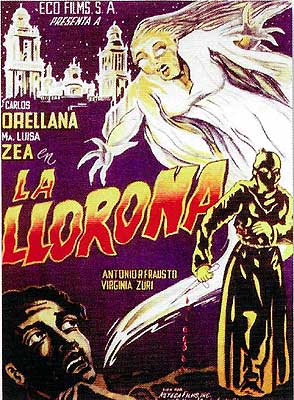

The Crying Woman/La Llorona (1933) **½

The Crying Woman/La Llorona (1933) **½

I’m pretty sure it was from David J. Skal’s The Monster Show that I first learned of a Spanish-language version of Dracula made in parallel with the one we all know. That would have been in the early 1990’s, when there was precious little prospect of actually seeing the thing, so I just sort of filed the information away without thinking too much about it. I didn’t really consider how or where such a film would have been distributed, and I certainly never took up the question of what impact it might have had wherever it was originally shown. That seems an embarrassing omission in retrospect, because this is frigging Dracula we’re talking about! Tod Browning’s version revolutionized American horror cinema; what might its Spanish-speaking doppelganger have wrought south of the border? Well, truth be told, the timing is far enough off that I can’t confidently pin this on Dracula, or still less on La Voluntad del Muerto (Universal’s slightly earlier Spanish-language export version of The Cat Creeps), but the fact remains that Mexico enjoyed a largely forgotten boomlet in horror movie production during the 1930’s. To be sure, it was nothing compared to the tidal wave of fright films that hit Mexican theaters in the 50’s, when masked wrestlers began battling Martians, mummies, and mad scientists, and vampires lurked behind every tombstone. But it was nevertheless a phenomenon worthy of note, and the picture that kicked it off, The Crying Woman, unmistakably does owe something to the example of those visitors from el Norte.

At the same time, though, The Crying Woman displays a commendable independence with regard to subject matter. La Llorona hasn’t had much exposure abroad, but she’s one of Mexico’s most venerable native spooks, with a tradition reaching back centuries. Naturally, her legend has developed its share of contradictions over all that time, but at bottom, la Llorona is a bit like the banshees of Ireland: a spectral woman whose incessant weeping is at best a harbinger of death or misfortune for anyone who hears it, and at worst supernaturally lethal in and of itself. Her mutable origin story makes her variously the scorned mistress of an unscrupulous patron, a desperate widow who commited a heinous crime out of misguided love, or a Nahua princess driven to suicide by the cruelty of the conquering Spaniards. Her ever-shifting modus operandi lets her function as a bogey for scaring wayward children, as a cautionary example for women too strongly governed by their passions, and even as a nationalistic avenger, hounding the descendants of conquistadors through history. And sometimes she has a horse’s head. Because why not, right? La Llorona has become a fixture of horror cinema in her home country, so it’s fitting that her film debut should also mark the local advent of the entire genre. And since this is la Llorona’s first film appearance, it’s equally fitting that screenwriters A. Guzman Aguilera, Carlos Noriega Hope, and Fernando de Fuentes sorted out the conflicting versions of the legend in the way that they did. They attempted to reconcile all of them (or at least all of them that didn’t require a horse’s head), while simultaneously throwing in as many gringo spooky house tropes as could be made to fit, and anticipating the science-vs.-superstition theme that would loom so large in the 1950’s.

You see that drunken lout rolling himself a cigarette outside the cemetery gates a moment before midnight? Yeah, well don’t get too attached to him. In fact, don’t even bother asking his name. The instant the church bells finish tolling the Witching Hour, an unearthly shriek rings out, and the drunk collapses onto the pavement, stone dead. His body ends up in the morgue at the hospital where Dr. Ricardo de Acuna (Ramón Pereda, from The Macabre Trunk and The Sea Devil) works as a surgeon. Acuna shows off the corpse to a few of his students as a textbook case of cardiac arrest, waving away the dark chatter among them regarding rumors that the deceased was slain by a ghost. There’ll be none of that cago de toro in this hospital, damnit!

Okay— but how about in Acuna’s home? The doctor is married to a wealthy country heiress named Maria (Virginia Zuri), the daughter of Don Fernando de Moncada (Paco Martinez, from The Phantom of the Monastery and The Dead Speak). Ricardo’s son, Juanito, is about to turn four years old, and that has the old man worried. You see, the Moncada family is cursed. Don Fernando knows how that sounds, but he implores his son-in-law to hear him out. Consulting a volume on family history from the villa library, Fernando tells Ricardo about the last time the Moncada and Acuna lineages crossed paths. 300 years ago or thereabouts, Fernando’s ancestor, Don Rodrigo de Cortes (played in the ensuing flashback by Alberto Marti), was attacked by bandits and rescued by Ricardo’s ancestor, Captain Diego de Acuna (also Ramón Pereda). The soldier escorted Cortes home after driving off the ruffians, and ended up staying the night. Thus was Diego de Acuna introduced to, and instantly smitten by, Marina (She-Devil Island’s Maria Luisa Zea), Don Rodrigo’s mistress and the mother of his child. The couple had been together for more than four years, but Cortes would not marry Marina until he had attained some position of even greater wealth and power for which he was angling; he assured her that it was merely a matter of time, though. Rodrigo told Diego a very different story that evening, however, while Marina was putting their child to bed. It was true that Cortes was planning to marry soon, and that he was on the verge of attaining his political goal at last— but he was going to accomplish the latter by means of the former, wedding a well-connected lady and leaving Marina to fend for herself!

The scheme would have offended the captain’s sense of chivalry even if he hadn’t fallen in love at first sight with the woman his host was fixing to fuck over, and Acuna vowed himself to foil Cortes’s designs. When the time came, he crashed the don’s wedding with Marina and the child in tow, and exposed Cortes as a conniving two-timer in front of the bride, the bishop, and all the leading citizens assembled as guests. Rodrigo de Cortes would have his revenge, however. After the fiasco at the church, he tried to assert his paternal rights by taking his bastard son away from Marina. Rather than accept that betrayal, Marina killed both the boy and herself; denied entry into heaven for her crimes, she became the howling specter known as la Llorona. Some comparable tragedy has befallen every patriarch of the Cortes family line, too. Don Fernando himself lost his wife and son under circumstances he declines to describe when Maria was but an infant. Nor, for that matter, did the family curse begin with Don Rodrigo. Its true origin is recounted in a different old book, but Fernando can’t seem to locate it at the moment. He’ll have to get back to Ricardo on that. The point is, whatever doom is destined to befall the firstborn son of a Cortes (and the Moncadas are Cortes enough), it invariably occurs on or about the child’s fourth birthday. That is, if the old man knows what he’s talking about, Juanito is fated to die this very night!

Don Fernando never gets a chance to tell that other story he mentioned, though. His conversation with his son-in-law is eavesdropped on by a masked prowler in black monastic robes, hiding in a secret passage behind one of the bookcases, and that prowler springs forth to kill Fernando as soon as Ricardo (spooked despite himself) leaves to look in on his wife and son. What Fernando would have revealed is that the first Llorona was an Indian princess who was raped by the Cortes somewhere along his way to smashing the Aztec empire. When the girl gave birth, Cortes had the baby taken away from her to be raised as a Spaniard. The princess killed herself in despair (becoming a malign ghost in the process), and her people have hounded the conquistador’s descendants ever since, engineering retributive tragedies involving the death of wife and firstborn son in each successive generation. And unbeknownst to poor Don Fernando or his family, the household staff includes members of that avenging Nahua tribe. The latter would have preferred to maneuver Maria into an infanticide-suicide combo as per tradition, but they’ll settle for straight-up double murder if it comes to that.

The Crying Woman approaches its supernatural elements in a way that I don’t think I’ve ever seen before, splitting the difference between post-Dracula “authenticity” and the old “rational explanation” routine. The ghost is real— indeed four separate ghosts are real— but la Llorona is basically a red herring in all of her avatars. It isn’t spooks threatening the Cortes-Moncada family, nor is it a supernatural curse on their bloodline, but rather a good, old-fashioned feud prosecuted by the descendants of people whom they or their ancestors had wronged. And while I’m not convinced this part is deliberate, there’s room to interpret it as a commentary on colonial and post-colonial power structures when it becomes clear that Don Fernando and his forebears had simply never noticed that the help were gunning for them for 400 years. I also have to commend how well thought-out the artificial curse on the family is, at least within the context of a culture where large families and early marriages are the norm. Because the Nahua revenge cultists kill only the wives and firstborn sons of the Corteses, they effectively conserve the hated bloodline so that they can keep on torturing their enemies forever.

There is one major disadvantage, however, to treating the several Llorona legends as generational variations on a theme that runs across centuries. It compromises the unity of the film, because there are really three stories here, each with its own cast of characters working out their own conflicts. (For that matter, the opening scene with the dying drunk hints at yet a fourth story, since we never do learn where that Llorona came from.) Then on top of that, The Crying Woman is structured so as to be critically dependent on long, momentum-killing flashbacks, both of which come at what ought to be moments of high suspense. The first time it happens is forgivable, because the hooded prowler is merely spying on Don Fernando as he fills Ricardo in on half of the back story. It’s early in the film yet, and The Crying Woman can afford to put whatever the prowler is up to on hold for a bit of exposition. But the second flashback revealing the story of the ill-fated Nahua princess comes while Dr. Acuna and a squad of policemen (the latter summoned to the house upon discovery of Don Fernando’s body) are in hot pursuit of a murderer. Nobody is going to care about the origin of the first Llorona at that point, and it strains credulity to the uttermost to have the good guys pause in mid-chase to read from some old book which their quarry dropped in haste to escape. Even the old cliché of a post-capture “why I did it” speech from the villain would have been preferable.

On the other hand, there’s simply no faulting The Crying Woman on looks or atmosphere. The sets for the Moncada villa strike a believable balance between feeling spooky and feeling lived-in. The house is warm and welcoming inside, but also just a bit oppressive with the weight of its antiquity. Then of course there are the secret passages within the walls and the catacombs with which they communicate, known to the Nahua revenge cult, but forgotten by the villa’s owners. As befits the lair of a centuries-old evil, those tunnels form a dark and hostile underworld fit less for the living than for the angry and unforgiving dead. These environments are where the Universal influence is most strongly apparent. The architecture may be Spanish colonial instead of faux-Germanic, but the vibe is Expressionist-inspired gothic all the way. Also gothic— in an unexpectedly antique sense— is the character design for the killer stalking the house. Looking back from the 21st century, the hood-and-cassock combo suggests Krimi villains like the Black Abbott and the Monk with the Whip, but the intended reference is more likely to be the evil clergymen of Matthew Lewis, Ann Radcliffe, and the like. The hooded assassin’s modus operandi, meanwhile, derives mainly from still another source, the Colorful Killer school of spooky house mysteries. Those films contribute their signature visual cues to The Crying Woman as well. That strange recombinance is how this picture most conspicuously sets the precedent for future South-of-the-Border horror films, I think. Although The Crying Woman is altogether more staid and sober than one expects based on what came afterward, it displays the same willingness to raid anything and everything that foreign genre traditions have to offer, combining the borrowed elements with homegrown themes and subject matter to create a uniquely Mexican synthesis.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact