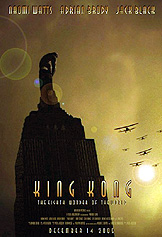

King Kong (2005) **½

King Kong (2005) **½

Flush from the staggering box-office success of his highly overrated Lord of the Rings trilogy, Peter Jackson could probably have talked any studio in the world into backing him on any movie he wanted to make. Even so, I doubt I was the only one to be taken aback at the announcement, after The Return of the King finished its triumphal tour of the theaters in 2003, that Jackson planned to follow up by remaking King Kong. Particularly in light of Dino De Laurentiis’s stupendously botched attempt from 1976, remaking King Kong is just about the one thing I can think of that might be even more hubristic than filming a three-part, nine-hour, live-action version of The Lord of the Rings. The good news is that Jackson has acquitted himself far more favorably than Dino’s people did 29 years before him. The bad news is that the new King Kong still comes nowhere near matching the original as a total package, hamstrung as it is by a lethargic pace, a marked tendency toward gross visual overindulgence, and a pointlessly hypertrophic three-hour-plus running time.

It’s hard to say which defect contributed most to the failure of the earlier remake, but setting it in what was then the modern day was surely one of the biggies. Jackson wisely sidesteps that trap, returning the story to the early 1930’s where it belongs. A rather nicely done montage juxtaposing the upscale gaiety of a pre-urban blight Times Square with the squalid misery of a Hooverville not too far away establishes the scene before we get down to business— “business” in this case meaning the introduction of struggling vaudevillian Anne Darrow (Naomi Watts, from The Ring and The Ring Two) and her similarly struggling fellow singer/dancer/comedians. Nobody has any money, so nobody’s spending any money, so the director of Anne’s company hasn’t been able to pay any of his employees in weeks. What’s more, the director also can’t afford to pay the rent on the theater, and the owners have just decided to pull the plug; when Anne and her colleagues show up for work the day after a particularly ill-attended performance, they find their landlords’ agents slapping up “Closed until further notice” signs all over the theater’s exterior. The rest of the troupe is pretty much screwed, but Anne thinks she has an out. Her hero, playwright Jack Driscoll (Adrien Brodie, of The Village), is casting his latest drama, and Anne has been making the biggest possible pest of herself with Driscoll’s casting director. Surely one more good, hard shove is all it’ll take to get her in the door, right? Wrong. The play is fully cast already, and Anne is dismissed with nothing but the scribbled address of another theater where an attractive but desperate performer such as herself might be able to pick up a few days’ work, pocket a few dollars, and never look back. You got— it’s a strip club.

Meanwhile, Carl Denham (Jack Black, from Mars Attacks! and I Still Know What You Did Last Summer), a producer/director operating in the novel field of motion pictures, is in equally hot water. The heads of the studio for which he works have been funneling lots of money they don’t exactly have into his latest project, and all they currently have to show for it is a good eight reels of wildlife footage. Not only that, Denham has just informed them that he has scrapped the original script and is now in the process of outfitting a ship to take him and his cast and crew to an island in the tropics for an extended location shoot. He can’t say just where that island is, because it hasn’t officially been discovered, and Denham knows of it only because he has come into possession of a map sketched by a shipwrecked mariner who once saw it, but he’s certain the uncharted island will afford the most exciting shooting locations ever seen by the eye of man. Needless to say, this is not what the moneymen wanted to hear. After a few minutes’ discussion, the studio bosses decide to kill off Denham’s film and sell the currently extant reels as stock footage. Denham (who has been eavesdropping on the conversation) will have none of that, however, and by the time his overlords are ready to inform him of their decision, he and his assistant, Preston (Colin Hanks), have taken the footage and run, determined to finish the movie no matter what the odds. They can’t just drive to the docks and ship out, though, because their leading lady has just quit in response to the news that she would be expected to travel halfway around the world to a place that isn’t even on the map, meaning that Denham will have to scramble to come up with an understudy on short notice— and an understudy slight enough to wear the original starlet’s costumes, at that.

To the surprise of absolutely nobody, that understudy ends up being Anne Darrow. Denham spots her out in front of the strip club, as she disgustedly crumples up the address given to her by Driscoll’s casting director and walks away. Knowing that he’s found his girl, Denham follows her, arranging to be on the scene in time to rescue her from arrest when she gets caught shoplifting an apple from a storefront market. Anne resists the director’s pitch at first, but changes her tune when Denham mentions the name of the man who is writing the script for the picture. That’s right— it’s Jack Driscoll. With the prospect of working from a screenplay by her favorite writer sweetening the deal, Anne signs on for Denham’s movie, and before she knows it, the director is introducing her to the crew of the SS Venture, the ship aboard which she’ll be sailing to parts unknown. It’s a big bunch of men, but the only ones we really need concern ourselves with are Captain Engelhorn (Thomas Kretschmann, of Resident Evil: Apocalypse and Blade II), First Officer Hayes (Evan Parke, from Planet of the Apes and Nightstalker), Lumpy the cook (Andy Serkis, who was the on-set stand-in and motion-capture model for Gollum in the Lord of the Rings movies, and who is similarly the man behind the ape in King Kong), and Jimmy (Jamie Bell), the teenage boy who exists mainly to serve as a recipient of his elders’ platitudes. Denham, of course, has his own crew: cinematographer Herb (John Sumner, from The Tommyknockers and The Frighteners), sound recordist Mike (Perfect Creature’s Craig Hall), leading man Bruce Baxter (Kyle Chandler), and some guy named Harry (Mark Hadlow, from Strange Behavior and Warlords of the 21st Century), whose function I’m not at all clear on. Oh— and Driscoll, of course. Jack doesn’t plan on setting sail for the opposite side of the globe, but Denham contrives to keep him aboard the Venture until Engelhorn has his ship underway. Driscoll is only marginally less incensed than Denham’s bosses, who had sent the cops after him in response to his theft of the wildlife footage shot on their dime, and who have just come up empty-handed.

The long, long voyage across the sea is devoted mainly to one form of exposition or another, with a little bit of character development thrown in to keep things from becoming too monotonous. We learn that Engelhorn is in the twin businesses of smuggling guns and capturing exotic wildlife. We learn that Denham’s uncharted isle is known locally as Skull Island, and that it has a truly horrendous reputation. We learn that Hayes wants Jimmy to get himself an education so that he won’t be stuck sailing on a tramp steamer for the rest of his life. We learn that Anne and Jack are in love with each other, but are both too chickenshit to say anything about it. And most of all, we learn that when you have a $200 million budget, there’s no incentive whatsoever to economize on film stock by eliminating useless, dramatically unproductive scenes.

Eventually, though, the Venture finally does reach Skull Island, essentially by accident and after Engelhorn has already decided to abort the search and drop Denham off at the nearest port to face the wrath of the authorities. The ship sails into a dense fogbank, and quickly becomes hung up on one of the numerous pinnacles of rock that litter the sea surrounding the island, meaning that they’re pretty much stuck there whether Engelhorn likes it or not. The next morning, while the captain and his crew scramble to get the Venture seaworthy again, Denham and the others pile into one of the ship’s boats and go ashore. They find themselves on a rocky peninsula covered with the ruins of an ancient city and separated from the rest of the island by an immense wall of badly decayed stonework. At first, Denham believes the ruins to be uninhabited, but then his party is surrounded and attacked by the savage islanders. Several of his people are injured and Harry is slain before the Venture crew comes to the rescue like the world’s scruffiest cavalry and drives the natives off. Our heroes have not seen the last of the islanders, however, for their apparent leader, a fantastically aged woman who appears actually to be made of wrinkles, has determined that something called “Kong” would be very interested in Anne Darrow. A raiding party of islanders boards the Venture that night and abducts the girl; by the time Driscoll and Engelhorn have organized the crew in response, Anne has already been tied to an altar on the far side of the wall and carried off into the jungle by a 25-foot gorilla.

Having been through this twice already before, I’m pretty sure we all know more or less what’s coming, in outline if not in detail. Jackson and his compatriots make an interesting attempt to steer a middle course between the flat-out monster movie approach of the original and the interspecies love story of the previous remake. The Skull Island of today resembles that of the early 1930’s in that it is home to an admirably varied bestiary of skillfully realized prehistoric monsters against which the movie pits Kong, Anne, and the rescue party from the Venture. Denham, Driscoll, and the crew of the ship face a sauropod stampede; a marauding pack of relatively small, swift, carnivorous dromeosaurs; a squadron of bat-like monstrosities; a ravine full of killer arthropods; and naturally Kong himself. The vast majority of the supporting characters who have been given names die over the course of the trek through the jungle, and Denham loses all of the film for which he has traded the lives of so many of his friends. Anne is menaced by ghastly, yard-long centipedes, crocodile-like scavengers roughly the size of a large pickup truck, and most impressively a trio of Tyrannosaur-like theropods from which Kong rescues her in the film’s most overblown battle royale. The incident with the dinosaurs changes the way Anne sees the gigantic ape, so that by the time Jack catches up to her on the cliff-face that serves as Kong’s lair, she’s prepared to defend Kong against Denham and Engelhorn’s scheme to capture him and bring him back to New York for exhibition. Naturally, Anne is not successful in her efforts to deflect the men’s plan, and though it takes just about all the chloroform Engelhorn has in the Venture’s hold, Kong is eventually subdued.

It is in the final New York phase of the story that this King Kong hews closest to the plot of the 1933 version, but there are a number of interesting inversions of the familiar tale along the way. Most tellingly, Anne seeks out Kong after the giant gorilla escapes from Denham’s tawdry Broadway presentation, and willingly accompanies him even to the top of the Empire State Building. And in a commendably realistic touch, the decision to send a flight of airplanes to shoot Kong off of the world’s tallest man-made structure takes place totally out of our sight, being made completely without reference to any of the characters with whom we have spent the past two and a half hours or more.

Most movies have an obvious overall quality level from which few of their individual aspects stray very far. A film that is excellent as a whole will typically be excellent in most of its particulars, while one that is bad or mediocre in sum will generally exhibit badness or mediocrity in the bulk of its constituent elements. Not so with Peter Jackson’s King Kong. With King Kong, I am forced to throw up my hands and declare it moderately decent as a mean value, even though there isn’t a single thing about it that can fairly be so described, save the performance of its leading lady. In this film, the awe-inspiringly brilliant is lined up alongside the desperately, piteously lame on very nearly a one-for-one basis— for every moment that left me paralyzed in sheer amazement, there was another that had me rolling my eyes in exasperation, and precious little stands in between the two poles.

Nearly everything that can be counted as an upside has something to do with Kong himself. Those who marveled at the combination of Andy Serkis’s acting and the wizardry of the Weta computer graphics team in the Lord of the Rings movies will be absolutely floored by what the same pairing yields in King Kong. Rick Baker’s 1976 Kong was convincing only as a man in a high-quality gorilla suit; the Japanese Kongs of the 1960’s couldn’t even manage that. Willis O’Brien’s 1933 rendition, meanwhile, was convincing as a character, but could never be mistaken for anything but a movie monster brought to life by crafty special effects. The new version gives us, for the first time, a Kong who is convincing as a gorilla. Reputedly, Serkis prepared for his performance as Kong’s motion-capture model by closely observing gorillas in both a London zoo and a wildlife preserve in Rwanda. All that homework pays enormous dividends, and with the exception of a few rather video-gamey moments during the most intense action scenes (which presumably called for acrobatics that were beyond Serkis’s physical capabilities), it’s easy to forget that that isn’t actually an ape on the screen.

Equally important— and equally impressive— is what Jackson and his fellow screenwriters have done with the relationship between Kong and Anne Darrow. Despite what Carl Denham had to say on the subject, there really was no relationship as such between the woman and the ape in 1933; Kong was interested in Anne for some inexplicable reason of his own, while she regarded him solely as a threat from the second she laid eyes on him until the second he plummeted from the top of the Empire State Building. Nevertheless, the mostly non-existent beauty-and-beast angle of the King Kong story has taken root in the popular imagination to such an extent that a straightforward monster-victim dynamic would never fly today. The 70’s remake made the disastrous, ridiculous mistake of positing what can only be described as a full-blown romance between Kong and Dwan (as the Anne Darrow character was called that time around). This latest rendition does something much smarter, however. Some of you may recall the story of Koko, the lowland gorilla whom Dr. Penny Paterson trained to communicate using American Sign Language beginning in the 1970’s. Among Koko’s more highly publicized exploits was her adoption of a tabby kitten, upon which she bestowed the rather puzzling name “All Ball.” Simply put, Peter Jackson’s Kong is Koko, and Anne is the kitten. Kong is plainly the last of his species. (A pan across the collection of giant gorilla skeletons outside Kong’s lair is one of this movie’s more poignant shots.) The graying fur on his back, the tracery of scars covering his body, and the broken-off fang in his lower jaw show us that he has lived a long and difficult life. There’s no escaping the conclusion that Kong must be almost unendurably lonesome and unhappy, with little or nothing to divert him from his solitary struggle for survival except the sadistic pleasure of dismembering his periodic sacrifices from the islanders. Anne, however (apparently in a desperate attempt to distract Kong from killing her), convinces him that she’d be more amusing alive— after all, a gorilla isn’t a whole lot less intelligent than an exceptionally stupid human, and what could be more appealing to such a mentality than a tiny little creature that performs elaborate vaudevillian pratfalls on command? And having refrained from killing Anne, Kong quickly comes to recognize how keeping her around would fill the emotional void of his embattled existence. Anne, for her part, wants nothing more at first than to escape from Kong’s clutches until he heroically risks his own ass to save her from a group of hungry dinosaurs. In short, both Anne and the ape have reasons for the affection that develops between them, and that affection is consistently portrayed in a manner that squares with the sort of bonds that can develop between humans and animals in the real world. Nor does the new King Kong ever lose sight of the fact that Kong is an animal, and as such is capable of terrible outbursts of violence when he doesn’t get his way.

On the other hand, King Kong is grievously flawed, structurally speaking, and it is littered throughout with seriously compromising “Oh, please!” moments. With a total running time of about three hours and ten minutes, the present remake is not only substantially longer than the already flabby 1976 version, but spans very nearly double the original’s hour and forty minutes. Twice as long as the original is also twice as long as this movie has any excuse to be, and what’s worse, Jackson’s King Kong comes by its excessive duration by dragging out each individual scene to approximately twice its optimal running time. To cite two especially glaring examples, both the sauropod stampede and the battle between Kong and the theropods start off strong, but go on and on and on after their purpose has been served, becoming steadily sillier with each unnecessary moment spent on them. The dinosaur fight eventually degenerates into a fucking trapeze act, for the love of God! Worse still, the entire first act is excruciatingly dull, and is heaped high with only intermittently successful in-jokes and absolutely wretched excuses for character development— much of the latter being devoted to characters who have precisely zero impact on the story! King Kong came within an ace of becoming the only movie I’ve ever walked out on when the First Officer Who Serves No Narrative Function began quoting at length from Heart of Darkness to the Adolescent Deckhand Who Serves No Narrative Function Either.

First Officer Hayes also figures in a sterling example of the second big problem with King Kong, the innumerable little details that just slap you in the face with their obvious wrongness. You see, Hayes, in case I haven’t mentioned this yet, is black. The rest of the Venture crew (with the exception of Lumpy’s briefly glimpsed Chinese kitchen sidekick) is all white, and Captain Engelhorn is a German. King Kong, I remind you, is set in 1933. There is no way in hell a bunch of white guys would have stood for taking orders from a black man in 1933, and the notion of a German captain sailing with a black second-in-command in the same year that Hitler was elected chancellor is even more preposterous! Similarly, Anne and Jack seem to be totally unaware of the fact that they’re more than a thousand feet in the air during their concluding reunion embrace at the summit of the Empire State Building— Anne even gets up on her tip-toes and leans all of her weight onto Jack when they kiss! The first theropod to attack Anne does so even though it’s just settled down to a meal far more satisfying than any she could provide. The otherwise brilliant new version of the original’s much-speculated-upon spider pit scene is marred by the magical precision with which the untrained Venture crew are able to wield their Thompson submachine guns, weapons so grossly inaccurate that soldiers to which they were issued were routinely instructed to aim for their opponent’s left kneecap in order to score a lethal upper-torso hit. During the big dinosaur smackdown, I counted five separate occasions on which Kong should certainly have lost a limb, and Kong makes an incredibly stupid move early in the initial one-on-one grapple that ought to have left him kneeling in the dirt with his guts coiling out into his hands.

Then there’s the enormous missed opportunity represented by the natives of Skull Island. Any treatment even faintly resembling the one from the 30’s would be completely unacceptable today, but Jackson, to his credit, resists the temptation to overcompensate by taking the equal-and-opposite Noble Savage route. Instead, his portrayal of the islanders looks very much like something out of an Italian cannibal movie, making the humans of Skull Island as dangerous in their way as the outwardly monstrous fauna on the other side of the wall. Unfortunately, the islanders never live up to their potential, because they simply vanish from the movie after leaving Anne out to be collected by Kong. As in the De Laurentiis version, the natives aren’t even in evidence during Kong’s rampage through their settlement immediately prior to his capture.

Finally, Jackson’s King Kong reproduces a feature of the original that would have been better left by the wayside— the lackluster performances from just about everybody who has neither a simian ridge nor a body covered almost completely in a dense pelt of black fur. Naomi Watts is adequate as Anne Darrow, but she’s as good as it gets. Evan Parke and Jamie Bell never do anything of value with all the time Jackson wastes on their characters. Kyle Chandler is perfectly believable in the part of a bad actor, but that’s a double-edged compliment if ever I’ve given one. Adrien Brodie as Jack Driscoll is a boring non-entity more notable for his colossal and distractingly crooked honker of a nose than he is for his supposed acting. And Jack Black really ought to stick to comedy. Not that I have any particular memory of him excelling in a comedic role, mind you, but his foray here into the realm of the relatively serious gives me a whole new appreciation for the charms of Robert Armstrong, the mostly inert lump who played Carl Denham the first time around.

All in all, King Kong deserves the curiously polarized reviews it’s been getting. The good stuff is great beyond my wildest, most blatantly unrealistic hopes. The bad stuff sucks beyond my most churlish, mean-spirited worries. On the balance, it manages to be a mediocre film even though there’s next to nothing mediocre about it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact