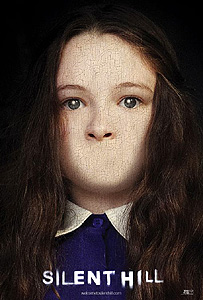

Silent Hill (2006) **½

Silent Hill (2006) **½

Considering all the remakes of Japanese and Korean horror movies to have emerged from Hollywood in the years since The Ring, I find it a little surprising that J-horror sensibilities haven’t had more impact on Western filmmaking otherwise. For all the past decade’s compulsive duplication of notable Asian fright films, and for all the success that must have greeted those movies to judge from the sheer number that got made, Hollywood has exhibited strangely little interest in native-born stringy-haired ghost girls or out-of-the-way American towns cursed with outbreaks of utter irrationality. Silent Hill might count as a sort of half-measure in that direction. It has both a cursed town and a stringy-haired ghost girl, but it isn’t a remake of a movie released in East Asia three years earlier. It is, however, of Japanese extraction in the sense that it derives from the video game series of the same title, launched by Konami in 1999. Perhaps it’s inevitable, given that mixed parentage, that Silent Hill would represent a somewhat shaky compromise between Asian and Western styles of horror-movie storytelling, positing a scenario to which no explanation could really do justice, and then insisting upon explaining it anyway.

Nine-year-old Sharon DaSilva (Jodelle Ferland, from They and Bloodrayne II: Deliverance) sleepwalks. Sometimes these episodes even carry her outside the house where she lives with her adoptive parents, Rose (Radha Mitchell, of Pitch Black and Rogue) and Christopher (Sean Bean, from The Island and The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring), and since the DaSilva place is within comfortable hiking distance of what looks like a quarry-turned-reservoir, that’s an even more frightening prospect than it would have been anyway. What’s more, it would appear that Sharon’s somnambulism is tied to a recurring dream, as she invariably says something about “home” and “silent hill” during her trances. Christopher seems to believe there’s a pharmacological solution to Sharon’s problem, but Rose has grown increasingly convinced that this “silent hill” is a real place, and that it figures in some troubling buried memory from Sharon’s earliest infancy. A bit of hunting on the internet turns up the existence of a town by the name of Silent Hill in West Virginia, together with the curious fact that the place has stood abandoned for more than 30 years. Silent Hill was a coal-mining town, and the coal vein it sits atop caught fire in 1974; the fires under the ground have been burning ever since, and the town is now uninhabitable due to the toxic fumes that seep continually up from the blazing mine. The adoption agency from which Rose and Christopher acquired Sharon did report that the girl had been born in West Virginia, although no one said anything about Silent Hill specifically. Rose hopes that if she takes her daughter to see the empty town, her repressed memories will come to the surface, and put a stop to her dangerous nocturnal wanderings. It’s a defensible plan, but the way she carries it out— tossing Sharon in the car one morning after Christopher has left for work, and driving relentlessly south without so much as a scribbled note on the dining room table to explain their absence— might charitably be described as deeply stupid.

In addition to all the obvious things that are wrong with Rose’s psychotherapeutic strategy for her daughter, there’s the very slight problem that Silent Hill does not appear on any map that she can find (which is rather odd, since we’ll see later that it still has a highway turn-off sign, and that the road leading there is closed only in the sense of having a flimsy wire-mesh gate erected across it). All Rose has to go on is what she was able to extract from the internet, which is that Silent Hill is somewhere near Brahams, the Toluca County seat. Also, she left her laptop turned on when she pulled her vanishing act this morning, and the browser log is full of websites about ghost towns. Christopher figures out what Rose has done not long after returning home, and he immediately goes about erecting whatever obstacles are within his power to slow her down— like putting a freeze on their credit and ATM cards to limit the amount of gas she’ll be able to buy, for example. For a while, it even looks as though Christopher might have dropped a line to the police in Toluca County, because Rose and Sharon attract a rather unusual amount of attention from Officer Cybill Bennett (Laurie Holden, of TekWar: TekLab and The Mist) when the three of them wind up at the same rest stop. In truth, though, Bennett just has a special hate-on for kidnappers, and her suspicions are aroused when Sharon freaks out over something just after her mom finishes filling up the gas tank. What has Sharon so bent out of shape is the set of disturbing crayon drawings that she apparently made while asleep in the back seat, but Bennett is too far away to catch any of the details, and I kind of doubt that she’d grasp the true significance of the incident anyway. In any case, Bennett notes down Rose’s license plate number, and follows her at a discreet distance all the way to the Silent Hill turn-off— at which point she pulls Rose over on who knows what pretext. Rose, recognizing that she’s about to be fucked with, stops her car, but then floors the accelerator as soon as Bennett is fully dismounted from her motorcycle. Winding mountain roads aren’t the safest venue for a high-speed chase, however, and both Rose and Bennett lose control of their vehicles just a few hundred yards past the gate meant to seal off Silent Hill. Here’s the weird thing, though: we don’t get to see what makes Bennett ditch her bike, but Rose skids into a rock face while trying to dodge a little girl in a purple dress (also Jodelle Ferman, although it’s too dark for that to be really apparent just yet), who stepped out into the road seemingly from nowhere. Bennett and Rose alike crack their heads on something in their respective crashes, and both remain unconscious until well after dawn.

When Rose comes to, the mountains are shrouded in a dense fog, and flakes of ash are drifting down from the sky like a gentle snowfall. Sharon is not in the Jeep. Close to panic now, Rose runs all the way into downtown Silent Hill, calling out all the while for help— for all the good that’s going to do her in a ghost town. Eventually, she begins catching glimpses of that other child, and it’s while Rose is pursuing her that Silent Hill first shows its true, horrid colors. Without warning, what sounds like an air-raid siren starts to blare, and the sky goes suddenly dark as midnight. When Rose emerges from the alley she’d been traversing at the time, she finds herself in a maze of wire-mesh fencing, where she is beset by a mob of creatures that resemble oversized, deformed babies with bodies made of smoldering ash. The ash-children herd her through the maze until she seeks escape by ducking into what turns out to be the rear entrance to a bowling alley. They force their way inside after her, but Rose gets unaccountably lucky. The light returns as suddenly as it vanished, and the creatures all disintegrate into nearly weightless ash-flakes; the maze, meanwhile, transforms into a succession of ordinary fenced-in backyards.

That experience naturally contributes a new urgency to Rose’s search for her daughter, an urgency which is redoubled when she discovers that she’s not alone in Silent Hill after all. For one thing, Cybill Bennett has followed her, now totally convinced that Rose abducted Sharon, and intent on bringing her to justice. There’s also a madwoman named Dahlia Gillespie (Deborah Kara Unger, from Highlander: The Final Dimension and Crash) who is on the hunt for a missing daughter, too— one who looks exactly like Sharon, if we’re to judge by Dahlia’s reaction to seeing the cameo that Rose carries in her locket. Then there are the men in miner’s suits who patrol the town in small bands, armed with improvised clubs; there’s no telling yet what their deal is, but Rose is surely wise to assume that they’re dangerous to her and Sharon both. And of course there are the monsters that come out at more or less regular intervals, every time the sky goes black and the siren sounds. The ash-kids Rose contended with earlier are far and away the most benign of that lot, too. On the upside, somebody, be it Sharon or her double, keeps leaving obviously deliberate clues for Rose to follow, hinting at discoveries to be made in virtually every institutional building in Silent Hill: Midwich Elementary School, the Grand Hotel, a decidedly pagan-looking church, the municipal hospital. But on a downside even downer than the periodically recurring Mad Monster Parties, all the roads leading into and out of Silent Hill now terminate in seemingly bottomless rifts in the earth, as if the whole town had been magically wrenched free of its mountainous perch, and left to hang in an infinite void of impenetrable mist. That’s going to be a hell of a lot tougher to get around than the sorry little gate the highway administration set up by way of a roadblock, although seeing the boundless chasm does at last convince Officer Bennett that she has more pressing concerns than arresting Rose.

While Rose is contending with all that, Christopher is doing his best to follow her trail. Eventually, he reaches the Silent Hill turn-off, where he meets Inspector Thomas Gucci (Kim Coates, of Skinwalkers and Waterworld). Gucci is on the same police force as Cybill Bennett, and he and his men have spent the whole morning trying to figure out what to make of Bennett’s abandoned motorcycle, a similarly abandoned Jeep Liberty with Ohio tags, and a hole rammed through the gate blocking access to a town where no one’s had cause to set foot in three decades. Naturally, that makes him at least a little bit happy to see Christopher. The detective’s foray into town with Christopher in tow gets us one step closer to understanding what’s going on in Silent Hill, for the place shows them no sign of anything weirder than the effects of 30 years of unchecked entropy. No fog, no drizzling ash, no roving gangs of miners, and certainly no swarms of flesh-eating insects or burly, seven-and-a-half-foot men with butcher’s aprons, wedge-shaped cast-iron helmets, and swords the size of logging saws. And that’s true even though the men are in Silent Hill at the exact same time as Rose is fleeing through Midwich Elementary from the reanimated corpse of a janitor, which had been trussed up with barbed wire in a bathroom stall, in a manner that might have impressed even the Cenobites. Evidently, the whole town of Silent Hill is what Poltergeist’s Dr. Lesh would have called an area of bilocation, existing simultaneously on two planes of reality. Christopher begins to get an inkling that something unnaturally weird is going on when he and Rose pass each other on the same street in their respective dimensions, and Chris realizes that he can smell his wife’s perfume. That inkling grows stronger, too, when Gucci stonewalls his questions about the history of Silent Hill, and begins making obvious efforts to get him swiftly away from the town. A subsequent call to the Toluca County Archives in Brahams reveals that the records for Silent Hill are all sealed, but Christopher is not above a little after-hours breaking and entering at this point. His snooping in the archives uncovers a file with Gucci’s name on it, recounting how a little girl was burned nearly to death under very peculiar circumstances just a few weeks prior to the mines catching fire in 1974. The girl’s name was Alessa Gillespie, and there’s a photo of her at age nine in the file. It would appear that we now know the name of Sharon’s mysterious double.

Back in Silent Hill, and back on the Other Side, Rose and Cybill have declared a truce, and are putting some of the pieces together themselves. At the Grand Hotel, they meet a woman named Anna (Tanya Allen), who leads them to the church the next time that inexplicable, hellish darkness falls. It turns out there are dozens if not hundreds of people trapped in this weird pocket-dimension, all of them members of a witch-obsessed cult led by a preacher-prophetess called Christabella (Alice Krige, from Reign of Fire and Habitat). The cultists claim descent from Silent Hill’s founders, who were none too fond of the Black Arts themselves, if the huge mural of a woman being burned at the stake behind the altar of the church is any indication. It is their belief that the ghastly things that happen in Silent Hill during its periods of darkness are the work of a powerful demon who dwells in the basement of the old hospital, and that they are the only survivors of an apocalypse unleashed upon the world by that demon. They also take an intense dislike to Dahlia Gillespie, and observe a taboo against speaking Alessa Gillespie’s name. Do you figure that might mean they considered Alessa a witch? And given what traditionally becomes of witches, do you think that might fill in some of the back-story to that police file Christopher found at the County Archives? Finally, do you think there might be some connection between the little girl who was burned to a crisp 30 years ago and the menagerie of monsters who’ve been preying on those trapped in the Limbo version of Silent Hill ever since?

The main trouble with Silent Hill is that it eventually offers clear and detailed, but also fairly ridiculous, answers to those questions and a slew of others, so that it simultaneously makes both a little too much sense and not nearly enough. So long as we have only the vaguest clue what’s going on in the extradimensional town, Silent Hill is gripping, unnerving, and occasionally honestly scary. The film tips its hand early on to being a variation on the portal-to-hell premise (in fact, viewers who’ve seen Carnival of Souls will catch on the instant Rose awakens in the driver’s seat of her crashed car), which gives writer Roger Avary and director Christophe Gans license to violate every rule of normal logic they can think of. And violate they do, with admirably disorienting effect. It’s a rare case in which there’s a defensible reason for constructing a movie according to the assumptions of video game storytelling, because in Silent Hill, there really is an unseen intelligence meddling constantly with the rules governing reality in order to aid some people and make life difficult for others. Silent Hill also boasts some of the most disturbing monster designs to appear in a widely released movie since Hellraiser (indeed, none of them except maybe the bugs would seem out of place in the universe of that film and its sequels), and although all but two were carried over more or less directly from one or another of the Silent Hill games, the present filmmakers nevertheless deserve credit for both their fidelity to the inherited bestiary and their decision to make the maximum workable use of practical effects in translating the creatures to the big screen. Freaky though the giant with the big, pyramidal helmet is as an arrangement of polygons, he’s infinitely more so as a living actor. For about an hour and a half, Silent Hill is like some ghastly fever dream, which is exactly what it ought to be.

Unfortunately, at the end of that hour and a half, Rose makes contact with the entity that created and basically runs the pocket-universe version of Silent Hill, and *KABOOM!!!!*— Avary and Gans set off a 20-megaton exposition bomb, and come perilously close to blowing the whole movie to hell. Seriously, it’s almost as bad as the conga line of explanatory lectures and flashbacks that makes up the last third of In the Folds of the Flesh, and the only positive things I can think of to say about it are that Ganz and Avary have the good sense to limit the voiceover narration that accompanies the flashbacks to a scene-setting line or two at the onset of each segment, and that they subsequently put the presumed villain’s interminable dissertation to good use by having it redefine the terms of the conflict going into the endgame. Mitigating circumstances or no, however, the effect on Silent Hill’s momentum is roughly the same as that of Lucy yanking the football away from Charlie Brown as he runs in for a kick. This sequence also wreaks havoc on the story in the sense that it offers pat, cliched, and ill-considered explanations for many of Silent Hill’s supernatural manifestations, which diminish their effectiveness, yet simultaneously seem nowhere near adequate to account for them. Let’s start with the fate of Alessa Gillespie, the event from which everything else ultimately stems. Tell the truth, now— doesn’t it seem to you that 1974 is just a little late for a witch-burning, even in West Virginia? Meanwhile, can you really see a little girl dreaming up any of the creatures that roam Silent Hill during its periods of darkness, except for maybe the ash-babies? It’s not that the monsters are too gruesome (children can be a lot more twisted than grown-ups like to imagine), but rather that they’re too adult and too masculine in the specific forms of horror that they conjure up. Please— a pack of scalpel-wielding Naughty Nurses with nothing but huge, seeping wounds where their faces ought to be? That’s the nightmare vision of a sexually frustrated man, not a nine-year-old girl whose principal tried to barbecue her to death for supposed transgressions she wasn’t yet mature enough to understand! And good luck assembling the data into a comprehensible whole when the Official Silent Hill Spokesspirit finally reveals how whatever’s left of Alessa is doing these days. Going into detail would give away more than I want to, but suffice it to say that the girl has more avatars than a Hindu deity, with not a clue in sight as to how she came by them all. Perhaps you think it unfair of me to criticize Silent Hill for resolving too many of its mysteries with one breath, and for leaving others hanging with the next, but I disagree. It’s a matter of picking the right questions to answer, and then answering them in a satisfying, intelligible manner. Silent Hill answers too many of the wrong questions, and its answers too often make nonsense of what coherency the film had contained from the outset.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact