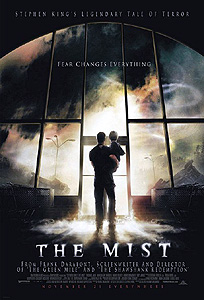

The Mist (2007) ****

The Mist (2007) ****

Well, would you look at that… And here I thought the creation of non-sucking Stephen King movies was a lost art! You must agree that it boded ill for the future when the TV and direct-to-video markets pushed the fat part of the King-movie bell curve so far to the left that even Maximum Overdrive wound up within spitting distance of the right tail. Frank Darabont, meanwhile, is in no sense the person I’d have picked to spearhead a King renaissance. His first try at adapting King’s writing, The Shawshank Redemption, was indeed very good, but it was hardly what most people imagine when they hear, “Based on the novel by Stephen King.” Darabont’s second go-round, The Green Mile, was a little closer to the mark in the sense that it at least included an element of the supernatural, but it was still fundamentally an off-kilter prison drama that fairly reeked of desperation to be taken seriously by people who would have no respect for the likes of Creepshow or The Dead Zone. Also, the book it was based on was so resolutely craptacular that a film version on par with Children of the Corn would have been an improvement. And yet here Darabont is with The Mist, the first top-notch Stephen King movie since maybe the early 80’s, adapted from one of the last top-notch tales by that author to escape the film industry’s attention.

David Drayton (Thomas Jane, from Deep Blue Sea and Buffy the Vampire Slayer) is an illustrator specializing in movie posters. One evening, the little Maine town where he lives with his wife, Stef (Stormswept’s Kelly Collins), and son, Billy (The Hole’s Nathan Gamble), is wracked by an incredible thunderstorm, and a scene of immense havoc greets the Draytons when they emerge from hiding in the cellar the next morning. Power and phone lines are down, of course, and the yard is strewn with all manner of debris. The storm also knocked down a tree that had stood since David’s grandfather owned the house, and Granddad’s tree took out the addition that David uses (excuse me— used) as his painting studio in its fall. There’s another big tree down, too, and it smashed the Draytons’ boathouse even more thoroughly. As if that weren’t bad enough, the boathouse-killing tree belonged not to the Draytons, but to their next-door neighbor, Brent Norton (Andre Braugher, of Frequency and the 21st-century ‘Salem’s Lot), with whom they’ve had serious trouble in the past. You know the saying about how people see the world when their only tool is a hammer? Well, Norton’s a lawyer, and I bet you can all guess what his only tool is. Stef worries that things could turn ugly when David heads next door to trade insurance information with Brent, but the destruction of the lawyer’s vintage Mercedes (assuming a 1980 can credibly be considered “vintage”) by yet a third fallen tree has left him in a curiously philosophical and approachable mood. Brent and David don’t exactly kiss and make up, but it’s obvious that some manner of truce has been declared when Norton not only doesn’t raise a fuss over his errant tree, but asks Drayton to drive him into town for a grocery and hardware run. David tells Stef that he’ll be back shortly with some plastic sheeting with which to seal up the shattered addition, and then drives off with both Billy and Brent.

With all the other demands on everybody’s attention, it would be very easy to overlook or disregard the dense fogbank rolling slowly toward town from across the lake. Sure, it doesn’t seem to be behaving like any comparable meteorological phenomenon should around these parts, but who cares about weather that’s merely screwy when you’re just beginning to clean up after the ruinous weather of the night before? Also, there’s another conspicuous claim on people’s attention, in the form of the steady stream of military vehicles that have been convoying toward the Army base on the far side of the lake all morning. It would be one thing if all those troops had been called out to contain a flood or to help maintain order while the police and fire department dealt with the various emergencies caused by last night’s storm, but the only soldiers coming into the village itself have been MPs detached to round up and recall men on leave from the base like Private Wayne Jessup (Sam Witwer) and the two companions with whom he was hoping to get away to the nearest city. Brent asks David if he has any idea what’s behind all the military activity, but all Drayton can tell him is that the base is supposed to be home to something called the Arrowhead Project— whatever the hell that means. Yet another more pressing concern than funny fogbanks over the lake comes to light when David, Brent, and Billy step inside the Food House grocery store; their shopping trip is going to be a more involved and time-consuming undertaking than anticipated. It’s bad enough that half the town seems to be there— everybody from Jessup and his buddies to Billy’s teacher, Irene Reppler (Frances Sternhagen, from Outland and Misery), to Mrs. Carmody (The Invisible’s Marcia Gay Harden, looking remarkably like a counterfeit Karen Black) the local religious loony. (No little town in the Stephen King universe can be without one of those, after all.) With no phone service or electricity, there are also no card readers or cash registers, so Sally (The Chronicles of Riddick’s Alexa Davalos) and the other cashiers have to ring everybody up the old-fashioned way. The checkout lines are horrifying.

Still, that mist really is the thing people ought to be worrying about. As the fogbank advances toward the Food House, an old man named Dan Miller (Jeffrey DeMunn, of Citizen X and The Blob) races into the store hollering his head off, with an alarming quantity of blood spattered all over his face and torso. Miller eventually settles down enough to communicate that he and a friend had been caught in the oncoming mist, and that something within and concealed by it seized the other man and did something unbelievably destructive to him. Obviously, this tale is a little short on credibility, but all that blood sure as hell came from somewhere. That’s when the siren at the firehouse goes off, and squadron of police cars tear ass up the street into the fog, their own sirens blaring. Then, as the mist envelopes the parking lot, a piercing scream from outside lends further unwanted support to Miller’s story. Drayton gets even more when assistant manager Ollie Weeks (Toby Jones, the voice of Dobby the house elf in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets) allows him into the back warehouse to search for something like a blanket to wrap around Billy, who is by this point approaching hysterics from the sudden outbreak of weirdness. While performing this errand, David has the impression of something huge pressing against the roll-up door to the rear loading dock. But the final confirmation comes only when three Food House employees attempt to clear an obstruction from the exhaust vent for the diesel emergency generator. Stockers Jim (William Sadler, from Disturbing Behavior and The Green Mile) and Myron (David Jensen, of The Reaping and The Skeleton Key) open up the loading dock so that Norm the bag boy (Chris Owen) can climb up to the outside vent, and a bunch of freaky purple tentacles come slithering in! Norm is dragged to his death before Drayton can motivate the panic-paralyzed stockers into closing the goddamned door. Even then, David has to chop off part of the biggest tentacle with an axe in order to get the loading dock secured.

It’s a good thing that piece of tentacle remained inside, too, because not one person among the Food House shoppers would believe David, Myron, and Jim’s account without it to offer up as proof. Well, maybe Mrs. Carmody would believe it, since giant, bag-boy-eating tentacle monsters would seem to dovetail nicely with her preferred explanation of the mist— that the opening act of the apocalypse is underway, and the angel with the seven sealed vials has already popped open two or three of them. Brent Norton calls bullshit even when presented with the severed monster-limb, imagining instead some elaborate townie conspiracy to make a fool of the slick, big-city lawyer. Thus do factions begin to form among the crowd fogged in at the Food House, for Carmody and Norton are persistently voluble in preaching the competing gospels of God’s world-ending wrath on the one hand, and weird and potentially dangerous, but perfectly natural weather phenomena on the other. Brent attracts more adherents at first. However, they remove themselves from the equation early on by setting off into the mist to summon help. Furthermore, the grisly fate of the last man among them to leave the store (Brian Lioby, from Dreamscape and Chiller) has the effect of making Mrs. Carmody’s version of events sound a little more convincing. Something horrendously out of the ordinary is clearly going on when bikers get torn in half by barely-glimpsed monstrosities, and in the relatively unsophisticated and fundamentally Christian worldview characteristic of small-town America, Armageddon sounds like as good a name as any to hang on such a terrible upending of ordinary reality. With each new horror that manifests itself— the venomous, palm-sized, mosquito-like insects that swarm the store after sunset; the pterosaur-things that follow to feast on the deadly bugs; the disturbingly mammalian spiders that infest the pharmacy next-door to the Food House— Mrs. Carmody’s following becomes larger and surer of their leader. When the self-proclaimed prophetess starts harping on the need for expiation by blood sacrifice, Drayton, Weeks, Mrs. Reppler, a new third-grade teacher at Billy’s school (Laurie Holden, of Silent Hill and TekWar: TekLab), and a few others who haven’t yet succumbed to the allure of a convenient, pat answer begin to wonder if maybe they wouldn’t be safer out there with the monsters.

It’s next to impossible to read a discussion of The Mist— either the movie or the novella— without encountering the word “Lovecraftian,” and that pattern is going to hold true here as well. However, simply to invoke H. P. Lovecraft’s name says less about The Mist than appears to be recognized by most of the people who’ve been doing it, for there are really two parallel strains in Lovecraft’s fiction, and The Mist is most closely akin to the less well-publicized of them. H. P. Lovecraft, as is well known, dealt mainly, even obsessively, with the theme of horrible secrets beyond the ken of sane humanity, and in his most famous tales, that usually means some hidden supernatural evil of vast power and even vaster antiquity. But Lovecraft also devoted more than a little of his time to stories about dreadful and unsuspected natural phenomena. There’s nothing either numinous or demonic about the clan of degenerate aristocrats in “The Lurking Fear”— they just kept on fucking their siblings generation after generation until all of their chromosomes broke. There’s nothing unnatural about the hyper-intelligent sea cucumbers from outer space in At the Mountains of Madness— they’re just not from around here. Likewise, what we see in The Mist is not an outbreak of supernatural evil, but the intrusion of an alien form of nature into our own. The ingenious thing about King’s story, which Darabont wisely retained in the film version, is that the things in the mist are not merely a menagerie of monsters. They’re an ecosystem, and the behavior of each species is readily comprehensible in terms of basic biological drives. Consequently, the movie’s supreme moment of irony may not be the extremely divisive ending (about which we’ll talk in a bit), but rather the confrontation between Mrs. Carmody and the otherworldly bug. Several of the insects from the mist gain entry to the Food House on the first night, and one of them stings Sally the cashier to death. Meanwhile, a second bug buzzes over to Mrs. Carmody, but rather than freaking out the way Sally did, she stands serenely in prayer, declaring her acceptance of whatever fate God has set aside for her. When the insect does not sting her, but goes on about its business, she takes it as a sign from on high, and later uses the incident as a credential of sorts while preaching the necessity of human sacrifice to her burgeoning cult. But anyone who has ever observed the behavior of bees or wasps knows that nearly all species of stinging insect will lose interest in you if you ignore them, provided you aren’t within the defensive perimeter of their nest. In other words, what is really the surest indication that the mist-things are just very strange animals, and can be understood and dealt with accordingly, gets twisted by Carmody and her followers into its diametric opposite. Fear of the unknown has taken away their wits so thoroughly as to affect even the sort of basic common sense that simple, small-town people such as these are conventionally supposed to possess in abundance.

The Mist was promoted with the tag-line, “Fear changes everything,” and it is indeed about fear in a way that very few horror movies I’ve seen are. Virtually every action taken or decision made by any of the characters is an occasion for examining how they manage and mismanage their fear. Fear makes unlikely heroes out of Ollie Weeks and Irene Reppler; it makes cowards out Wayne Jessup’s friends from the Army base (who, we come to suspect, were so hot to spend their leave time out of town because they knew something about what had gone wrong with the Arrowhead Project); it turns the logic-trained Brent Norton into a willfully unreasoning fool, and the staunchly Christian Mrs. Carmody into a bloodthirsty pagan priestess. Cheerfully proper middle-aged ladies overdose on sleeping pills, while timid youths commit acts of equally suicidal bravado. And most importantly, virtually everyone proves troublingly eager to be led by anyone who acts like they know what they’re doing, be that Norton, Carmody, or indeed David Drayton. That last is significant, because David, rather like Ben in Night of the Living Dead, turns out to be not quite as good a leader as he seems— which gets us back to that contentious ending I mentioned.

In King’s telling, The Mist didn’t so much end as reach a convenient stopping point, and in the context of the printed page, that works quite well. To draw another Lovecraft parallel, King’s in media res ending provides a workaround for a problem that the earlier author never really solved in his work, the protagonist who somehow records the events that will be his undoing. We never learn for certain what becomes of Drayton and his fellow escapees in King’s version, but we’ve seen enough by the concluding paragraph to predict that it probably isn’t good, even despite the wriggling nightcrawler of hope that he dangles over their heads at the last. In a modern movie, however, King’s ending would look suspiciously like the setup for a sequel, and Darabont was smart to do something else. What he came up with was a curious amalgam of situations that King’s Drayton had envisioned as possible final outcomes, and it manages to be both a happy ending on one level, and the most depressing conclusion imaginable on another. A lot of commentators have condemned the movie’s ending because of what it ostensibly says about how Darabont judges the actions of the characters; if atrocious things happen to people in a movie, or so this line of reasoning goes, obviously that tells us the filmmakers believed they did something wrong, right? Maybe. But hasn’t Darabont spent the bulk of this movie implicitly protesting, via his treatment of Mrs. Carmody, against the notion that adversity is God’s judgement upon those who offend Him? And isn’t it a little strange, in that context, to assume that Darabont— in effect the God of the film’s universe— is passing judgement on the characters he’s borrowing from Stephen King by leaving them in such adversity at the movie’s end? So how about this, then, for a moral, if we’re going to insist upon seeing The Mist as having a moral at all: Sometimes, you can do everything right, and still get everything wrong. God is not in His Heaven, distributing rewards and punishments, and the universe doesn’t actually give a shit how David Drayton comports himself. After all, we’re agreed that The Mist is a film in the tradition of Lovecraft, and an uncaring cosmos that maddens and destroys humans as thoughtlessly as we might crush an insect is another of Lovecraft’s favorite themes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact