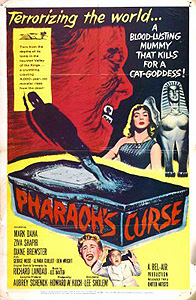

Pharaoh’s Curse/Curse of the Pharaoh (1956) **˝

Pharaoh’s Curse/Curse of the Pharaoh (1956) **˝

I’ve come to the conclusion that there must really be a Pharaoh’s Curse. Now mind you, it has nothing to do with the wrath of the ancient gods against those who desecrate the tombs of Egypt, and it sure as shit wasn’t behind all the bad things that later befell the discoverers of King Tutankhamen’s burial site. No, the real Pharaoh’s Curse is the fearsome black juju that has prevented generation after generation (with only a tiny handful of exceptions) from making a better-than-passable horror flick about mummies. Like I said, there have been a couple of exceptions (Hammer’s The Mummy being the hands-down leader of the pack), but the vast majority of mummy movies over the years have ranged in quality from “eh…” to “get a rope.” This particular entry in the subgenre rates a little better than “eh…”— but not by much.

The year is 1902, and the peasantry of Egypt is in open revolt against its British overlords. (Actually, to talk of “British overlords” is to simplify the political situation in Egypt at the turn of the last century substantially, but I digress.) With anti-British violence on the rise, the military authorities have seen fit to concentrate their forces at the smallest possible number of locations, and to direct all British civilians to seek shelter with the army garrisons. Unfortunately, a few of those civilians happen to be out in the countryside just now, searching the desert for the lost tomb of the pharaoh Ra-Hateb. The authorities want that expedition brought home, and they want it done in such a way as to draw the least possible attention to it— after all, the last thing they need is to get the locals pissed off about infidels tampering with their ancient heritage. As such, any large rescue expedition is out of the question, and the task falls to Captain Storm of the Royal Infantry (Mark Dana). He will be assigned only two men, Sergeants Gromley (Sextette’s Richard Peel) and Smolett (Terrence De Marney, from Confessions of an Opium Eater and Die, Monster, Die!), and what’s more, they’ll also have to bring along Sylvia Quentin (The Invisible Boy’s Diane Brewster), the wife of the American adventurer leading the archeological dig. Just what Storm wanted to hear, right?

Were I Captain Storm, I personally would be more upset that my superiors had somehow screwed up and recruited both of my measly two subordinates from His Majesty’s Comic Relief Brigade, but that’s an altogether different matter. In any event, Mrs. Quentin proves to be one tough lady, which naturally means that she’ll end up melting uselessly into Storm’s arms about halfway through the picture, forsaking the most unfeminine life of adventure that her globe-trotting husband has foisted on her. But for now, it mainly means the three soldiers don’t have to pussyfoot around for her benefit. On the very edge of the desert, though, the party is forced to take on another less-than-welcome hanger-on. When the soldiers respond to a sudden outbreak of the jitters among their horses, they find themselves face to face with a pretty native girl (Ziva Shamir, from Macumba Love and The Giants of Thessaly) who is astonishingly carrying neither food nor water despite her claims of just having crossed the desert. Not only that, Simira (for that is the girl’s name) refuses Storm’s offer of food and drink from his own party’s supplies. When questioned about her business out in the desert, Simira replies that she is searching for her brother, Numar (Alvaro Guillot), who left their village to accompany a party of Westerners on a search for an ancient tomb; Simira says that she must catch up to her brother and his new companions “before it is too late.”

That’s just fine and all, but getting to the Quentin party in any kind of hurry will mean taking the direct route, which Storm is under strict orders not to do. There’s too much bad business afoot in that part of the country to follow a well-traveled path, and so Storm is committed to sneaking around to the site of Quentin’s dig from the other side. And since he also insists (just to be on the safe side) that Simira accompany him, his men, and Sylvia Quentin, that means the girl is just going to have to wait. She doesn’t like that, of course, and as the days of trudging across the wilderness wear on, it comes to seem as though Simira may have some uncanny means of making her companions see things her way. First one of the donkeys carrying the team’s food and water vanishes, leaving only its halter and harness in its place, and does so right under the nose of Sergeant Smolett. Then a scorpion sneaks into Sylvia’s bedroll one night and stings her on the arm; Sergeant Gromley discovers that the medical kit is missing when he goes to get it for her. Interesting that this crisis should develop right when the party was approaching their last chance to get on the short road to the Valley of the Kings and Robert Quentin’s campsite, isn’t it?

Actually, it’s a pity Simira didn’t think to work that mojo earlier, because the events she’s been trying to hurry Storm along in order to prevent are taking place at that very second. While the Egyptian girl’s brother looks on, Robert Quentin (George N. Neise) is brow-beating his colleagues— Walter Andrews (Ben Wright, of Journey to the Center of the Earth and Terror in the Wax Museum), Claude Beauchamp (Robert Fortin), Dr. Michael Faraday (Guy Prescott, from Queen of Outer Space and The Hypnotic Eye), and Hans Brecht (Kurt Katch, whose two previous mummy movies [The Mummy’s Curse and Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy] were much worse than this one)— into helping him pry the lid off an old coffin they’ve found inside the tomb of King Ra-Hateb. It isn’t the king’s, but that sort of thing hardly matters in a mummy flick; open a coffin and you’re fucked, even if it only belonged to the pharaoh’s fluffer. Storm and company arrive on the scene just in time to catch Numar passing out for no apparent reason when Dr. Faraday turns his scalpel on the mummy’s wrappings.

This is where Pharaoh’s Curse gets almost imaginative on us. Rather than just wheeling out a regular old living mummy, it posits a curse that turns one of the tomb-raiders into a living mummy, and sends him to avenge the desecration. Numar sickens rapidly after his unexplained faint, getting more and more leathery and dehydrated with each passing hour. Eventually he rises up and begins going after the men, sucking them dry of blood to sustain his own unlife. Captain Storm and his men are prevented from simply taking their leave of the tomb complex by a combination of three factors. First, Sylvia Quentin is still sick from her scorpion sting, and is in no condition to travel. Second, Robert Quentin refuses to go anywhere until he has found the mummy of King Ra-Hateb himself. Finally, the mummified Numar kills Sergeant Gromley, which is enough to push Storm into the pro-staying camp. Quentin figures the answers to all their questions and the solutions to all of their problems will come to light with the discovery of the royal burial chamber, and he eventually convinces Storm that he’s got the right idea. Of course, that means everyone is going to have to spend an awful lot of time down in the tomb— down in the tomb with the killer mummy.

Pharaoh’s Curse may not raise the quality average for the mummy subgenre to any detectable extent, but it does at least represent a legitimate and fairly successful effort to bring it into line with what was then the state of the horror movie art. 50’s American monster flicks have a distinctive and almost invariable feel and structure to them. You can expect a sizeable amount of foreshadowing in the first act, hints pointing toward all the very bad things that will be happening later. There will usually be at least a ritualistic stab at shrouding the agency responsible for those very bad things in an aura of mystery; even when the true nature of the movie’s destructive force is immediately obvious— even when the title is something like Tarantula or The Deadly Mantis— the filmmakers will usually ask us to play along at some point and pretend we don’t know what’s coming. And most noticeably, monster movies of this vintage are almost always lensed in a style that has no use for old-fashioned atmospherics. In fact, sometimes you get the impression a film was shot by a cinematographer who actively held atmospherics in contempt. The thing is that you expect to see this style in the context of a vaguely sci-fi-ish story about bugs that eat radioactive grain or prehistoric fish-men that have survived unnoticed to the present day in a remote environment. I always find it interesting to see the 50’s monster template applied to subject matter more generally associated with the 30’s and 40’s, when horror movies were all about atmospherics. And while the attempt doesn’t quite gel here the way it does in, say, The Vampire or The Werewolf, it does give Pharaoh’s Curse a little something extra to set it apart from Universal’s older mummy movies and the later Hammer films that they inspired.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact