The Hypnotic Eye (1960) ***

The Hypnotic Eye (1960) ***

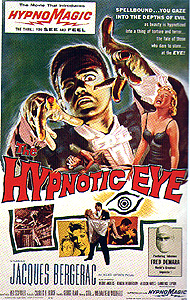

William Castle was only the tip of the iceberg. The gimmick-laden horror films he made for Columbia beginning with Macabre in 1958 demonstrated that it was possible to compete with television from a position of strength, even for producers without the capital necessary for 3-D, Cinemascope, color film, or big-name actors. Castle’s glow-in-the-dark plastic skeletons, seat-cushion-mounted joy buzzers, and insurance policies against death by fright proved that good, old-fashioned hucksterism could create more than enough excitement and curiosity to draw viewers away from the boob tube, and weird publicity stunts became at least a sporadically recurring fact of movie-going life until well into the 1970’s. The ephemeral nature of the gimmicks themselves has served to obscure to some extent just how widespread the phenomenon was (for example, few people today remember that United Artists promised $50,000 to anybody who could prove conclusively that Mars harbored no such creature as the vampiric alien in It!: The Terror from Beyond Space), but there were a few movies from the huckster-horror era that followed Castle’s lead all the way to weaving their gimmicks into the fabric of the film. The Hypnotic Eye is one such picture, milking in the most sensational manner yet seen the same mania for mind-control that had driven Horrors of the Black Museum and The She-Creature. In The Hypnotic Eye, the audience would risk falling under the evil mesmerist’s spell right along with the characters.

In one of the most arresting opening scenes in the annals of cinema, a very attractive blonde woman steps into her apartment’s kitchen with her hair full of lather, apparently intending to rinse herself off in the sink. It isn’t the sink she heads to, though. Instead, the woman switches on one of the burners on the gas stove, and as the camera shifts perspectives to watch her from beneath the ring of blazing gas, she calmly bends over and lowers her soapy hair into the fire. Her placid demeanor evaporates very quickly after that, and she starts screaming loud enough to wake the dead as the flames engulf her head and hands.

Detective Steve Kennedy (Joe Partridge) quickly arrives on the scene to investigate the horrid incident. The burned woman is sufficiently lucid to answer a few questions during the last moments of her life, but she is totally unable to account for her actions. Evidently, she really did believe that she was washing her hair in the kitchen sink, at least until the fire really took hold of her. The opening-scene blonde is by no means the only beautiful woman to mutilate herself horrendously for no apparent reason of late, either. One lowered her face into a spinning desktop fan; another gouged out her eyeballs with a straight razor; a third melted out her tongue with a lye highball. Not one of them understands why she did it, or was even aware of what she was doing at the time. Kennedy knows that there are way too many of these women (eleven altogether) for simple coincidence, but he’s at a loss to find any connection or commonality among them beyond the mutilations themselves. Neither does Philip Hecht, Kennedy’s psychiatrist friend (Guy Prescott, of Pharaoh’s Curse and The Unearthly), have anything very helpful to say on the subject.

The next evening, Kennedy goes with his girlfriend, Marcia Blaine (Marcia Henderson), and another woman named Dodie Wilson (Merry Anders, from House of the Damned and The Time Travellers) to see a stage hypnotist who calls himself the Great Desmond (Jacques Bergerac, from The Fury of Achilles and Strange Intruder). It’s the usual shtick, with Desmond and his T&A assistant, Justine (Allison Hayes, of The Crawling Hand and Attack of the 50-Foot Woman), choosing audience volunteers and making them do ridiculous and/or seemingly impossible tricks for the amusement of the crowd. Kennedy contends that all of Desmond’s “volunteers” are in fact accomplices, placed by the hypnotist and trained to perform whatever routine they run through while supposedly entranced, but his glib dismissal springs a leak when Dodie gets called up to the stage. Whatever else she may be, Dodie is clearly not one of Desmond’s ringers, so her physics-defying behavior up on the stage would seem to attest that there’s something legitimate about the hypnotist’s act after all. Desmond’s hypnotic powers become even more difficult to discount when Dodie descends from the stage and tells her friends that she can remember neither anything she did up in front of the audience, nor what it was that Desmond whispered to her before releasing her from her trance.

It’s that whispering that we’ll be thinking about most when Dodie goes home that night and washes her face with sulfuric acid— well, that and where in the hell she could have gotten her hands on a bottle of concentrated acid in the first place. This is the point at which Steve Kennedy exposes himself as an extraordinary dullard, for he is unable to make the connection between Desmond’s conspiratorial whisper and Dodie’s motiveless self-mutilation, even after Hecht explains to him the concept of post-hypnotic suggestion. Marcia, on the other hand, is quicker on the uptake, and she takes it upon herself to pay another visit to the theater where Desmond performs, hoping to find some sort of incriminating evidence against him. Of course, since Marcia’s brilliant plan is to get herself called to the stage to be hypnotized, she isn’t exactly Nobel Prize material, either. At least she’s smart enough to shut her eyes when Desmond whips out the titular Hypnotic Eye— a little stroboscopic gizmo in the form of a plastic eyeball that he surreptitiously waves in the faces of his volunteers. Marcia is thus not really entranced when Desmond feeds her a post-hypnotic suggestion to meet him backstage at midnight, and she becomes convinced that she’s found (or is about to find) the key to all the mysterious maimings.

Now remember what I said about Kennedy being a dullard? Well get this: Not only does he see nothing wrong with his girlfriend appointing herself as the bait in an extremely risky entrapment scheme, he gets all jealous and pissy when Marcia (having inadvertently hypnotized herself by staring into the Hypnotic Eye when she found it in the drawer of Desmond’s dressing table) accompanies Desmond first to the world’s most annoying beatnik club, then to a fancy restaurant, and finally to her apartment. What? Did it not dawn on Steve that Marcia might have to play along with whatever game Desmond had concocted in order to turn up some sufficiently damning evidence? Did it not occur to him that just maybe she might wind up under the scheming sleazebag’s power despite her best efforts to the contrary? In fact, Kennedy works himself up into such a jealous fury that he nearly abandons Marcia to a full-body disfigurement by scalding when Desmond’s assistant walks in on her “boss” and his date, orders the mesmerist out of the flat, and commands the entranced Marcia to take a shower in near-boiling water. Only a sharp intervention from Hecht (who had accompanied Kennedy on the stakeout) persuades the moron detective to go up to the apartment and see if Marcia is alright. Justine tries to fend Steve off with a cock and bull story about being an old roommate of Marcia’s, but Kennedy is at least bright enough not to fall for that. Even when Marcia (still in her trance) comes to the door to corroborate the story, Steve sees the giant hole through the middle of the lie— Martha never went to college or to boarding school, and therefore could never have acquired any former roommates. Justine makes her exit down the fire escape while Kennedy is talking his way through her bullshit at the front door.

The night’s events raise far more questions than they answer, however. Obviously Desmond and Justine are behind the mutilations, but why? What’s in it for them to have a bunch of beautiful women disfigure themselves? Could there be some hitherto unseen history tying all of the victims together? Probably only Desmond and Justine know the real answers, and that means Kennedy will soon be attending another show.

It is during this final show that Desmond turns his hypnotic powers upon the real-world audience. In retrospect, this was not nearly as smart a move as it might have seemed at the time. Up to this point, The Hypnotic Eye has had its problems (the biggest being the hero’s astonishing obtuseness), but it’s handled itself quite well on the strength of a compelling mystery, an interesting pair of villains, and some exceptionally gruesome makeup effects. But then Desmond commands us all to gaze into the Hypnotic Eye, and the film comes screeching to a halt. Worse, in fact— it plows at top speed into a telephone pole, pushing what’s left of its engine right through the firewall and into the front seat. For some ten interminable minutes, Desmond subjects both his audiences to a battery of hypnotic exercises that merely leave me wondering, once again, if people in the late 50’s and early 60’s could possibly have been so pitifully susceptible to suggestion. By the time the story gets going again, The Hypnotic Eye has worn out a lot of its welcome.

It didn’t have to be that way. The audience-hypnosis card could have been played much earlier in the film (Desmond’s very first appearance would probably have been the ideal place for it), bringing in the all-important gimmick without obliterating the story’s momentum right on the verge of the climax. Then we’d have the histrionic silliness nicely out of the way, enabling us to appreciate the more subtle aspects of Jacques Bergerac’s villainy. Even more importantly, Allison Hayes wouldn’t have to put one of the era’s truly great bad-girl performances on hold for an entire reel while Bergerac attempted to convince the viewers that they were helpless to stop themselves from acting like idiots at his command. There’s enough that works in The Hypnotic Eye to make it worth my while in spite of the grievously botched climax, but this is one of those times when I’m not sure my reaction can safely be generalized to anybody else.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact