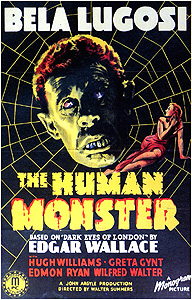

The Human Monster/The Dark Eyes of London/Dead Eyes of London (1939) **

The Human Monster/The Dark Eyes of London/Dead Eyes of London (1939) **

If the number of totally unrelated European horror films whose German-language titles make spurious reference to it is any indication, The Dead Eyes of London was one of Edgar Wallace’s most popular novels. The first film adaptation, The Human Monster (which goes by The Dark Eyes of London in its home country, and by Dead Eyes of London in Continental Europe), was the last British horror movie to see release before the outbreak of World War II, and nearly the last pure horror effort of the British film industry until after the war’s end. Small wonder that, considering that The Human Monster was also the first film to get slapped with the Board of Film Censors’ new H-certificate, a rating devised expressly to discourage the creation of horror movies by subjecting them to even more stringent restrictions than the old A-certificate had imposed. A-certified movies could not be seen by anyone under the age of sixteen unless they were accompanied by a parent or guardian. The H-certificate, on the other hand, limited admission to adults only. Children and adolescents up to fifteen years of age were to be turned away no matter who was along to chaperone. And as its name suggests, it was issued solely to pictures which the board believed crossed what today seems like an absurdly low threshold of horrific content. That said, if any contemporary horror film merited such certification, it was The Human Monster. Even by American and Continental standards, this was extremely strong stuff for 1939, and this movie ought therefore to have become an unheralded highlight of Bela Lugosi’s career— and I mean for reasons other than the fact that it was the only seriously-meant fright film he ever made in the Isles. Unfortunately, that atypically bracing and hard-edged horror is all but overwhelmed by some of the most wretched and insufferable comic relief you’ll ever lay eyes on.

The Human Monster announces its presence with authority, beginning with a montage of dead bodies washing up on the muddy banks of the Thames. The BBFC guys must have had heart attacks when they saw that! Only slightly less bothered by the parade of corpses is CID bigwig Inspector Walsh (Bryan Herbert). Circumstantially, the deaths all look like accidents or suicides— drowning the cause of death, no sign of robbery or battery, no apparent connection between the stiffs themselves— but Walsh isn’t so sure of that. There are just too many of them, and they’re turning up in too tightly defined an area not to set off Walsh’s policeman’s instincts. At the very least, he wants his men to go around to all the insurance agents in town, and see who might have benefited from all these deaths.

Lieutenant Larry Holtz (Hugh Williams) gets assigned, among other things, to check out the Greenwich Insurance Company, and because the boss doesn’t like him much, it will also fall to Holtz to babysit an American cop who is coming over from Chicago as an extradition escort for forger Fred Grogan (Alexander Field). It is because Holtz is so busy picking up Grogan and Lieutenant O’Reilly of the Chicago Police Department (Edmond Ryan) that he misses something over at the Greenwich office that he might find very interesting. Dr. Theodore Orloff (Lugosi), the ex-physician who owns the company, is meeting with a client of his to discuss an extremely large loan. It is never revealed just what Henry Stuart (Gerald Pring) needs the £2000 for, but the only way he can guarantee the loan is by signing over his life insurance policy with Greenwich to Orloff himself. The reason Holtz might like to know about this transaction is that, as he will soon learn, just about all of the people Scotland Yard’s men have fished out of the Thames lately bought their life insurance from Orloff. (And yes, this is indeed one of the sources from which Jesus Franco got the idea for his Dr. Orlof. As we shall see a bit later, this guy even has a humongous blind henchman to do the dirtiest of his dirty work for him.)

In any case, insurance is only one of the ex-doctor’s vocations. He also volunteers as an unofficial on-call medic at a home for the destitute blind run by the Reverend Dearborn, himself sightless (though hardly destitute). Orloff’s work for Dearborn has to stay below-board because his license to practice medicine was revoked years ago— “brilliant but unstable,” they called him. And on the subject of things Orloff does in an unofficial capacity, he also hints strongly to Stuart that he expects his generosity to be repaid in the form of a modest donation to Dearborn’s charity. Dearborn himself isn’t in when Stuart stops by to do just that, but Orloff is, and the doctor offers to show Stuart around until the boss-man returns. When Orloff leads Stuart into the upstairs chamber that serves as his makeshift clinic, however, Stuart is seized and straight-jacketed by a hulking inmate named Jake (Wilfred Walter). The next we see of Henry Stuart, Lieutenant Holtz and his men are extricating his dead body from the mud just below the river’s high-tide line.

It is at this point in the film that The Human Monster unambiguously reveals itself as a true horror film, and not just a macabre mystery on the same model as later Edgar Wallace adaptations like Chamber of Horrors. Not half an hour in, we already know exactly who the killer is, and we’ve got a pretty good idea why he’s doing it. It comes less as revelation than as confirmation when Holtz eventually discovers that the people listed as beneficiaries on the insurance polices covering the lives of Orloff’s victims don’t really exist, and that the signatures on the documents acknowledging payment were all forged by Grogan, who turns out to know Orloff very well. The question is not “whodunit?” but rather whether Holtz will be able to put the pieces together before Stuart’s daughter, Diana (Greta Gynt, of Bluebeard’s Ten Honeymoons), falls prey to Orloff herself. To what extent this jibes with how Wallace told his version of the story, I don’t pretend to know. I can say only that it helps make The Human Monster an uncharacteristically aggressive picture given the time and place of its origins.

Such a pity, then, that its creators went so far out of their way to sabotage themselves with comic relief shenanigans, courtesy of Lieutenant O’Reilly. I suppose it’s mildly interesting to note that the stereotype of the Ugly American was already securely in place in much its present form as early as 1939; otherwise, O’Reilly contributes nothing but Deep Hurting to The Human Monster. Whether he’s failing to notice the most obvious clue imaginable, pulling out the rubber truncheon he carries on him at all times for the purpose of working over suspects on the slightest provocation, expressing his annoyance at how none of his British counterparts ever get to use their guns, or inappropriately attempting to romance the world’s ugliest policewoman, you can count on O’Reilly to make you cringe just about every time he shows up onscreen. And since he and Lieutenant Holtz spend most of the movie essentially joined at the hip, he shows up onscreen an awful lot. Come to think of it, I wouldn’t be a bit surprised to discover that it was precisely O’Reilly’s antics that sold Monogram Pictures on the idea of distributing The Human Monster in the United States. Certainly nothing else about this movie seems to fit well with the rest of the Monogram horror catalogue. In any case, it’s a terribly annoying business, this comic relief shit, because it comes within an ace of completely ruining what is otherwise a very solid and potentially highly effective film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact