Revenge in the House of Usher / Neurosis: The Fall of the House of Usher / Neurosis / Nervose (1982?) -*

Revenge in the House of Usher / Neurosis: The Fall of the House of Usher / Neurosis / Nervose (1982?) -*

Jesus Franco worked for Orson Welles for a while. No, really— it’s true! Welles was fundamentally ill-suited to Hollywood, where commerce could be counted upon to trump art every time, and from the end of 1947 until 1970, he spent most of his time in Europe. Over there, he felt freer to make movies that meant something to him, and to make them his own way. Unfortunately for Welles, “his own way” was very expensive, consumed a great deal of time, and involved rather a lot of bridge-burning. His long sojourn abroad produced The Third Man, Mr. Arkadin, and The Trial, but it also produced a problem-plagued version of Othello, a television pilot called Portrait of Gina which Welles himself deemed hopeless after cutting and re-cutting it for six years, and sprawling renditions of Don Quixote and Treasure Island which were never completed at all. Never finishing a movie that you spend millions of dollars to start is a no-no even in Europe, and although it’s standard practice for film productions to take out insurance against exactly that eventuality, you know how insurance is— once you have to use it, good luck ever getting more of the shit! In 1963, when Welles was in Spain trying to get started on his epic Shakespeare fanfic, Chimes at Midnight, he found himself unable to get the insurance he needed to protect the necessary investment. In the end— or so Jesus Franco says— an insurer was found that would write the required policy if and only if Welles could find an assistant director with an impeccable reputation for working fast and cheap, to counteract his own tendency to work slowly, wasting money by the barrelful. In Spain in the early 60’s, few filmmakers worked faster or cheaper than Franco, say whatever else you want to about him. Welles was somewhat familiar with his work, too, having seen and enjoyed Death Whistles the Blues in Paris the year before, and a screening of Rififi in the City (a picture strongly influenced by Welles, fortuitously enough) convinced him that Franco was the man for the job. The two men later had a falling-out that caused Welles to remove Franco’s name from the credits to Chimes at Midnight, but that didn’t affect the admiration that the young Spaniard felt for Welles. Finding them takes more patience than most normal people have with Franco’s films, but if you know where to look, his later work is riddled with Wellesian allusions. And that, believe it or not, brings us to Revenge in the House of Usher.

Perhaps you’ve heard this one before. An aged man, a titan in his field, respected and loathed in roughly equal measure by those who knew him in his prime, lies dying in his decaying palatial home. A former admirer comes to visit, and a cryptic pronouncement from his moribund host launches him on a quest to understand and define the man behind the legend. The conflicting testimony he receives often raises more questions than it answers, until the visitor-turned-detective is forced to consider that maybe people are ultimately impervious to that sort of analysis. It’s Citizen Kane, right? Sure— but it’s also Revenge in the House of Usher. It sounds ridiculous to draw such a comparison, and it’ll seem even more ridiculous if you actually watch this leaden, directionless, half-assed piece of shit, but the broad-strokes plot structure and central psychological themes of the two films are essentially the same. That would probably be even more apparent if we could see Revenge in the House of Usher the way Franco intended, but like A Virgin Among the Living Dead, this movie was too bewilderingly opaque in its initial form to attract any buyers— and unlike the earlier film, this one has yet to find a home video distributor willing to pare away two successive layers of inserts and re-edits to restore Franco’s original vision.

The Kane figure here is Professor Roderick Vladimir Usher (Howard Vernon, from The Blood Rose and Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein). Usher has a bit more life in him yet than his Wellesian counterpart, although he’s conspicuously pretty far gone in physical enfeeblement, insanity, and senile dementia. Who knows how long it’s been since he last left his castle, but he is at least still able to hobble around a bit on his cane— and apparently to oversee the occasional kidnapping and murder. The old doctor has a daughter, you see, and he disagrees with the whole medical establishment of Europe that Melissa (Françoise Blanchard, of Caligula and Messalina and The Living Dead Girl) is dead. That’s why every so often, he sends out his servants, Matthias (Jean Tolzac, from The Erotic Dreams of a Lady and Nathalie: Escape from Hell) and Morpho (Olivier Mathot, of Cannibal Terror and The Sadist of Notre Dame), to collect some girl from the nearest village to serve as Melissa’s latest mad-science blood donor. Usher’s transfusion experiments have yet to produce any result as dramatic as the supposedly-not-dead girl getting up, moving around, or speaking, but they’ve certainly kept her from decomposing, so I guess there must be something in them.

Usher doesn’t remember this, but he recently wrote to an old student of his, Dr. Allan Harker (Antonio Mayans, from Devil Hunter and Golden Temple Amazons), begging him to come out to the castle for reasons he would explain later. (By the way, pay no attention to the English-language dub. The character’s name is Harker— not Hacker— as will become obvious shortly when another character whose name is inexplicably pilfered from Dracula shows up.) What he wanted, of course, was a hand in perfecting his transfusion treatments so that Melissa could at last be fully restored. All Harker sees when he arrives, though, is a loony old man shouting at phantom persecutors and denying that he ever knew any Allan Harker. Luckily, Maria the housekeeper (Lina Romay, of Rolls Royce Baby and Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula in Eight Legs to Love You, remarkably keeping all of her clothes on for once) gets Usher settled down enough to recall who his guest is and why he was summoned. Harker is sufficiently rattled, though, that he’ll think of nothing for the moment but to run into the village to fetch Dr. Seward (Franco’s favorite composer, Daniel White, who can also be seen acting in The Erotic Rites of Frankenstein and Diamonds of Kilimandjaro). Oddly, the doctor doesn’t say much about Usher’s condition during the ensuing house call. Instead, he and the professor mostly discuss long-ago grievances about some work Usher was doing 20 years back, which got him expelled from some academy or other. Yes, that would be whatever he’s doing with Melissa, but Harker hears enough to understand only that he doesn’t understand.

That night, Harker is awakened by the sound of girls sobbing. Following the cries leads him to a cell where three of the village lasses are imprisoned, presumably awaiting their turns in Usher’s lab. They tell him that Usher is a monster, and plead with him to release them, but that would require a key that Harker doesn’t have. Also that night, Harker finds Matthias locked in a different cell, prattling about having done something to displease his master, and seeming blithely unaware that he might have been treated unjustly. Then, right before returning to bed, Harker has a run-in with a bloody-lipped, cadaverous-looking woman whom we will eventually come to know as the ghost of Usher’s wife, Olberta. In the morning, however, the visiting doctor will believe that everything he experienced was part of a bizarre nightmare— which might actually be true, for all the impact the night’s adventure has on the rest of the story.

The following day is dedicated to explanations of a sort. Usher, seeming much more lucid than before, calls Harker in and asks him to take notes as he describes his life’s work. Over the next several hours, the old man explains how Melissa fell gravely ill, how he discovered the secret to keeping her alive in spite of the disease with blood stolen from other girls, and how his activities made him a pariah, hunted by the law all over Europe. The younger doctor doesn’t know what to make of his host’s confession (which would seem to dovetail neatly with that “dream” from last night), or of his claim to have lived for 200 years thanks to the collateral effects of his work preserving Melissa. It sounds impossible, certainly, and Harker has much reason to doubt anything his mentor says in his current condition. For that matter, Seward is frankly of the opinion that Usher’s story should be discounted as the raving of a madman. But as Harker digs deeper, it seems more and more that something strange is going on in that castle, and that it’s only getting weirder and more dangerous as the professor’s deterioration accelerates.

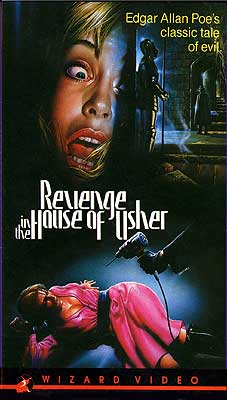

There was apparently only one public screening of what Franco called The Fall of the House of Usher (El Hundimiento de la Casa Usher), at a Spanish film festival where it went over like bacon-wrapped scallops at a Passover Seder. The film did ultimately find three distributors, but only at the cost of extensive alterations— to the point that it makes some sense to treat the different versions as entirely separate entities. For the Spanish commercial release, retitled The Crime of Usher (El Crimen de Usher), a number of gory murder scenes were added, apparently to remove any question in the viewer’s mind over whether Usher was telling the truth about his ghoulish research in his confession to Harker. That version has never been made legitimately available in the United States, although bootlegs do turn up from time to time. In France, Eurocine took a more radical approach. Judging Franco’s preferred cut too short and too boring, they not only ordered new scenes shot (possibly including all the material involving Melissa, Morpho, and Matthias, although I’m by no means sure about that), but also padded out the confession scene with nearly fifteen minutes of footage raided from The Awful Dr. Orlof! Those inserts, consisting of nearly every moment when Howard Vernon was onscreen, plus a few clips of Morpho at work, became a series of flashbacks to Usher’s early years in the mad science business. It was that version— called Nervose at home, and shown in some English-speaking markets as Neurosis or Neurosis: The Fall of the House of Usher— that Charles Band picked up for US distribution through his Wizard Video label, changing the title once again to Revenge in the House of Usher. The Wizard Video cover art rather mysteriously featured the image of a woman being threatened with a power drill, something which not only never happens in the Eurocine cut of the film, but would seem flatly incompatible with its vaguely old-timey setting. I suppose it might be a misplaced reference to one of the Crime of Usher murder scenes, however.

Along with the difficulty of deciding how many movies we’re properly talking about, it’s also a challenge to figure out when exactly Revenge in the House of Usher (or whatever you want to call it) was made. The 1988 release date given by Netflix Instant, the Internet Movie Database, and various other online resources is plainly incorrect. Wizard Video issued their edition in 1985, so Revenge in the House of Usher must be at least that old. Other sources claim 1982 or 1983, although many of them simultaneously give reason to doubt their accuracy. When The Sleaze Merchants, for instance, mentions this movie in passing in the chapter on Franco, the description strongly suggests that author John McCarty had not actually seen it when he was writing, and was relying on some other source which either he misunderstood or which gave him plain old bad information. I’m going with ‘82 for now, on the grounds that it seems to be attested slightly more often than ‘83, but again I don’t really know. As for that 1988 business, I think it’s a case of mistaken identity. In some markets, for some unfathomable reason, Revenge in the House of Usher circulated under the title Zombie 5. Zombie 5 is also the equally indefensible American-release title of Raptors: Killing Birds, which really was made in ‘88. It would be a simple matter, or so it seems to me, for wires to get crossed somewhere, so that that Zombie 5’s release date started being erroneously attributed to this Zombie 5.

If you get the impression that I’m stalling here, trying to put off having to subject Revenge in the House of Usher to direct analysis, well… I kind of am. When you watch as much Franco as I have now, you learn to recognize when you’re in the presence of a movie that held some personal meaning for him. However, Franco’s most personal work is characterized by a remarkable nonchalance about whether or not the viewer can extract that meaning, or indeed get anything out of the picture at all. I try to do all I can to be fair to such films, but in this case, I’m not even sure what that would mean. With Revenge in the House of Usher, I have no background information like the Soledad Miranda-Virgin Among the Living Dead connection to serve as a Rosetta Stone, and it isn’t for lack of searching. I have no idea why Franco chose to mash up “The Fall of the House of Usher” with Citizen Kane, and to populate the resulting story with characters borrowed from Dracula, so there’s no way for me to tell whether this movie is succeeding in some secret business of importance only to its creator. And of course, it doesn’t help that the version I watched wasn’t truly Franco’s anyway. The Eurocine cut is all I’ve got to work with, though, so here goes…

The overwhelming impression left by Revenge in the House of Usher is one of directionless time-killing. The Eurocine cut is the kind of movie a person would make to get out of a contract with arch-philistine producers who cared only that they received x minutes of footage adding up to something that technically qualified as a narrative. Except during the intrusive Awful Dr. Orlof clip-show, we could almost be watching somebody’s home movies, so banal is most of the action. Usher, Maria, and the other servants go about their daily routines. Harker strolls around the castle, inquiring into this and that as if no more were at stake than a small bank loan or Usher’s eligibility for a grant to cover live-in nursing care. Guests like Dr. Seward come and go, making no real impact on anything. The late Mrs. Usher and a handful of other ghosts do eventually rise up to carry away Roderick with them to the other side, precipitating the expected collapse of the house (which naturally happens mostly off camera), but we’re never allowed to know those spirits well enough to tie their actions to anything we’ve seen up to then, so the conclusion feels disconnected and arbitrary. Horror content (disregarding, again, that borrowed from The Awful Dr. Orlof) is limited to Harker’s weird first night in the castle, a couple of listless forced blood transfusions, and Mrs. Usher’s ghost girls playing Ring Around the Rosie to intimidate various living characters. Astonishingly for a Franco movie, there’s no eroticism at all— not even a salacious nightclub routine! All in all, Revenge in the House of Usher as it has come down to us from Eurocine via Wizard Video has almost literally nothing to offer beyond the intriguing mystery of why a movie so seemingly pointless exists in the first place. Given its status as a stealth tribute to Citizen Kane, I suppose it’s perversely appropriate that Revenge in the House of Usher should be its own Rosebud.

In celebration of getting our home-base website more or less rebuilt after a catastrophic server failure, we B-Masters have hastily slapped together a roundtable devoted to movies about other returns from the dead. Click the banner below to see what else has clambered out of the grave:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact