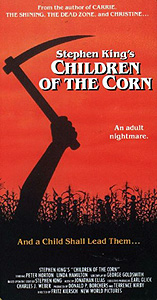

Children of the Corn (1984) *½

Children of the Corn (1984) *½

Long, long ago, in some review or other, I said that I couldn’t recall ever having seen a really bad evil child movie. Well, the time has come for me to eat those words with a big glass of orange juice and a side order of hash browns— or perhaps grits would be the more appropriate side dish, seeing as the film that has brought me to these unpleasant straits is Children of the Corn. The embarrassing part is that I had indeed seen Children of the Corn before— it’s just that I was about fourteen years old at the time, and I either no longer remembered or just plain hadn’t noticed in the first place how lame it really was. Maybe I had allowed my memories to be colored by the Stephen King story on which the movie was based, which while hardly among the author’s best work, is nevertheless lightyears ahead of the celluloid version.

The movie makes two glaring fuck-ups right out of the gate. First of all, it tips its hand immediately by opening with a scene depicting what happened three years ago in Gatlin, Nebraska. Under the leadership of a former child preacher named Isaac (Python’s John Franklin, who also played Cousin Itt in the Addams Family movies of the early 90’s) and a violent creep called Malachai (Courtney Gains, of King Cobra— and as if this needed to be said, two actors in the same movie who have killer-snake flicks in their futures is hardly a propitious omen), the youth of Gatlin rose up one day to murder all of their elders. God told them to, you see. Now admittedly, it’s hardly a secret that evil kids will be in the offing in a horror film called Children of the Corn, but the filmmakers still didn’t do themselves any favors by revealing exactly who the bad guys are and exactly what they’re all about in the very first scene. The other opening-gambit misstep is much more serious, however. The powers that be have added a voiceover narrator charged with stating the obvious. A seven-year-old voiceover narrator charged with stating the obvious. A seven-year-old voiceover narrator who states the obvious with a motherfucking lisp! Nothing good can come of this.

Skipping ahead now to the present day, we meet the newly-diplomaed Dr. Burt Stanton (Peter Horton) and his adoring girlfriend, Vicky (Linda Hamilton, from The Terminator and Terminator 2: Judgment Day). These two are on their way cross-country to Seattle, where Stanton is set to begin his medical career, and what goes on between them this morning in their motel room is just about the most obnoxiously cute thing you’ll ever see two adults do. Let us speak no more of it. Luckily for us, the scene is cut short, for Stanton is on a tight schedule, and there is still many a mile between him and Seattle. In fact, he and Vicky are just a bit short of Nebraska’s eastern border.

Yeah. They’re going to Gatlin, alright, but the way they end up there is more than a little convoluted, and has surprisingly little to do with their own actions. Isaac’s revolution has not been without its dissenters, and three of the Gatlin kids are looking to get out of town. The oldest of these is Joseph (Jonas Marlowe); his two young proteges are Job (Robby Kiger) and Sarah (Anne Marie McEvoy, from Invitation to Hell— a movie beside which Children of the Corn looks like something that deserved to have six sequels), the former of whom is (that’s right) our insufferable lisping narrator. Joseph figures Job and Sarah would just slow him down if he tried to make his escape with them in tow, so instead, his plan is to go it alone during the actual flight through the cornfields around Gatlin, get help from outside, and return to liberate his friends and bring Isaac to justice. That’s not how things turn out, however. Malachai catches Joseph in the fields just a few miles outside of town, slits his throat, and then shoves him out into the highway. That, in turn, brings Joseph to the attention of Burt and Vicky— in fact, Stanton accidentally runs the boy over. Of course, one look at the wound on his neck shows Burt that the kid was already dead or dying when he went under the wheels, but that’s hardly a comfort under the circumstances. It merely means that instead of having just killed a boy by accident, he and Vicky are in the immediate vicinity of somebody else who just killed a boy deliberately. The closest thing to a clue that Burt can find is Joseph’s suitcase, which contains nothing but a change of clothes, some food and water, and a weird homemade corncob crucifix. Stanton puts the dead boy in the trunk, and starts looking for the nearest place from which he might call the authorities.

Burt makes his first try at a little gas station. The attendant (R. G. Armstrong, from The Legend of Hillbilly John and Devil Dog: The Hound of Hell) is almost totally uncooperative, claiming to have no gas, no public bathroom, and no telephone; all Burt can get out of him is that there’s a town called Hemingford (hardcore Stephen King fans will recognize Hemingford, Nebraska— which is never mentioned in “Children of the Corn”— as the home of the centennarian prophetess in The Stand) about 20 miles down the road, and that there’s no point in going to Gatlin, even though it’s much closer, because the people there have all “got religion” and take an intense dislike to strangers. Somebody has gone and switched the road signs, however, and the gas station attendant’s directions to Hemingford lead Burt and Vicky into Gatlin instead. (Would somebody like to explain to me how the goings-on in Gatlin could have remained a secret for three years when its inhabitants have gone out of their way to divert all of Hemingford’s westbound traffic into their town?) Meanwhile, the children of Gatlin finally get around to killing off the attendant, the last adult within striking range whom they had left alive. And no, there really doesn’t seem to be any reason for picking this particular moment to take him out, or for having spared him in the first place— unless maybe the filmmakers needing an excuse for another gore scene counts as a reason.

Anyway, it doesn’t take Burt and Vicky very long to figure out that something isn’t quite right about the little town. For one thing, it’s uninhabited so far as they can see— this is because all the kids are out in the cornfields listening to one of Isaac’s loopy sermons— but the place hasn’t fallen apart sufficiently for it to be very convincing as a ghost town. After driving around in circles for a while in increasing frustration, the two travelers eventually put in at what proves to be the house where Job and Sarah used to live, and where they still sometimes sneak off to play in ways that are officially condemned by their community’s joyless religion. Sarah’s there now, as a matter of fact, but she is most uncommunicative regarding just about everything concerning Gatlin, and the phone in the house is broken. No help there. Burt decides to make one last stab at doing the right thing by finding the Gatlin town hall, stupidly leaving Vicky behind when he does so. Inevitably, while Stanton is walking in on Rachel (To Die For’s Julie Maddalena) in the middle of performing some twisted sacrament upon Amos (John Philbin, from The Return of the Living Dead and Moonbase), the oldest boy in town, Malachai leads a posse out to the house and abducts Vicky. The children of Gatlin, you see, aren’t just a bunch of rabid juvenile fundies who have seen Wild in the Streets a few too many times. Those cornfields surrounding the town are the domain of some horrible supernatural being which they call “He Who Walks Behind the Rows,” and which Isaac has somehow determined is the real One True God. He Who Walks Behind the Rows demands regular blood-sacrifices from his worshippers, routinely in the form of everyone who turns eighteen, but also in the form of any adults from outside who should happen to wander onto the premises. That means Vicky is slated to be fed to the god-monster as soon as the sun goes down, so Burt had better get off his ass and hook up with Job— otherwise, he’ll never become sufficiently well-informed to have a chance of getting himself and his girlfriend out of here, and we in the audience will be denied even the minimal satisfaction of seeing our migraine-inducing narrator finally acquire some actual function in the story.

Try as I might to force it, the part of my mind that handles things like taste and discernment and the appreciation of artistry simply will not accept that some bunch of assholes made six fucking sequels to this turkey over the ensuing seventeen years. Rarely has a less deserving horror movie attained a higher degree of cultural visibility, and I think the really infuriating thing about Children of the Corn is that its creators pissed away an opportunity to transcend the limitations of the original story, making, on the contrary, nearly every mistake that was available to them. The potential existed to create a film that would hybridize the best features of The Bad Seed and The Hills Have Eyes before blindsiding the audience with a Lovecraftian sucker-punch in the final act, but the filmmakers have fallen so far of the mark as to make one wonder if they were deliberately trying to get it all wrong. This is a survival horror tale at heart, and the key to stories of that type is that the protagonists are left to their own devices in facing down the threat. But by introducing Job and Sarah as insider allies for Burt and Vicky, writer George Goldsmith undercuts that central dynamic while simultaneously denying director Fritz Kiersch the one possible means at his disposal to make a group of children seem like a credible threat to two adults. With numbers, unity, and a total information lockout for the good guys on their side, Isaac and his followers could have been plausibly scary. With Job and Sarah playing fifth column, on the other hand, they’re just a bunch of tykes again, no matter how many pitchforks and sickles they’re carrying around. There’s nothing even a little bit scary in this movie until He Who Walks Behind the Rows puts in an appearance at the end.

Muddling and downplaying the religious aspects of the story might be an even more serious screw-up, and having Burt attempt— on two separate occasions!— to engage Isaac’s followers in a theological debate definitely is. In King’s telling, the faith of the Gatlin kids has a certain twisted logic to it. The cornfields have evidently always been the town’s only real industry. The Old Testament— the only section of the Bible fire-and-brimstone fundamentalists actually give a shit about in their heart of hearts, and the only section the Gatlin cult uses— is full of explicit references to the need for sacrifices to maintain God’s favor, and is equally overt about equating that favor with material prosperity. It also treats terrifying miracles as a fact of everyday life. Take that background, throw in a bloodthirsty supernatural entity living in the farmland, communicating with a boy who has long been thought of (and who has become accustomed to thinking of himself) as a conduit for the Holy Spirit, and the cult makes a frightening amount of sense. The movie scarcely bothers with any of that material at all, and openly demotes He Who Walks Behind the Rows to the level of just another monster. Furthermore, he isn’t a very impressive monster, either. The first visible manifestation— a massive hump scooting along under the ground, displacing the soil upward as it moves— is far creepier than it has any right to be, even if it does kind of lead one to expect He Who Walks Behind the Rows to pop out above the surface at any moment and begin grumbling about how he should have taken that left turn at Albuquerque. But then we get what’s supposed to be an indication of the creature’s “awesome” power, and it’s nothing but a big orange cloud on the horizon. Weak, guys. Really fucking weak.

Indeed, the one thing the makers of this movie really did right was to reinvent the personalities of the two main characters from the ground up. I’m really tired of horror movies that revolve around constantly bickering assholes, and that’s just what Burt and Vicky were in the short story. Burt was obtuse, pig-headed, and seemingly willfully unobservant, while Vicky was just about the worst person in the world— the Gatlin cultists couldn’t sacrifice her fast enough to satisfy me. Children of the Corn would have been an extremely hard slog if it had retained the original conception of the characters. As it is, it’s merely a stupid waste of time.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact