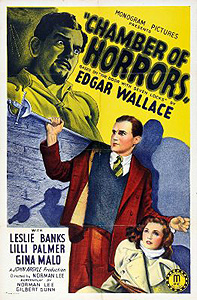

Chamber of Horrors/The Door with Seven Locks (1940) ***

Chamber of Horrors/The Door with Seven Locks (1940) ***

Again I must begin by calling upon you to reign in your excitement and take a closer look at the release date. Sadly, this is not the notorious TV pilot which was released to theaters after it failed to attract any network interest— the one with the Fear Flasher and the Horror Horn. Rather, this Chamber of Horrors was one of the first horror-ish movies released in Great Britain after the Board of Film Censors lifted its mid-30’s ban on the importation of such things. Though that ban technically affected only foreign films, it had cast its shadow over domestic productions as well. Would-be horror directors in the Isles at that time were understandably a bit cagey about working in a genre which faced such strident disapproval that official government action was taken to keep Britain free of its influence, and they took care to avoid dealing too directly with themes that the BBFC found particularly offensive in the preceding decade. The supernatural especially was considered suspect, and thus it was that the great bulk of British horror films in the early 40’s would be better classed as mysteries, gussied up with just enough hints of the macabre to evoke fond audience memories of earlier American and Continental imports without raising too many red flags at the censor board’s offices. The Brits were well placed to pursue such a strategy, too, for they had, in the writings of Edgar Wallace, a seemingly limitless supply of high creep-factor mysteries with a big enough fan-base to make movies adapted from them virtually risk-free at the box office. The Door with Seven Locks (known as Chamber of Horrors in the United States) was one of many British Wallace adaptations to see release in the late 30’s and early 40’s, and while it reputedly retains fairly little of the original novel, it certainly works well enough on its own terms.

As is so often the case, we begin with a very rich man on death’s doorstep. Lord Charles Francis Selford (Aubrey Mallalieu, from The Fatal Night and The Demon Barber of Fleet Street) has gathered his associates to his deathbed to give them all a few final instructions in carrying out his last will and testament. Most of his vast fortune will be inherited by his eleven-year-old son, John, with the stipulation that it will devolve upon John’s Canadian cousin, Judy, should anything happen to the boy before he reaches the age of majority. However, certain extremely old and extremely valuable jewels are to be shut up with Lord Selford’s body behind the septuple-locked door of his tomb in the old family mausoleum, to be removed only to serve as a gift from beyond the grave to whatever woman John eventually marries. The seven keys that will open this tomb are to be placed in the custody of Selford’s solicitor, Edward Havelock (David Home, of Spaceways). John shall be put in the care of his longtime tutor, Luis Silva (Juggernaut’s J. H. Roberts). Finally, each member of Selford’s household, along with Havelock, Silva, and Dr. Manetta (The Most Dangerous Game’s Leslie Banks), Lord Selford’s trusted physician, will receive a little something for themselves.

Ten years later, it looks as though things have not gone quite according to plan. Young John has never really taken up residence at the family manor, having left it in the hands of Dr. Manetta while he goes carousing around the European continent. What’s more, Silva, when next we see him, is nervously writing in his diary concerning a decade-old crime about which he feels he can no longer keep silent. He composes a letter to Judy Lansdowne (Lilli Palmer, later of Night Child and The Finishing School), the fallback heiress to the Selford estate, and mails it off to her together with what can only be one of the keys to Lord Charles’s tomb— a key which Silva shouldn’t even possess in the first place. When Judy gets Silva’s letter, she and her youthful aunt, Glenda Baker (Gina Malo), come over from Canada to see what’s going on. The eventual meeting between Judy and Silva occurs at the nursing home to which the old man has been committed, but before Silva has a chance to tell the girl anything more than what was written in the will, someone hiding behind the painting of Juan de Torquemada that rather incongruously adorns the wall opposite his bed kills him with a shot from a silencer-equipped pistol. The panicked Judy rushes to tell the matron of the nursing home (Cathleen Nesbitt) what has happened, but when she ushers the woman back into the room, there is no sign of Silva’s body inside it, and the matron tells her that the room hasn’t been occupied in months. In fact, the nursing home is scheduled to close that very day, and currently houses no patients at all! Of course, there’s one thing we’ve picked up on that is hidden from Judy for the moment, which makes the whole situation seem even more sinister than it would to begin with— that “matron” looks a hell of a lot like Ann Cody, the late Lord Selford’s old housekeeper.

Having been dumped unceremoniously into the deep end of a deadly mystery, Judy sensibly goes straight to Scotland Yard, where she tells her story to Inspector Cornelius Sneed (Richard Bird) and a second detective named Richard Martin (Romilly Lunge). Martin isn’t technically a cop, as he was just in the process of resigning when Judy walked in, but he takes a strong interest in the case, and will end up doing far more to solve it than his still-officially-employed colleague. The first stop on the itinerary of investigation is the office of Edward Havelock, where it is discovered that not just one, but all seven of the keys to the Selford tomb have been snagged from the locked coffer in which they were supposedly stored. And no sooner do Martin and Miss Lansdowne return to the rented flat where she and Aunt Glenda are staying than they discover a burglar rifling the furniture in search of the key Silva sent to Judy. The burglar and his accomplice don’t find the key, but they do succeed in overpowering Martin and escaping. And as we see them drive off, we notice that the would-be thieves are none other than Selford’s former butler, Craig (Michael Gough lookalike Robert Montgomery), and another Selford hanger-on by the name of Tom Cawler (Phil Ray).

Once Judy, Glenda, and Martin take the investigation to Selford Manor, it becomes increasingly obvious that virtually no one in this movie can be trusted. Dr. Manetta’s collection of Spanish Inquisition torture equipment (from which the movie’s American title presumably derives) is the least of anybody’s worries. Just about every crime in the book— burglary, forgery, impersonation, kidnapping, murder, grave-robbing— will be committed or attempted before it’s all over, the ultimate aim being to keep Judy and her associates from opening the tomb and learning thereby a secret that would put her in possession of all the lands, titles, and movable possessions of the Selford family, leaving a startlingly wide circle of conspirators in the lurch. And though those conspirators are far from being a harmoniously cooperative bunch, they’ve still got a clear enough vision of their own best interests to make Judy’s visit to Selford Manor an extremely dangerous one.

It may not be a true horror film, but it’s easy to see why Chamber of Horrors was marketed that way, especially in America. The movie has enough gothic atmosphere to make Dracula himself feel right at home, and the convincingly moody look of the film belies its comparatively miserly budget. Beyond that, there are a number of points at which its subject matter sticks its head up above the fence that separates the territory of horror from that of the mystery story, and briefly contemplates vaulting over to the other side. For example, there’s a scene involving Dr. Manetta’s vintage iron maiden that wouldn’t have seemed out of place in Universal’s The Raven or The Black Cat.

That’s not to say that hardcore mystery fans are left out in the cold, however. Chamber of Horrors makes for a much better— and much more honest— example of the genre than just about anything being made on a comparable budget in Hollywood at the time. The plot against Judy Lansdowne is good and complicated, but it never strains credulity and best of all, the answers to all the big questions come into view in a gradual, believable manner. There’s the traditional “how I did it” speech from the main villain at the end, to be sure, but it isn’t really necessary, serving mainly to confirm suspicions that the heroes have already arrived at, and to fill in a couple of blanks regarding minor technical details. That scene is also noteworthy for happening under circumstances in which it is reasonably plausible that the villain would feel moved to spell everything out. Nor does Chamber of Horrors exhibit a cheater solution of the Arthur Conan Doyle variety; all the clues are laid out fair and square, so that the audience can play right along with the detectives. But you know what the most remarkable thing about Chamber of Horrors is? The comic relief occasionally manages to be legitimately funny! When have you ever seen that before?!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact