Gymkata (1985) -**½

Gymkata (1985) -**½

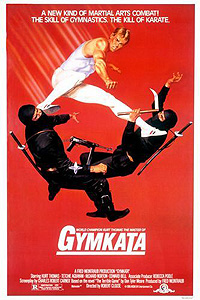

I’m mostly impervious to the charms of the American action movie in its pure form. Shootouts, explosions, and police chases by themselves generally bore me, and hand-to-hand fights need a lot more artistry than most Western action choreographers have at their disposal in order to capture my attention. Consequently, only the exceptionally great and the exceptionally lousy hold any real interest for me— and those with the sort of knowledge of Japanese that comes from watching a lot that nation’s cheap genre movies will be able to guess from the title alone into which category Gymkata falls. The word kata (well, one of the words kata— the Japanese loooovvvve their homonyms) means “method” or “technique,” including the sense applicable to the martial arts. “Gym,” meanwhile, will be familiar to anybody who ever went to an American public elementary school. That’s right— Gymkata is a white-boy chopsocky flick focused on a made-up martial art combining karate with competitive gymnastics!

You’re to be forgiven if your first question upon reading that is, “Why?” What it all comes down to is that the 70’s and 80’s were a fine time to be a washed-up athlete who wasn’t quite ready to relinquish the limelight. Bodybuilders, kickboxers, football players, wrestlers, and even the occasional basketball star were enjoying profitable second careers as big-screen action heroes (or at least big-screen bad-guy henchmen), so why not a gymnast, too? That line of reasoning must have seemed especially compelling to Kurt Thomas, seeing as he got shafted out of what should have been the climax to his athletic career when the US boycotted the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow as a gesture of protest against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Of course, being a gymnast meant that Thomas was rather a little guy, so clearly he wasn’t going to be the next Arnold Schwarzenegger. The next Chuck Norris, though? Sure— why not? After all, the Asian martial arts are a lot like gymnastics insofar as they emphasize precise muscular control over simple brute strength, so the training Thomas had already undergone ought to be fairly readily applicable. Plus, if the fight choreographer could rig it so that Thomas could use some of the moves that had won him a place on the Olympic team that stayed home in a huff, the producers could sell the film as the emergence of a whole new martial art— and that’s just what they proceeded to do.

Oh— and they made the movie sort of a sideways Most Dangerous Game rip-off, too! Somewhere in what is absolutely not Yugoslavia (the Zagreb shooting locations are interesting in and of themselves, since Tito’s successors were still officially among the bad guys in 1985), a man who will later be identified to us as Colonel Cabot (Eric Lawson, from Skeeter and King Cobra) flees through the forest from a burly steppe horseman (Richard Norton, of Cybertracker and Future Hunters) and his entourage of Golan-Globus ninjas. The chase leads Cabot to a deep gorge, which has oddly been bridged by several parallel ropes, rather than by any remotely useful apparatus. Cabot grabs hold of one, and shimmies nearly to the other side of the gorge before his pursuers arrive. The lead hunter climbs down from his horse, nocks an arrow, and takes aim. Cabot has just enough time to protest that what his foe is about to do is against the rules before the arrow finds its target.

An unspecified but seemingly short while later, a US government intelligence agent named Paley (Edward Bell, of Earth II and The Premonition) accosts Cabot’s son, Olympic gymnast Jonathan Cabot (Thomas, obviously), with a rather unlikely pitch. It turns out the place where the elder Cabot met his apparent end was a little Central Asian khanate called Parmistan, which interests the Feds not because it’s full of oil or sits next-door to something the Russians don’t want us to know about, but rather because it would be the ideal site for a coordinating center managing the early-warning aspect of Ronald Reagan’s delusional Strategic Defense Initiative satellite network. The trouble with Parmistan is that you can’t just go there and enter into negotiations with the khan (Buck Kartalian, from Planet of the Apes and Please Don’t Eat My Mother, looking for all the world like a gone-to-seed Mel Brooks) the way you can in any halfway normal country. No, any outsider hoping to set foot in Parmistan must first prove their worthiness of such an honor by successfully participating in the Game— which no outsider has managed in something like 900 years. As you doubtless already realize, contestants in the Game submit to being hunted through an already very dangerous obstacle course by the khan’s vizier and a contingent of soldiers. Make it to the finish line alive, and you win not only admission into Parmistan, but also a single wish encompassing anything that it is within the khan’s power to grant. Paley is hoping that Jonathan will agree to take his father’s place in the effort to open Parmistan to American diplomacy, competing in the Game and blowing his wish to secure a lease on Parmi territory for that hoped-for SDI base. The only thing more incredible than the idea that Paley would go outside the CIA (or whatever agency he represents) to recruit an operative is the idea that Jonathan would sign on for such a thankless and plainly crack-brained scheme.

Jonathan does just that, however, and Paley whisks him off to a secret compound in the country someplace, where a pair of trainers (Sonny Barnes, of The Big Brawl and Force Five, and Tadashi Yamashita, from The Octagon and Sword of Heaven) will whip him into proper shape for the competition. Paley also introduces Jonathan to the khan’s daughter, Princess Rubali (Tetchie Agbayani). (“Interesting background,” Paley says of the princess, “Her mother was Indonesian.” Plainly there’s a story there— but don’t you go thinking you’ll ever get to hear it!) Rubali is, as the spy movie cliché has it, our man on the inside. We need one of those in Parmistan, too, because rumor has it that Vizier Zamir is working for the Russians on the side. How obsessively insular Parmistan manages to conduct this sort of Cold War back-door diplomacy when no foreigner is permitted to enter the country without winning the Game— which, I remind you, no foreigner ever has in the last nine centuries— is an excellent question. I encourage you to write me with your answer if you ever figure it out. Anyway, we get a weak-ass gwailo version of the usual fu-film training montage here (watch for Yamashita’s demonstration of his awesome one-handed two-handed hatchet-fighting technique), intercut with an equally weak-ass version of the usual romance flick falling-in-love montage pairing Jonathan with Rubali. That last part is going to become a problem for the kids later, because Parmi political tradition has it that the khan’s daughter must always marry the vizier. You’d think Rubali might have mentioned that she was engaged before submitting to Jonathan’s courtship, but apparently you’d be wrong.

His training complete, Jonathan embarks for “Karabal, on the Caspian Sea, about 100 miles from Istanbul.” Umm, no. If you’re 100 miles from Istanbul, that’s the Black Sea you’re looking at; if you’re on the Caspian, then you’re at least 1000 miles from Istanbul. Whichever sea it fronts onto, Karabal is the site of Gymkata’s first major action set-piece, for Jonathan, Rubali, and their handlers are attacked on the street at night by gunman working for a terrorist called Tamerlaine (Slobodan Dimitrijevic). Rubali is captured and the CIA bodyguards are killed, but the attack’s only effect on Jonathan is to make him determined to effect a rescue. The next morning, in defiance of orders from Mackle (Zlatko Pokupec), the local liaison for the operation, Jonathan slips into Tamerlaine’s headquarters, fights his way past all the guards, kills Tamerlaine himself, and springs Rubali. The getaway chase sets an important pattern for the film, in that Karabal turns out to be weirdly well-stocked with random architectural features that just happen to bear marked resemblance to pieces of gymnastics equipment like high bars, pommel horses, and such. If you think getting kicked in the face the old-fashioned way hurts, just imagine how it feels with a half-dozen overhead full-body swings behind it! The rescue doesn’t get Jonathan or Rubali out of trouble, however, for Mackle turns out to be a double agent— although I’m at a loss to tell you whether he’s doubling for Tamerlaine, Zamir, the Russians, or some combination of the above. Luckily, Paley pops up in the knick of time to machine-gun our heroes’ troubles away.

Next stop: Parmistan! Jonathan’s reception is not exactly what I’d call friendly (more Golan-Globus ninjas are involved), even though he’s got Rubali along to act as a living writ of safe conduct. But when Jonathan emerges from unconsciousness, he finds he’s being treated hospitably enough. Evidently, he’s officially the guest of the khan until the commencement of the Game tomorrow morning, and like the other contestants (a multitude of nations have sent their top athletes to compete, although no reason for this is ever elucidated), he is among the guests of honor at a big royal festival on the night before the event. Jonathan also gets a preview of the Game itself, for he is strangely allowed to accompany Zamir and his huntsmen as an observer when a trio of criminals have their death sentences commuted to a run through the course. It is here that we learn of the rule forbidding the hunters to attack their prey while traversing one of the major obstacles, unless the hunters place themselves in the same position at the time— in other words, no shooting arrows at contestants climbing ropes, unless you’re hanging from a rope of your own. Huntsmen who break the rules forfeit their lives, just like regular contestants. We also learn (this time from Rubali) that Parmistan is currently torn by political strife, with the khan facing conflicting demands from traditionalists pandered to and exploited by Zamir (and therefore presumably favored by those dirty, rotten, stinking Reds) and reformers known as the Twenties because of their desire to see Parmistan enter the 20th century. Rubali, as you might guess, inclines toward the Twenties’ position, although she has not formally declared herself for one side or the other.

But enough of this plot bullshit; let’s talk about the Game. First, the players must make a five-mile run through the swamps outside of the khan’s capital, until they reach a 200-foot cliff. That cliff forms the first transitional obstacle, which the contestants must scale by means of a set of ropes affixed to its head. Then comes another prolonged run across the plateau, terminating in that gorge we’ve already seen. Another straightaway comes after that, followed by a swim downstream in a fast-moving river and a hike up a steep, wooded hill. Atop the hill is the most challenging obstacle of all— the Village of the Damned, where all the insane people in Parmistan are sequestered untreated and unsupervised. In the hugely unlikely event that anyone finds his way through the Village of the Damned alive, the final leg of the course will carry them back across the swamp to the capital. Officials are positioned all along the route to make sure that nobody gets turned around, and supposedly to keep Zamir and his Golan-Globus ninjas honest in their pursuit as well. If there’s one thing 80’s action movies have taught us, though, it’s that no force on Earth can keep someone honest when they’re working for the Ruskies. Furthermore, when we get a look at those officials, it turns out they’re just more Golan-Globus ninjas. Yeah, the people running this race are so fucked. Also, there’s one contestant this time around who is determined to make sure not merely that he wins, but that he’s the only one who does. And since Thorg (Bob Schott, of The Working Girls and The Norliss Tapes) is even huger than Zamir, Jonathan and the other runners probably ought to be worrying at least as much about him as they are about anything else.

Despite the fact that I keep referring to Zamir’s minions as Golan-Globus ninjas, the truly astonishing fact about Gymkata is that Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus had absolutely nothing to do with making this movie. Gymkata was an MGM release, hard as that is to believe, although there was indeed one major bad-action luminary involved behind the scenes. Perhaps you remember him— a man by the name of Robert Clouse? This was Clouse’s last film of the 1980’s, and it isn’t hard to guess why. Black Belt Jones looks positively respectable alongside Gymkata. The action choreography is fairly solid, so long as you can turn a blind eye to the increasingly glaring contrivances necessary to enable Kurt Thomas to incorporate some of his championship-winning moves into a fight scene. Otherwise, though, we’re looking at a pretty steady litany of failure, with limp acting, a ridiculous story that becomes more ridiculous with each moment you spend thinking about it, and a bottomless, sucking vacuum of anti-charisma at its core. One thing I can promise you is that you will not go away from Gymkata wondering why it didn’t launch Kurt Thomas on a movie career at least as successful as Jim Kelly’s. The poor sap has all the screen presence of reheated oatmeal, leaving him nothing to fall back on when he reaches the limits of his acting ability— which tends to happen the instant anyone turns on the camera. Even Bob Schott leaves more of an impression, and he’s got nothing going for him beyond a distracting and contextually hilarious resemblance to a roided-out Scott Thompson! The one sequence in which Gymkata ever comes close to working the way its creators wanted is during Jonathan’s transit of the Village of the Damned. Some deeply weird shit goes on during that segment of the film (there’s a guy with faces on both sides of his head, for fuck’s sake!), and for about ten minutes, it’s like we’re watching a completely different and much better movie. A fellow B-Fest attendee hit the nail on the head when he called it “the Silent Hill part,” but unlike that much more recent film, Gymkata never offers any explanation for its little town of nightmares beyond that it’s where all the crazy people live. The Village of the Damned just sits there, defying you to make any sense of it, until its function in the plot has been served, and then it’s never mentioned again. It’s a striking example of the “panning for gold” aspect of bad movie fandom, one of those brief flashes of cockeyed brilliance that occasionally reward us for putting up with so much utter crap.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact