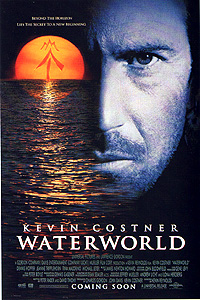

Waterworld (1995) ***

Waterworld (1995) ***

Ever been disappointed by how good a movie was? I went into Waterworld expecting a catastrophe of De Laurentian proportions. For one thing, there was its poor economic performance, with that combination of vast outlays and anemic ticket sales that so often portends a truly epic failure. Waterworld’s reported production cost of $175 million was, at least in unadjusted currency, the greatest in history in 1995, and although its box-office grosses were substantially above that, factoring in ancillary expenses like lab fees, advertising, and shipping for the individual prints would mean that the movie probably just about broke even. Then there was Kevin Costner’s presence as both star and producer, at a time when his burgeoning egomania was generating absurd, expensive farragoes at a rate of about one every fifteen months. But primarily, it was Waterworld’s reputation as a lousy and ungainly white elephant in the worst Hollywood tradition that had me expecting something in the same league as Dino’s King Kong— this was the movie that people were calling Fishtar and Kevin’s Gate, after all. But you know what? Waterworld isn’t half bad. In fact, if you’re willing to set aside the expectation that budget should be commensurate with importance, and accept that this movie was never going to be anything more than Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome on the high seas, then Waterworld starts looking like a commendable attempt to put some of the fun back into “We Have Seen the Future— and It Sucks!” by rescuing it from both the played out desert settings of the previous decade and the increasingly dreary stranglehold of the cyberpunk school that was ascendant in the mid-90’s.

Waterworld’s version of the apocalypse comes courtesy of global warming, and the attendant total meltdown of the polar icecaps. Now in the real world, the worst-case global warming scenario (based on estimates of the volume of water tied up in the icecaps) would put most of today’s coastal plains underwater— a dire enough prospect, given that the majority of the world’s large population centers are situated on coastal plains. That evidently wasn’t quite bad enough for the makers of this movie, though, so Waterworld gives us the complete submersion of all the Earth’s landmass, and never you mind where all the extra water might have come from. Naturally, that puts rather strict limits on the lifestyle choices available to the descendants of such humans as survived the drowning of the world. Most people these days live in atolls, large, free-drifting assemblages of whatever floating junk could be scavenged— boat hulls, caissons, and pontoons, mostly, but if it’ll float, you can bet somebody’s tried to incorporate it into an atoll at some point. Others are drifters or mariners, solitary trader-scavengers roaming the global ocean in small boats powered by sail or paddle. (The exact distinction between a drifter and a mariner— if in fact there is one— is not at all clear.) Still others are smokers, nautical equivalents to the gasoline-dependent brigand tribes of The Road Warrior.

Our unnamed hero (Costner, from The Postman and Sizzle Beach, USA)— let’s call him Gil, just for the sake of being able to call him something— is a mariner with just about the swankest junk-cobbled boat imaginable. This thing has a triple-catamaran hull; yard upon square yard of netting between the hull sections serving as a practically weightless substitute for deck area; dual, pulley-operated, mechanically collapsible lateen sails; a device for recycling urine into potable water; and a battery of swivel-mounted harpoon guns. Q and M between them could not have done better. There’s even a primitive deep-diving rig, enabling Gil to descend to the shallow seafloor where the continents used to be in order to collect stuff that few other drifters ever see, including the rarest commodity in all the world: dirt. Relatively ready access to dirt not only gives Gil incomparable leverage in trading, but also enables him to practice a very limited form of horticulture, currently exemplified by the bonsai-sized lime tree he has growing in a pot on the deck of his boat. One day, while Gil is diving for dirt, another drifter (Chaim Girafi) happens along and sees his unoccupied-looking vessel. A boat like Gil’s would be quite a prize for anyone in his ecological niche, so the second drifter stops to see if it really is derelict, helping himself to Gil’s limes while he waits. He understandably says nothing about that last part when Gil surfaces, mentioning only that he saw an atoll some eight days’ sailing to the east, but Gil will eventually notice that he’s been ripped off. While the two drifters talk, a group of smokers on jet skis spot them, and swoop down to attack. Gil establishes his bad-ass credentials at this point, making short work of the smokers, outmaneuvering the other mariner’s opportunistic attempt to steal his dirt, and wreaking a quick bit of vengeance for his pilfered limes all at the same time. Then he sets an eastward course in the hope that somebody at that atoll has something interesting to trade for the 3.2 kilos of dirt he brought up from below.

In fact, the most interesting thing at the atoll isn’t for sale. The trading post there is run by a woman named Helen (Jeanne Triplehorn, of Basic Instinct and Paranoid), who lives with a studious and inventive old man called Gregor (Michael Jeter, from The Green Mile and Jurassic Park III) and a very slightly prepubescent girl (Tina Majorino) toward whom she takes a more or less parental attitude. Enola is not really Helen’s daughter, though. No one ever explains how, but it seems Helen found Enola somewhere far away when she was just a few years old, and effectively adopted her. Very remarkably for a girl her age, Enola has a tattoo on her back, showing an extremely stylized image of the world surrounded by Chinese characters. Helen and Gregor believe that Enola hails originally from the mythical paradise known as Dryland, and that her tattoo is a map meant to lead the outside world there. Their theory is substantiated by the girl’s habit of drawing things that no one has ever seen (but which we instantly recognize as horses, trees, and the like), seemingly from subconscious memory. Nevertheless, this is not something that they want anyone and everyone to know about; perhaps because of the “coded” nature of the supposed map, Helen and Gregor seem to regard Dryland as their own personal retreat, not to be shared with the rest of the atoll’s rabble. Similarly secret is the means whereby the two conspirators mean to make their escape— the primitive airship that Gregor has been constructing in the atoll tower where they live.

All this sort of trickles out while Gil makes his way about the atoll, getting as much as he can for his big jar of dirt. Similarly, it comes out that Helen and Gregor have been less circumspect than they realize, for a man named Nord (Gerard Murphy) is plainly aware that some connection is supposed to exist between Dryland and the tattoo on Enola’s back. That’s very bad news, because Nord is really a spy for a big tribe of smokers led by a raving lunatic who calls himself the Deacon of the Deez (Dennis Hopper, from Land of the Dead and Space Truckers)— the Deez, in case you’re wondering, being the just-barely-seaworthy hulk of the infamous Exxon Valdez oil tanker, which the Deacon and his followers have been using as their base of operations. The smokers care about Dryland because that oil in the Deez’s bunkers is going to run out one of these days, and when that happens, it will bring their whole way of life to a screeching halt.

By a fortuitous coincidence, the Deacon and his minions attack the atoll just in time for the resultant chaos to get Gil out of an extremely tight spot. You see, it turns out Gil is a little peculiar. He has both webbed toes and gills (yeah, okay— so I didn’t choose his nickname completely at random…), making him a forerunner of the likely next step in human evolution, and as little as the atollers trust outsiders in general, they trust mutants even less. Though the sheriff of the atoll (Zitto Kazann, of Beyond Evil and The Swinging Barmaids) tries his best to avert a lynching, the village elders condemn Gil to death by recycling— essentially, being drowned in the atoll’s compost tank. When the smokers attack, everyone sensibly stops paying attention to Gil, Gregor’s airship launches prematurely with only its inventor aboard, and Helen and Enola acquire both a reason and a free hand to release Gil from the drowning cage in exchange for his getting them the hell out of Dodge. The Deacon and Nord are observant men, however, and they notice soon after the smokers’ victory that the object of the assault has managed to escape. The smokers will be combing the sea for Gil’s boat from now on, and setting traps for him at every opportunity— this on top of the obstacles to survival posed by just trying to exist in an environment that contains things like giant, man-eating porpoise-monsters and a sex-maniac drifter (Kim Coates, from Battlefield Earth and Red-Blooded American Girl) even more thoroughly demented than the Deacon himself.

I really wish I’d gotten around to Waterworld earlier— I could have used some unapologetic retro-Mad Max-ness circa 1995. While it certainly doesn’t stand as the high-water mark (that’s right— I went there) for B-movies made on A-budgets, even in the context of a decade with forgiving standards for such things, Waterworld represents a huge advance over comparable films from the likes of Roland Emmerich and Michael Bay. If nothing else, it uses the right cliches for the job, drawing on the established (if not necessarily proud) traditions of the post-apocalypse action movie in ways that reveal an honest appreciation for the genre. At no point does the movie appear to be ashamed of itself or of its pedigree, and although it breaks no new ground except in terms of its setting, it gives the well-worn material the best treatment it had had in ages. Kevin Costner is perfectly adequate as a sullen, survival-focused antihero, which is much better than he can usually manage in roles that require him to be charismatic and inspiring. An antisocial jerk who almost never speaks except to order people to shut up and keep their hands off of his stuff is a lot more commensurate with Costner’s natural abilities than, say, Robin Hood. Dennis Hopper, meanwhile, is wonderfully cracked as the Deacon of the Deez, and pretty much walks off with the entire film. Sure, nobody’s going to be the tiniest bit surprised to see Hopper playing yet another fucking loon, but his particular brand of craziness is one I never seem to get sick of— probably because it’s too idiosyncratic for anybody else to copy it recognizably. Despite the general light-headedness of the story, there are strands of definite internal logic running through it, such as the implied location of Dryland or the numerous little details proving that screenwriters Peter Rader and David Twohy gave some serious thought to what a society built out of the floating detritus of our own might look like. On a related note, the production design is superb. Rarely has the garbage-tech esthetic been pursued as convincingly as it is here, with every piece of equipment or machinery looking like a second cousin to the tanker truck in Duel. Who knows how Kevin Costner hoodwinked Paramount into spending $175 million on a movie that Luigi Cozzi or Enzo Castellari might have made for about 1% of that sum, but I sure am glad he did.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact