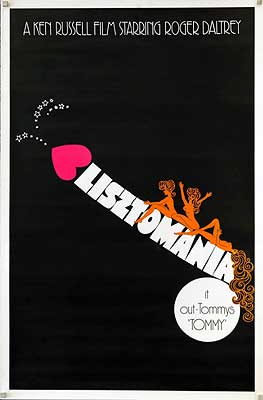

Lisztomania (1975) -***½

Lisztomania (1975) -***½

The trouble with a roundtable topic like “WTF?” is that that’s kind of what we B-Masters do already. From a civilian point of view, so to speak, something like Future Hunters or The Blood Waters of Dr. Z would be plenty weird enough to fit the bill. I mean, try bringing either of those to a party thrown by people from the office or yoga class or the karate dojo, and see how long it takes for rebellion to break out. I’d feel like I was cheating, though, if the screwiest thing I came up with for this event was a sullen prick trying to conquer the world by turning himself into a catfish— and I suspect you’d feel like I was cheating, too. Reviewers with the arrogance to call themselves “B-Masters” should hold themselves to a higher standard of “what the fuck?” than that. So instead, how about we crack open a nice bottle of 151-proof Ken Russell?

Russell spent the first half of the 70’s on a curious jag indeed. Although my regular readers will probably think first of The Devils in connection with this phase of Russell’s career, he really spent most of it as a sort of interpretive biographer. What I mean is that rather than just depicting the events of his subjects’ lives, even in dramatized or fictionalized form, Russell took an avowedly symbolic approach. Consider the climax to The Music Lovers, the Pyotr Tchaikovsky biopic from 1970 which initiated the whole cycle. The sequence represents the debut performance of the 1812 Overture, the piece that established Tchaikovsky as an international Big Deal, but don’t bother looking for orchestras or concert halls on the screen during most of it. Instead, Russell shows the composer running through the streets of a war-torn city, only to be seized and feted by an adoring crowd. His agents and managers, meanwhile, stand with bags open into the wind to catch the clouds of money billowing toward them on it. And as the overture reaches its crescendo, the famous rhythm-setting cannons literally blow the audience’s heads off in their seats. It’s clear enough what it all means, but it’s a jarring way to treat such respectable subject matter— albeit hardly more jarring than the rest of the film, which focuses on Tchaikovsky’s embattled homosexuality and his wife’s supposed nymphomania. Mahler upped the ante a few years later with a nominal flashback to that composer’s conversion from Judaism to Catholicism at the urging of Cosima Wagner, mounted as a riff on Paul Leni’s Siegfried in which a Nazi dominatrix incites Mahler to forge his Star of David into a cruciform sword, so that he may kill and eat a fire-breathing pig. But the screwiest of all Russell’s classical music biopics was Lisztomania, made in a frantic hurry to capitalize on the success of his film version of the Who’s rock-opera, Tommy.

In theory, Lisztomania concerns the life, career, and legacy of 19th-century Hungarian composer Liszt Ferenc, better known by the Germanized version of his name, Franz Liszt. But the way Ken Russell tells it, nothing makes a lick of sense unless you already know a fair amount of the story. Briefly, then: Franz Liszt was born on October 22nd, 1811, in an Austro-Hungarian town called Raiding. He was a child prodigy on the piano, giving his first public concert at the age of nine, but spent his whole life wobbling into and out of performing due to recurring bouts of illness and emotional turmoil. The adult Liszt was a musician of rare technical ability, a composer of widely proclaimed genius, an electrifying live performer, and a notorious womanizer. The title of Russell’s film was originally the name given by a bewildered musical press to the emotional effect Liszt evoked from his audiences— the female listeners especially. It would be neither unfair nor unreasonable to characterize him as the original rock star. Liszt’s personal life, meanwhile, sorts comfortably enough into four phases: a somewhat rudderless youth; a ten-year affair with the French countess Marie de Flavigny d’Agoult; a much longer romance with Polish princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Witgenstein, which was mortally wounded when Pope Pius IX refused to grant her leave to divorce her husband; and finally a withdrawal in the direction of Catholic monasticism (although Liszt never quite finalized his transformation into either monk or priest). Liszt fathered three children with Countess d’Agoult, one of whom, Cosima, successively married two of her father’s favorite protégés: Hans von Bülow and Richard Wagner. His final years were spent in ill health and depression, the two conditions no doubt intimately linked. He died of complications from pneumonia (possibly with a little help from medical malpractice) on July 31st, 1886. Most of that stuff is indeed to be found in Lisztomania, along with a bunch of other details too fiddly to be worth mentioning in such a quick rundown. It’s just that it’s all buried under psychedelic symbolism, visual metaphor, bizarre musical numbers, sheer sensationalism, and an openly fantastical final act in which Cosima and Wagner emerge as supernatural supervillains of anti-Semitism. Oh— and it’s buried under a ton of colossal prosthetic dicks, too.

All things considered, it seems fair enough that we meet Liszt (Who frontman Roger Daltrey, whose other acting gigs have included Vampirella and The Legacy) in bed with Marie d’Agoult (Fiona Lewis, of Tintorera and Inner Space), demonstrating his famous rhythm-keeping prowess by kissing her nipples in time to the metronome mounted on the nightstand. (Liszt always rehearsed with a metronome, and attributed his extraordinary sense of timing to that practice.) That’s not what Count Charles (John Justin, from Schalken the Painter and The Thief of Bagdad) hired him for, of course, so d’Agoult is most annoyed when he walks in on his wife, and sees what she’s up to with her ostensible piano tutor. The count engages Liszt in a duel on the spot— not how things are technically supposed to be done, but when have the niceties of chivalry ever extended to commoners? When Charles inevitably comes out on top, Marie valiantly insists upon sharing Liszt’s fate. The count wouldn’t have it any other way, really, and the two adulterers are swiftly entombed inside a grand piano, which d’Agoult and his lackeys leave on the nearest railroad tracks like a bunch of stereotypical silent serial villains.

Don’t bother asking me how Franz and Marie escape from that fix. Come to think of it, don’t bother asking Ken Russell, either. The next thing we know, Liszt is backstage at a concert hall in Bonn, where he’s about to put on a performance to raise money for a monument to the city’s favorite son, Ludwig van Beethoven. The green room is packed with celebrities from the world of the arts: composers like Hector Berlioz (Madhouse Mansion’s Murray Melvin), Felix Mendelsohn (Otto Diamant, from Blood of the Vampire and The Fearless Vampire Killers), and Frederic Chopin (Kenneth Colley, of The Empire Strikes Back and The Devils); author George Sand (Lair of the White Worm’s Imogen Claire, who has a similar small but attention-getting part as one of Dr. Furter’s party guests in The Rocky Horror Picture Show); dancer Lola Montez (Anulka Dziubinska, of Vampyres); and heaven knows who else. Also hanging around is a young musician named Richard Wagner (Paul Nicholas, from See No Evil and What Became of Jack and Jill?), who keeps pestering Liszt with the score to his newly completed opera, Rienzi. Liszt finally humors Wagner by looking the thing over, but you can practically see him counting the seconds until his sidekick, Hans von Bülow (Andrew Reilly), announces that it’s time to go on.

The ensuing show is sheer torture for poor Wagner. Liszt plays some selections from his opera, alright, but he keeps interweaving them with “Chopsticks,” which is what the screaming teenaged girls in the audience unanimously demand to hear. (I don’t know what to make of this “Chopsticks” business, incidentally. The piece wasn’t written until 1877— some 35 years after this scene appears to take place— and I can find no evidence of it ever being associated with Franz Liszt in any way. Perhaps it was simply the most banal thing Russell could think of that still technically counted as classical music.) Wagner eventually flees the hall in sheer embarrassment, after which Liszt turns his attention to the more serious business of selecting his next mistress. Still performing, he signals to Hans to inquire after this or that woman in the audience, and ultimately settles on Polish princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (Sara Kestelman, of Zardoz). The princess is a lucky break, because Liszt is due to play for the czar himself in St. Petersburg soon; now he’ll have a bedmate in the Russian Empire lined up ahead of time.

As you might have guessed, Liszt’s interest in Princess Carolyne means that his relationship with Marie d’Agoult has hit the skids. It was good while it lasted, mind you— so pure and innocent despite its adulterous origins that a flashback to happier days sets an arrangement of Liszt’s own Liebestraum (“Dream of Love”) to a riff on the romantic bits from silent comedies, with Daltrey tricked out as a fair approximation of Charlie Chaplin. The life of a touring musician is not conducive to settling down, however, even with three children in the picture, and Marie has gotten fed up with her boyfriend’s philandering on the road. Franz, meanwhile, is fed up with how the countervailing pressures of touring and family life leave him no spare brainspace to write new music in any serious way. As he tells his adolescent daughter, Cosima (Veronica Quilligan), he’d sell his soul to be able to write something really worthwhile again.

Luckily for Liszt, his soul is just what Princess Carolyne is looking to buy. The princess and her husband are separated, but because she’s the one with all the land and money, he’s in no hurry to grant her a divorce. Carolyne wants to pack up and flee to Paris before he can convince the czar to confiscate her estates, but she doesn’t want to do it alone. And as an artist herself (Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein was a heroically prolific author), she’d enjoy exile best in the company of somebody else creative, whose muse she could become. She’s going to be the one in charge, though, you understand. Princesses don’t take orders from anybody. Liszt’s acquiescence to his hostess’s plan takes the form of a musical number with a chorus line consisting of all his former lovers, in which Carolyne transforms into a dominatrix succubus and lops off his dick (engorged by that point to a length of roughly ten feet, and a foot and a half in diameter) with a guillotine. (In real life, Princess Carolyne did not hold a high opinion of human sexuality.)

Skipping ahead now to 1848, Liszt is living with the princess not in Paris, but in Weimar, and the Sayn-Wittgensteins are close to hammering out a divorce settlement. Franz has his writing mojo back, and plenty of time on his hands in which to exercise it. Just the same, he’s not happy. He’s always thought of himself as a proud Hungarian, but what is he doing while his people join in that year’s continent-wide epidemic of revolution and national uprisings? Sitting on his ass in complacent comfort, that’s what! Even that putz Wagner has shown more mettle. As the tide of unrest reaches Germany, Richard embraces both Communism and pan-German nationalism, making himself a wanted man. Mind you, Wagner also embraces vampirism, and the next time he drops in on Liszt, it’s to drink his blood, corrupt his music, and run away with his daughter. Also, Franz’s marriage to Carolyne isn’t nearly as done a deal as either of them thinks. The whole thing still requires the blessing of Pope Pius IX (Ringo Starr, from Caveman, Young Dracula, and the Beatles), who withholds it at the last minute on unexplained grounds. The lovers part amicably at that point, the pope’s action having rather taken the wind out of their relationship’s sails. Carolyne promises one of her trademark massively multivolume treatises against the church in retaliation, but Liszt’s revenge is more creative. He takes holy orders with the lay arm of the Franciscan Brotherhood, putting himself on the Holy Mother Church’s payroll.

Why remain among the laity when priests and monks get so much more respect? Because the laity get laid, of course. Liszt is doing just that with his latest mistress (Little Nell Campbell, from Summer of Secrets and The Rocky Horror Picture Show) when the pope sticks his miter into the composer’s business a second time. Pius is incensed about Wagner and Cosima, who are running around drumming up a revival of interest in Germanic paganism, of all things. Because of the two composers’ longstanding personal connection, His Holiness believes that Liszt should be the one to exorcise Wagner of this perverted spirit. Franz agrees only under duress, but he sets out just the same for Wagner’s Draculean castle. (The matte painting shows it to be built in the form of a titanic head wearing a Nazi coalscuttle helmet.) There, Liszt witnesses through a hard-to-reach window a rite in which solemn, blond children in Superman costumes (except with “W” crests on the chest in place of the expected “S”) watch a bestial Jewish giant rape a bunch of nude Aryan maidens before stealing the glowing, golden glans from atop the phallic obelisk which the girls had all been worshipping previously. Then Wagner himself comes out to sing an anti-Semitic sermon, after which Cosima marches the Wagner Jugend back to the nursery. Liszt catches Wagner’s attention a moment later, and is invited in despite the irregular circumstances of his arrival. Wagner even shows off to his father-in-law the fruits of his latest great labor, a synthetic Teutonic superhuman whom he dubs Siegfried (Rick Wakeman, costumed and made up to look like a chintzy zombie version of Jack Kirby’s Mighty Thor). This is to be a momentous evening, for Wagner is about to use his music to bring Siegfried to life, launching in earnest his campaign to unify the German people by extirpating Jewish influences from their culture. Understanding at last what he has been called upon to put down, Liszt commences his exorcism— but some demons take more than a little holy water to send back to Hell permanently.

Most of the time, understanding where a movie is coming from will cause even the starkest “What the fuck?!” effect to dissipate. That isn’t the case with Lisztomania, however. If anything, tracing the roots of Lisztomania’s madness makes it look madder still. Start with Liszt’s climactic mission to exorcise Wagner of the spirit of Asatru Nazism. That isn’t something that really happened, obviously— and in any case, Liszt makes an unlikely champion of Germanic Jewry, given his efforts to efface the contributions of Gypsies (whom he incorrectly conflated with Jews) to Hungarian musical culture. Yet the most fantastical-seeming aspect of this plot thread is the one with the strongest basis in truth: among the holy orders which Liszt took from the Franciscans was that of Exorcist, so he officially was qualified to drive Wotan out of Wagner had the issue ever come up! Ken Russell’s employment of such obscure details renders his fast-and-loose approach to the overall shape of Liszt’s life story mystifying in the extreme, because it proves that the departures from reality have to mean something (even if only to Russell himself). I know why Liszt and Countess d’Agoult set their opening-scene lovemaking to the beat of a metronome. I know why Princess Carolyne is both a succubus and an emasculator during the musical number that signifies the onset of her affair with the composer. And I know why Wagner, upon being resurrected by Cosima following his exorcism, takes the form of a cross between Adolf Hitler and Frankenstein’s monster. But I can’t figure out why Lisztomania ends with its hero descending from Heaven in a pipe-organ rocketship powered by seven muses to end World War II by bombing Wagner back to the grave. Russell simply has me completely at a loss there.

As the penultimate sentence in that paragraph ought to imply, Lisztomania is probably too self-indulgent for… well, practically everybody. It takes a special sort of weirdo to appreciate a biopic that makes no sense unless you already have a firm grounding in the facts of its subject’s life, which is not necessarily the same as the special sorts of weirdo who appreciate rock musicals based on classical music, sleazy showbiz tell-alls, or hallucinatory free-form mindfucks— and it’s hard to imagine the person who can check all those boxes while also giving two shits about Franz Liszt. The most natural audience for this movie is therefore most likely the true connoisseurs of only-in-the-70’s trainwrecks. Even that pitch is misleading, though, because it’s obvious that Russell knew full well the trestle was out when he drove Lisztomania into that ravine. Rarely have I seen a filmmaker in such total command of his worst impulses. Lisztomania is stylishly tacky, intelligently dumb, substantially frothy, and wittily inane. Its utter lunacy is the product of careful deliberation, and its crassness required the utmost sensitivity to realize. It’s what you get when a very smart person has a terrible idea, recognizes it for what it is, and then goes all out to do it anyway.

The B-Masters are going back to basics with this roundtable, reviewing movies that still have the power to make us ask the question that permanently disfigured our taste in film in the first place: “What the fuck?!” Click the banner below to read about what has my colleagues baffled and bewildered.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact