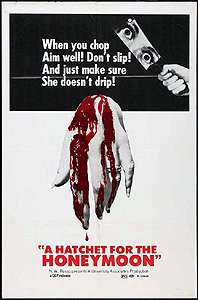

A Hatchet for the Honeymoon / Blood Brides / Il Rosso Segno della Follia (1970/1974) ***½

A Hatchet for the Honeymoon / Blood Brides / Il Rosso Segno della Follia (1970/1974) ***½

It’s remarkable how quickly Mario Bava moved beyond what we now consider the limits of the genre he principally originated. Depending on whether you want to count his not-quite-there-yet Hitchcock pastiche, The Evil Eye, A Hatchet for the Honeymoon was either Bava’s third giallo or his second, yet it shows him already seeking to enlarge significantly upon the formula solidified by Blood and Black Lace. A Hatchet for the Honeymoon is a murder mystery of sorts (any movie trying to qualify as a giallo must at least pretend to be one of those), but the killer himself is the one doing the sleuthing when it comes to the truly unsolved crime— which occurred decades before the film’s main action— and the clues are all hidden in the assassin-turned-detective’s repressed childhood memories. And as if that weren’t unusual enough on its own, A Hatchet for the Honeymoon also finds time to be one of its era’s stranger ghost stories.

I’m going to let John Harrington (Stephen Forsyth) speak for himself by way of introduction: “The fact is that I am completely mad— the realization of which annoyed me at first, but is now amusing to me.” By his own count, Harrington has murdered five women, all of them either brides or at least dressed up as such at the time. He doesn’t kill for pleasure, nor is he motivated by greed, revenge, or even simple misogyny, although each of those things is visible to some degree in his emotional makeup. Rather, he does it because each time he carves up a woman in a bridal gown, he unlocks a new piece of the repressed memory that has tormented him since he was an adolescent: the murder of his own mother on the night of her second marriage. I don’t know how John discovered that reenacting the crime caused him to remember more of what happened that night, but being the psychopathic asshole that he is, he naturally concluded that his need for closure was more important than the lives of however many young women it will take to drag his hidden recollections completely into the light.

The method whereby Harrington selects his victims is impressively audacious. John’s mother was a fashion designer, the head of her own studio, and he inherited the business following her murder. Upon coming of age, John reoriented his mother’s company toward specializing in wedding apparel. Nevermind that he lacks the talent as either a salesman or a designer to keep the firm profitable with such a narrow focus; the important thing is that his models and customers between them provide him with a handy pool of brides and bride-impersonators from which to harvest his mnemonic aids. So far, John has been careful. Inspector Russell (Jesus Puente, of Count Dracula and Perversion Story) has noticed that an acquaintance with Harrington is the sole apparent common factor in the Honeymoon Murders, but no matter how many times he interrogates his favorite suspect, he can uncover no trial-worthy evidence linking John to the crimes (as opposed to just the victims).

Then two things happen that collectively break the stalemate. First, Helen Wood (Dagmar Lassander, from The House by the Cemetery and Black Emanuelle 2) comes to work for Harrington as a model. Then, John breaks with his usual pattern, and kills somebody even closer to home than a client or an employee. Helen is important because John views her differently from the rest of his staff. Most of the time, Harrington can be counted upon to regard his models with that species of veiled misogyny that insecure, inexperienced young women so often mistake for rugged charm. Helen, though— Helen he likes. She’s the first female he’s dealt with in all his adult life whom he can see as more than a key to one of his subconscious mental padlocks, and the fact is that he doesn’t want to kill her if he can at all avoid it. It should be obvious, though, that maintaining a normal social life is a challenge for a pathological killer. All that time John starts spending with Helen also brings us, in a roundabout way, to the second sweeping and destabilizing change in Harrington’s routine. You see, there’s one tiny, trivial obstacle to the romance developing between John and Helen— John is already married. It’s a most unhappy partnership on both sides, however, and would probably never have formed at all were Harrington not in such chronic need of cash to keep his design firm afloat just a few murders longer. Mildred Harrington (Laura Betti, from Twitch of the Death Nerve and The Canterbury Tales) is… well, pretty much every unappealing thing you might expect of somebody named Mildred. A spiteful, surly, belittling, emasculating shrew, she never lets slip an opportunity to humiliate her husband, or to call into question his competence, intelligence, or virility. Not that John is exactly a prize either, of course, even apart from his being a murderer. Arrogant, emotionally stunted, economically parasitic, and impotent to boot, he’s basically the Amazing Colossal Jerk, however attractive he might look from a distance. The natural reaction to seeing the couple in action is to shrug one’s shoulders and say they probably deserve each other. John would not agree with that last part, however. He figures he’s more than done his time in wedlock to Mildred, and he wants out— especially after he starts to get close to Helen. For Mildred, though, the vindictive pleasure of denying John a divorce is the last little scrap of enjoyment that she can extract from the marriage, so she isn’t about to turn him loose.

Inevitably, Mildred’s refusal will get her a date will John’s meat cleaver sooner or later, but A Hatchet for the Honeymoon goes in a very peculiar direction once that deed is done. As hateful in death as she was in life, and with considerably greater justification, Mildred returns as a ghost to haunt her husband, in the most inventively nasty way she can contrive. In an exquisite inversion of the common ghost-story trope, the undead Mildred is visible to everyone but John, whose side she never leaves. Let’s see him try courting Helen or picking up brides to butcher for his intracranial murder investigation now! It isn’t just that being cock-blocked (or cleaver-blocked, for that matter) from beyond the grave is really annoying, either. Given the importance with which Harrington has invested his crimes, it stands to reason that being unable to carry them out in his accustomed manner is going to make him sloppy. And sloppy is the one thing that at serial killer absolutely cannot afford to be.

The first thing about A Hatchet for the Honeymoon that’s likely to jump out at the modern viewer is the resemblance between John Harrington and American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman. I don’t think the connection actually means much, but it’s interesting to see what a satirical character looks like played straight instead. That’s particularly true here, because the central insight behind American Psycho’s satire— that so much of the modern world is set up to reward deeply antisocial behavior— is already unmistakably present in A Hatchet for the Honeymoon. It just isn’t the point of the story here. Like Bateman, Harrington has come to terms with his madness, and has placed himself in a setting that facilitates acting upon its drives. Meanwhile, the widespread human weakness for admiring the totally self-willed has made John a popular man, even to the extent of shielding him from any suspicion save that of one extremely perceptive and dogged cop. Women especially seem defenseless against Harrington’s charms, at least until Mildred’s ghost starts loitering around him all the time. Bava seems to be aware of what he’s touched on with Harrington, too, even if a critique of how we make things easy for intelligent sociopaths falls outside his actual aims for this film. After all, it cost Bava and his crew a lot of hassle to use Francisco Franco’s Barcelona villa for the interiors of the Harrington mansion, so we should probably interpret the shooting location as a nod toward a muted American Psycho-like theme.

Returning now to the subject of pushing past the limits of the giallo so early in the genre’s development, it’s worth noting that the character of Mildred didn’t appear at all in Santiago Moncada’s original screenplay; Bava added her in order to give Laura Betti, whom he’d recently befriended, a part to play. If Moncada had had his way, A Hatchet for the Honeymoon would have had no supernatural angle at all. That would have been a terrible loss, I think, not because I have anything against an unadorned giallo, but because Mildred’s is such a wickedly well-designed haunting. Making her husband miserable was her only pleasure in life at the end, and no way in hell is she going to let a little thing like her death deprive her of it. She could definitely teach a thing or two to all the ghosts who spend eternity hanging about the spots where they died, hoping to scare some random stranger into finding and properly disposing of their bones. Still, even without Mildred, the movie does some really neat stuff to set it apart from the typical spaghetti slasher. I particularly like its fusion of the Lifestyles of the Sick and Twisted subgenre with the more traditional murder mystery. On the one hand, A Hatchet for the Honeymoon skillfully reverses the typical giallo story structure by making the legitimate detective the antagonist, and by having us view the crimes through the perpetrator’s eyes. But then it adds another layer with the motive behind Harrington’s killing spree. Murder in the gialli is usually a simple matter of greed or revenge, and if not that, then it’s something truly irrational, like an outgrowth of psychosexual pathology. But in A Hatchet for the Honeymoon, we have a motive that manages to be both internally logical and utterly deranged. That’s by no means an easy thing to pull off, and even more impressive, the specifics are something I can’t recall ever seeing anywhere else. I can understand why Bava would leave the giallo behind altogether in another two years. By that point, he’d done more with the form in half a dozen films than most of his imitators could accomplish in half a hundred.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact