Eyes of Death: Sword of Adventure). The other major defect arises solely on the ADV Films DVD, where the subtitles leave a great deal to be desired. They remind me a lot of the more accomplished anime fan-subs I’ve seen, with translations that sound more or less accurate, but also artlessly clunky— almost as if you were watching the film with the aid of an interpreter. 100 Monsters would benefit greatly from a more elegant and euphonious rendering of its dialogue.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact