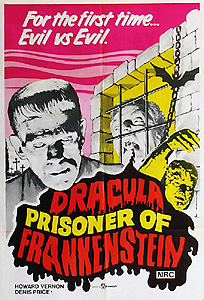

Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein / Dracula vs. Frankenstein / The Screaming Dead / Dracula Contra Frankenstein (1972) -**Ĺ

Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein / Dracula vs. Frankenstein / The Screaming Dead / Dracula Contra Frankenstein (1972) -**Ĺ

It takes an extraordinary filmmaker to turn a project as banal as an update of Universalís mid-40ís monster rallies into something memorably baffling and bizarre. I suppose I shouldnít be surprised that Jesus Franco was among those who pulled it off. His Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein isÖ well, frankly Iím really not sure what it is. My fellow B-Master, Will Braineater, suggests that Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein might be a diligently deadpan spoof of 1940ís horror movies, or perhaps a sidelong comment on the increasingly obvious irrelevancy of efforts by outfits like Hammer Film Productions to go on working that mined-out vein 30 years later. Iím not convinced, at least insofar as weíre talking about Francoís conscious intentions, but this movie surely does function that way as a practical matter. Whatever its true object, Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein draws the maximum possible attention to how pointlessly ritualistic Universal-inspired horror films had become by the early 1970ís, by being more ritualistic and pointless than even the worst of them. Its main villainís scheme serves no apparent purpose; its secondary villains are allowed no independent agency; its tertiary villainsí objectives, loyalties, and very existence are never examined or explained; and its hero accomplishes absolutely nothing through his own actions after the close of the first reel. In the end, I could not be sure that what Iíd just seen even qualified fully as a movie.

Count Dracula (Howard Vernon, from The Bloody Judge and The Sadistic Baron Von Klaus) is a real pain in the ass. From his hilltop castle overlooking some little Romanian village, he terrorizes the populace with impunity, slaughtering the young and blighting the lives of their elders with grief. The villagers themselves lack the courage, the will, or the knowledge to stop him, and even the local Gypsy tribe seems powerless to do anything about the vampireís depredations despite being led by a genuine, no-fucking-around witch (Genevieve Deloir, of Devilís Island Lovers). Fortunately there is one person who is not cowed by the undead menace, English physician Dr. Jonathan Seward (Alberto Dalbes, from Maniac Mansion and The Demons). Seward has had his fill of being called to the homes of grieving townspeople to drive nails through the eyes of their bloodless daughters as prophylaxis against evil resurrection (clearly Franco has seen Black Sunday), and he now takes it upon himself to rid the village of its pestilence. Harnessing his horses to a carriage thatís going to become very confusing when modern appurtenances like cars and flashlights begin turning up a couple scenes later, he drives to Castle Dracula in grim and silent determination. It is midday when Seward enders the castle vault, and he catches Dracula lying lifeless and helpless in his coffin. The effect of the stake Seward drives through the vampireís heart is rather different from what 40 yearsí worth of movies, 150 yearsí worth of literature, and untold centuriesí worth of oral tradition have conditioned us to expect, however. The cardiac transfixion is indeed fatal, but instead of skeletonizing, crumbling to dust, or just plain dying, the slain Dracula transforms into a dead bat. The stake, meanwhile, shrinks to a fraction of its original size, and somehow migrates from the vampireís heart to the batís anus. Really.

Itís rather too early in the film for a happily-ever-after, though, and some time later, two more foreigners arrive in town driving the single weirdest hearse I have ever seen. Subsequent scenes will have them tooling around in a more or less conventional Mercedes, but this thing looks like some automotive Frankenstein tried to build a cab-over-engine van on top of a 1958 Plymouth. Thatís only appropriate, really, for the owner of the vehicle is a literal Frankensteinó Dr. Rainier Frankenstein (Dennis Price, from A Place of Oneís Own and Twins of Evil), to be exact. His chauffeur, meanwhile, is yet another incarnation of Francoís ubiquitous mad genius sidekick, Morpho Launer (Luis Barboo, of Conan the Barbarian and The Witchesí Mountain). Luckily for his employer, this Morpho is merely muteó Iíd like to think that a blind man would find it difficult to get a driverís license, even in Romania. The reason Frankenstein has come to this Godforsaken corner of the Carpathians is that he thinks Castle Dracula will afford him just the environment he needs to complete his work.

The extreme paucity of dialogue in this movie (eight lines in the first 40 minutes, and none at all in the first 16Ĺó trust me, I counted!) makes it difficult to be certain, but I think that at this stage, Frankenstein aims strictly at the old family tradition of monster-making. At the very least, Rainier does have a monster (Fernando Bilbao, from Orgy of the Vampires and Hundra) along with him, and his first act upon getting his new laboratory up and running is to activate it via the usual electrical machinery. But soon enough, the mad scientist stumbles upon Draculaís coffin in the basement, discovers the impaled bat inside it, and gets it into his head to try restoring the count to unlife.

And then, because this is a Jesus Franco movie, itís time for a nightclub scene. This is a sad one indeed, too, with a lone singer/dancer (Josyanne Gibert, from I Am a Call Girl and Confessions of the Sex Slaves) performing a lethargic approximation of a can-can routine and belting out what the five words or so of French that I understand suggest to be a song about her buttó which, to be fair, is truly a butt worth singing about. Once the show is over, she retreats to the dressing room to change out of her costume, but she is interrupted after surprisingly little disrobing by Frankensteinís monster. Inevitably, it seizes the girl and carries her off, paying no heed to the efforts of cops or customers to detain it. Iím tempted to ask at this point why nobody thinks to follow the clumsy and slow-moving creature so as to ascertain the location of its lair, but I guess I already know the answer. Itís a monster in a Transylvanian villageó where the hell else could it be staying except at Castle Dracula?

Obviously Frankenstein wants the singer so that he can drain her blood to revive Count Dracula. The revivification goes in directions that are far from obvious, however. Like I wasnít expecting Ranier to pull the stake out of the batís ass, put the bat in a bell jar, and hook both that and the singer up to some sort of Exsanguinomatic, so that the blood drizzles onto the dead bat from above. Nor was I expecting the blood to keep pouring into the jar until the now living and visibly terrified animal was practically swimming in the stuff! And I certainly wasnít expecting a panicked bat in a bell jar to transform via a cheesy stop-substitution effect into a catatonic Howard Vernon, with no more jar to be seen anywhere. Ladies and gentlemen: mad science the Jesus Franco way! In any case, Frankenstein must have outfitted his Resurrectron with an auxiliary Enzombulator, because the vampire will spend the whole rest of the film in that catatonic state, complying with Frankensteinís instructions, but exhibiting no will or intelligence of his own whatsoever. Those instructions concern the scientistís next project, which is to raise an invincible army of vampires; itís a ďrule the worldĒ kind of thing, apparently.

Now if Frankenstein wants to conquer the globe with a legion of the undead, itís a tad inconvenient that heís beginning not merely in the middle of fucking nowhere, but also in the home of the guy who personally defeated Dracula not all that long ago. Rainier does at least realize that, and the first person on whom he sics the count is the madwoman (Paca Gabaldon, of Cannibal Man and Patricia) Dr. Seward currently has confined to his attic for treatment. I guess he figures her for the one person Seward wonít be able to bring himself to stake or to eye-nail, and if so, heís right about that. Meanwhile, Frankenstein also sends his monster after Seward directly, and although the none-too-competent creature fails to kill its target, Seward is sufficiently incapacitated as to be no longer worth worrying aboutó at least until Amira and her Gypsies get hold of him and nurse him back to health. Frankenstein takes steps against that threat, too, singling out the witch for vampire attack, but there are two things he hasnít entered into his calculations. First, although Dracula and Sewardís madwoman may be securely under his power, thereís a third, free-range vampire (Brit Nichols, from A Virgin Among the Living Dead and The Erotic Rites of Frankenstein) dwelling in Castle Dracula, whose coffin in the laundry room (to judge from the blatantly obvious direct current outlet in the wall directly above) Frankenstein has unaccountably failed to discover, despite its placement completely out in the open not twenty feet away from where the other two vampires sleep through the day. And secondly, Amiraís contacts in the spirit world inform her that a werewolf (an actor identified only as ďBrandy,Ē who seems not to have appeared in anything else ever) is on his way to the village, due to arrive in time for the next full moon. Frankensteinís scheme will surely not survive the ensuing monster free-for-all, so Seward and the villagers wonít need to lift a torch or a pitchfork to regain control of their townó not that thatíll stop Seward from putting together the requisite mob anyway, or from offering God a prayer of thanksgiving for granting him victory when he and the peasant posse arrive at the castle too late to do anything but to box up the bodies and to put out the electrical fire in the lab.

I canít believe I just spent over two pages describing the action of a movie in which next to nothing actually happens. Iím glad I did, though, because Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein is one of those deceptive films in which you recognize only in retrospect how insubstantial it really is. The whole while, it seems like stuff is happening (albeit very slowly), or is at least about to happen, but looking back from the closing credits, you realize that Frankenstein managed to recruit but one lousy vampire to his ďarmy.Ē You realize that Dracula spent so much of the movie sleeping that he made Mothra look positively hyperactive. You realize that the climax to the fight between the wolf man and Frankensteinís monster happened off-camera. You realize that you donít have the first goddamned clue who the werewolf and the blonde vampire girl in the laundry room were, where they came from, or what they wanted. And you realize that neither Dr. Seward nor Amiraís Gypsies ever contributed shit to the baddiesí final defeat. Itís like a dream that seems to tell a logical and coherent story while youíre in the midst of it, but appears utterly nonsensical under the scrutiny of the waking mind. Franco did that sort of thing a lot in the early 70ís, of course, but to see the narrative sensibility of A Virgin Among the Living Dead applied to the old House of Frankenstein template somehow feels so counterintuitive that Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein acquires a fascination that it definitely doesnít deserve on the basis of its actual effectiveness, which is close to nil in all departments.

The werewolf and the Frankenstein monster, to begin with, look ridiculous. Both makeup designs closely follow those devised by Jack Pierce for Frankenstein and The Wolf Man, but the makeup artists here are no Jack Pierce. The results of their labors recall Kiss Me Quick and Orgy of the Dead more strongly than Universal, as if they were good Halloween costumes instead of professional monster makeup. It also doesnít help one bit that Fernando Bilbao apparently modeled his performance after Bela Lugosiís in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, all blind stumbling and waving arms. The monsterís creator, meanwhile, is rendered absurd by casting alone. Although Dennis Price had once been a justly respected actor, he was a bloated and raddled drunk by 1972, and Franco apparently didnít trust him to deliver any dialogue. Whenever we hear Frankenstein, it is merely his internal monologue in voiceover, speaking aloud his musings over his laboratory notes or composing the dayís journal entry. As evil geniuses go, he rates a bit behind your most embarrassing uncle or your mother-in-lawís repellant new boyfriend. Dracula has a different problem. Honestly, I get the impression that Howard Vernon would have made a terrific Dracula in a movie that permitted him to do more than to glare fixedly straight ahead, with his lips curled back in a motionless snarl. Iíve seen Vernon be both debonair and menacing in other films (most notably The Awful Dr. Orlof), and I applaud the frequency with which Franco cast him either as a villain or as a character whom weíre meant to suspect of being a villain. However, Draculaís role in this story is such that Vernonís abilities are thoroughly wasted, and to watch him in action here is to be teased constantly with visions of another, better film. Much the same can be said of Brit Nichols as the inscrutable vampire girl. She has the ďseductive power of evilĒ thing nailed, but sheís so divorced from the rest of the action that she might as well have been spliced in by mistake from some other movie.

The greatest weakness of Dracula, Prisoner of Frankenstein, though, has to do with the allocation of storytelling resources, and can best be illustrated by a comparison between how it treats Jonathan Seward and how it treats the girl from the nightclub. Seward, remember, is the nominal hero of this picture. Yet heís a complete non-entity, receiving hardly any screen time when heís neither driving his buggy to or from the castle nor being spied on from a distance by Frankenstein or one of his agents. We donít know him, we donít understand what heís doing here in Transylvania, and apart from the fact that heís named after two of Bram Stokerís good guys, thereís no clear reason for him to be such a big deal in the vampire-fighting business that Frankenstein knows him by reputation already when he arrives in the village. The nightclub singer, on the other hand, serves no function but to become Draculaís unwilling blood donor, yet we get a better sense of her as a person than we do any of the other characters. We donít ever learn her name, mind you, but from seeing her act in its entirety and observing the contrast between her lascivious stage persona and her more matter-of-fact demeanor when interacting with her coworkers out of public view, enough of an impression emerges that I expected and indeed wanted to see more of her. This happens throughout the movieó things that donít matter get all the attention, while the ostensibly important stuff gets sort of vaguely indicated, and then largely ignored. If you havenít yet succumbed to the Franco virus, you can safely skip this one. We who have succumbed will agree that youíre probably better off, even as we sit down to watch it yet againÖ

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact