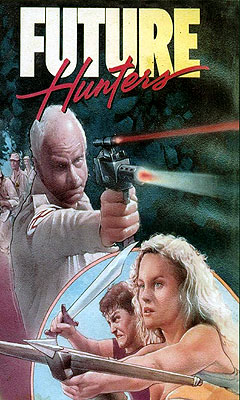

Future Hunters / Deadly Quest / Spear of Destiny / The Spear (1986) -***

Future Hunters / Deadly Quest / Spear of Destiny / The Spear (1986) -***

Depending on which of my reviews you’ve read, you might form the impression that I know a thing or two about the Filipino movie industry. That’s not really true, though. Better to say that I know a thing or to about a Filipino movie industry, for there were at least two of the things back when, and you could even make a case for three. The most accessible of the bunch for people in the English-speaking world, and the only one I’ve dealt with thus far, produced movies mainly for American consumption. The films were shot in English, they generally featured various Hollywood has-beens and bottom-feeders in the starring roles, and when they were screened at home, they did most of their domestic business in Manila, where there was a substantial American expat community until the decadent phase of the Marcos regime. The real customers were overseas, though. Oftentimes these pictures were made with American money, at the behest of American distributors, seeking to satisfy the demand from small-time exhibitors in US cities in need of ever more product to put up on their screens in the hope of luring people away from their TV sets.

That clamor didn’t begin in earnest until the 1950’s, and it ended in the 1980’s, when the proliferation of suburban chain multiplexes killed off the independent neighborhood single-screener for good. It therefore can’t account for the birth of Filipino cinema, nor can it account for its continued survival. For that we have to look to the country’s other film industry, the one that produces movies for the Philippines themselves. We will look at it one of these days, too— just as soon as I feel qualified to say something halfway intelligent about it. Alas, that day has not yet come, so suffice it to say for now that the sector of the Filipino movie industry making Tagalog-language films for domestic consumption is much older, and has proven much more durable, than its export-oriented sibling.

And that leaves us with the arguable third Filipino film industry to consider. I call it “arguable” because it’s really the successor to the one we know, and could just as plausibly be considered a continuation of it. It too made movies primarily for export, but instead of concentrating on the American grindhouse circuit, it sought to exploit the global home video market. Australia, Hong Kong, Europe, Indonesia— wherever people owned VCRs, there would now be Filipino product to play on them. Curiously, this strain of Filipino cinema has, to my taste, a distinct Italian flavor. It relies heavily on copying international blockbusters, but on miniscule fractions of those blockbusters’ budgets. The casts are frequently multinational, but don’t necessarily contain anyone you’ve ever heard of— and when there is a recognizable name, it’s usually because its owner got famous later. Story logic is simply not a consideration at all; instead, the emphasis is on cheap but gaudy set-pieces which may or may not plausibly have anything to do with each other.

The reason I bring all this up now is that there’s one filmmaker I’m aware of whose career weaves together all three of the aforementioned strands, and he’s the guy who made Future Hunters. Cirio H. Santiago is one of those directors whose work you’ve probably seen without realizing it, at least if you spent a lot of time haunting video rental shops in the 80’s and 90’s. For example, I recall once renting Stryker, one of Santiago’s numerous Road Warrior cash-ins, but mistaking it for an Italian entry in that prolific subgenre. And if you’ve got a thing for exploding bamboo, Santiago pretty much cornered the market on low-budget action movies set during the Vietnam War in the wake of Platoon.

The man goes way back. His father, Ciriaco Santiago, was the founder of Premiere Productions, one of the oldest and most important independent cinema production companies in the Philippines. Premiere began making movies for the home market in the early 1930’s, and when Cirio joined the family business 20 years later, that was what he made, as well. At the same time, though, the younger Santiago also partnered with Eddie Romero in the latter’s first attempt to create Filipino films that could be sold abroad. By 1970, Santiago had made such a name for himself that he was the first person Roger Corman sought out when he came to the Philippines to lay the groundwork for New World Pictures’ operations there. New World and American International kept Santiago busy throughout the ensuing decade and into the next, at which point Corman turned to him again to help get his post-New World venture, Concorde Pictures, off the ground. Santiago thus adjusted better than most to the rise of home video as the primary venue for exploitation filmmaking. He continued to be astoundingly prolific until the turn of the century, cranking out movies on seemingly impossible budgets and shooting schedules with the aid of a crew whose fanatical loyalty recalls stories you hear about soldiers under the command of famously beloved generals. Those folks stuck with Santiago literally to the end, too, for it took his death from lung cancer in 2008 to get him out from behind the camera permanently.

A few of you are no doubt becoming suspicious right about now. If the first thing I think of to praise about a director is his work ethic, there’s a good chance we’re in quantity-over-quality territory, right? Oh yeah. I’ve never seen any of Santiago’s Tagalog-language movies, to be fair, but the stuff he made in English… Well, he’s basically the epitome of everything I said about the third Filipino movie industry, and then some. And Future Hunters is in a way the ultimate Cirio Santiago film, because it’s basically every other movie he made in the 80’s at the same time. It’s the kind of picture that makes it worth your while to keep watching even if you’re not enjoying it much, because it turns into something completely different every ten or fifteen minutes.

We begin in post-apocalyptic action country, with soldiers of the tyrant warlord Zaar (David Light, from Mad Warrior and Demon of Paradise) pursuing a lone rebel freedom fighter across the inevitable irradiated Forbidden Zone. The latter’s name is Matthew (Richard Norton, of CyberTracker and The Blood of Heroes), and Zaar wants him eliminated for reasons above and beyond his insubordinate attitude and inconvenient fighting prowess. Somehow or other, Matthew has learned how to travel back to a time before the nuclear holocaust. Furthermore, he knows the whereabouts of the Spear of Longinus, the weapon with which one of the Roman soldiers standing guard over Christ’s crucifixion pig-stuck Jesus to make sure he was dead. In some way that is never remotely explained, the spear holds the power to alter the course of history and avert the end of the world— if someone like Matthew can send it back in time to just the right moment. Zaar reasonably reckons that no apocalypse means no job openings for post-apocalyptic warlords, so his opposition to the scheme is less crazy than it might seem at first glance. He and his minions corner Matthew in the ruined Catholic mission where the Spear of Longinus is enshrined, but they can’t stop him from escaping with it to the 1980’s.

Matthew reenters the timestream at an archeological site where an anthropology grad student by the name of Michelle (Linda Carol, of School Spirit and Reform School Girls) is taking photographs pursuant to her thesis, and bickering with her jamoke boyfriend, Slade (Robert Patrick, from Double Dragon and Equalizer 2000). The hero from the future arrives just in time to rescue the couple from a gang of outlaw bikers who apparently like to hang around ancient ruins, looking for girl anthropologists to rape. Matthew throws us all for a loop, however, by getting mortally wounded in the fight against the bikers. He lasts just long enough to entrust Michelle with the spear, impressing upon her a sense of the artifact’s critical importance, if not any clear idea what he expects her to do with the thing.

Michelle is resourceful enough a researcher to figure out pretty quickly what she’s got on her hands, but she’s also enough of a scientist to want her findings peer-reviewed. She and Slade seek out Professor Hightower (Paul Holmes, from Raiders of the Sun and Robo Warriors)— apparently the foremost living authority on the Spear of Longinus— but catch him out of the office. Hightower’s colleague, Professor Fielding (Ed Crick, from Jaws of Satan and Caged Heat II: Stripped of Freedom), is in, but I don’t know… He seems shady somehow. Michelle thinks so too. She declines Fielding’s offer to hold onto the spear for her until Hightower returns, and begins making plans to visit the latter professor at his worksite in China. Smart move, that. Fielding is secretly the head of an underground neo-Nazi army that aims to use the power of the Spear of Longinus to establish the Fourth Reich. His right-hand man, Conrad Bauer (Bob Schott, of Gymkata and Head of the Family), takes a goon squad around to the bar Michelle owns to strongarm her before opening time, but withdraws when the first customers of the day arrive.

Later, in Hong Kong, Michelle and Slade meet up with Liu (Bruce Le, from Infra-Man and The Clones of Bruce Lee), a friend of Professor Hightower’s. Liu’s martial arts prowess comes in handy when Bauer tries again at the couple’s hotel, then once more when a visit to the temple which Hightower was supposed to be studying turns up not the professor, but Legendary Super-Kicker Hwang Jang Lee (of Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and Drunken Master). Naturally Santiago couldn’t put both him and Bruce Le in the same movie without having them fight, but if you can think of an in-story reason for it to happen, then you’re working much harder at this than screenwriter J. Lee Thompson. (No, really! J. Lee Thompson wrote this shit!)

Meanwhile, the third time is apparently the charm for Conrad Bauer, who finally manages to capture Michelle. Her abduction incites Slade to a rampage of violence at Professor Fielding’s lair, which plays out like a cheaper and less heavily baby-oiled version of the attack on Bennett’s compound in Commando. Slade’s is less successful, too, although it does lead to him and Michelle meeting Professor Hightower at last. He’s chained in the same garage where the couple wind up, and thus do our heroes learn that all is not quite yet as lost as it might appear. What Matthew gave Michelle— and what Fielding now has in his possession— is only the head of the Spear of Longinus. There’s a shaft as well, without which the artifact is powerless. So far as Hightower knows, the shaft is currently lost somewhere in the jungles of Mindanao, so Fielding has a lot of work ahead of him before he can become the Fuehrer of the 1990’s. (Just don’t ask me how a wooden stick is supposed to have survived for untold hundreds of years in so soggy an environment.) Thanks to poor deathtrap design, Michelle and Slade are able to pursue Fielding and his men to the Philippines in one of the Nazis’ own helicopters, and from there on out, Future Hunters is mostly a composite ripoff of the first two Indiana Jones movies. It digresses like fucking Herodotus, though, so don’t expect it to settle into a predictable groove even now. You see, the jungle where the shaft lies hidden is home to a displaced Mongol horde, a tribe of cave-midgets who act remarkably like Ewoks, and a society of Amazon warriors led by Ursula Marquez (of Naked Doll). The latter have actual custody of the shaft, and they’re not handing it over to any man. Any woman who wants it, meanwhile, will have to face the Amazons’ fiercest fighter (Elizabeth Oropesa, from Caged Fury and The Killing of Satan) in ritualized single combat.

Shall we attempt to tally all the movies from which Future Hunters pilfers conspicuously on its circuitous route from the irradiated wastelands of the year 2025 to a girls-only Lost World in the Philippine rainforest? There’s The Road Warrior, of course, but Matthew’s mission to go back in time to prevent a nuclear war has The Terminator written all over it, too. As I’ve already mentioned, the race for control of a reputedly powerful religious artifact between Nazis and an adventurous academic plainly recalls Raiders of the Lost Ark, while several of the set pieces in the jungle are lifted whole from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Then there are the scene-specific cribs from Commando and Return of the Jedi. That’s six so far, right? Next, we have to consider all the times when Future Hunters stops short of copying any particular film, but draws on some established genre tradition not obviously related to anything else it’s doing. It’s a kung fu flick for exactly as long as Hong Kong is the setting, and a Lost World picture at the climax, and a Hitchcockian “unremarkable nobodies blunder into a nefarious conspiracy” thriller for much of its length. And of course there are those Mongols, rampaging through the story for no apparent reason, in a place where Mongols have no imaginable business being. So you see what I mean, don’t you, about just sitting back and waiting for Future Hunters’ next self-reinvention whenever it starts to lose your interest? This movie will do something you want to see sooner or later. It’s merely a question of when.

Mind you, that’s also a polite way of saying that Future Hunters is distractible to the point of utter incoherency, and that it’s totally incapable of sticking with any one thing long enough to reach a satisfying or even comprehensible conclusion. The flipside of never having to fear becoming trapped in a subplot you don’t like is that it behooves you not to invest too heavily in any subplot that you do enjoy. Woe betide, for example, the person who comes to Future Hunters for the deserts-and-dune-buggies sci-fi action flick promised by the first reel. By the time the credits roll, anyone could be forgiven for assuming that Santiago had forgotten all about the oppressed people of 2025.

Future Hunters does have one rather surprising virtue, though. As he so often would in his subsequent Vietnam movies, Santiago squeezed an incredible amount of production value out of almost no money. Most noticeably, there are a bunch of mass combat scenes in Future Hunters with actual mass to them, from the pursuit of Matthew through the Forbidden Zone through Slade’s raid on Villa Fourth Reich to the several pitched battles that Fielding’s Nazis engage in during the trek through the jungle. The secret, here as elsewhere, is the Filipino government’s rather astonishing willingness to rent out active military assets to film productions. So far as I can tell, it was the Ferdinand Marcos regime that first adopted this mercantile attitude toward the army— which makes a fair amount of sense, honestly. Marcos was nothing if not an innovative kleptocrat, and having his soldiers impersonate fictional armies on celluloid was certainly a safer way to make money off of them than hiring them out as mercenaries. Even so, the lengths to which the Filipino military would go to accommodate a filmmaker in this era were pretty astonishing. My favorite such anecdote concerns Apocalypse Now, for which a trio of hired helicopter gunships swung by to mime shooting at Francis Ford Coppola’s pretend Communist guerillas in between missions to strafe the real thing with live ammo. But to return to Future Hunters, Cirio Santiago once more exploited this unusual resource to the fullest. He might not have been able to outfit Hwang Jang Lee with a wig that would fool Mr. Magoo, but he could equip Zaar with a goddamned tank battalion! I don’t know about you, but I can’t help but be a little impressed by that.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact