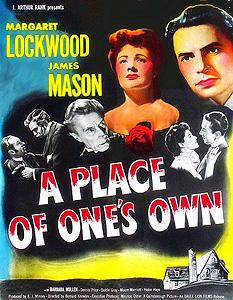

A Place of One’s Own (1945/1949) **

A Place of One’s Own (1945/1949) **

It would be possible to write a fairly substantial book delineating the differences in approach and subject matter between British and American horror movies during the 30’s and 40’s, but there was at least one major respect in which the two industries tracked each other very closely. In Britain just as much as the United States, filmmakers in those days seemed virtually incapable of taking ghosts seriously. The shades of the departed were relegated almost exclusively to silly comedies, and more often than not, they’d stand revealed in the end as an elaborate cover story for thieves or smugglers or Nazi sympathizers. About the best thing a spook could hope for was to figure in some schmaltzy melodrama on the model that would eventually produce Ghost; there, a phantom might at least maintain a little dignity, even if he or she would still be about as terrifying as Casper. It’s a curious phenomenon either way, but doubly so in the British case. After all, the Isles have one of the proudest ghost story traditions in Europe, encompassing everything from local legends to internationally respected works of literature like The Turn of the Screw and A Christmas Carol. That paucity of serious 30’s and 40’s ghost movies is what gives A Place of One’s Own its main point of distinction. Like Hollywood’s contemporary The Uninvited (which A Place of One’s Own closely resembles), it defies the accepted practice of its era by serving up a haunting that means it.

Bellingham House, in the little town of Newborough, has lain vacant for 40 years, ever since the death of its last owner, Elizabeth Harkness. Miss Harkness had been an invalid, and the official verdict at the coroner’s inquest was that she died of a medication overdose— although the question of whether it was accident or suicide was never really resolved. And because the dead girl’s will left all the money and property in the hands of the servants, Mr. and Mrs. Abbott, the Newborough rumor mill has it that Elizabeth was likely as not murdered for the inheritance. If so, it didn’t do the Abbotts a lot of good, since they were not among the survivors when their ship to the New World went down shortly thereafter. That all happened in 1860 or thereabouts. Now, in the spring of 1900, Bellingham House has finally found new occupants in the form of Henry and Emilie Smedhurst (James Mason, from 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and The Night Has Eyes, and Barbara Mullen). Brighouse the estate agent (Clarence Wright) gives them an impossibly good deal on the property, but Henry is too hard-headed a businessman to care much about why once he ascertains that the house and its grounds are in good condition, all things considered.

Emilie, however, is not remotely hard-headed, and she suspects at once that there’s something peculiar about the Smedhursts’ new house. It’s nothing concrete, you understand— just a vague impression that the building is somehow permeated with the essence of its previous owners. She isn’t the only one who gets that vibe from Bellingham House, either. When the Smedhursts embark on their new small-town social life by inviting Major Alistair Manning-Tutthorn (Michael Shepley, from The Triumph of Sherlock Holmes) and his family over for dinner, Florence Manning-Tutthorn (The Frightened Lady’s Helen Haye) fills her hosts in on the real reason why it took four decades and some newcomers from Leeds to turn the old Harkness mansion back into a functioning domicile. Most of Newborough considers Bellingham House haunted, presumably by the spirit of Miss Elizabeth, and lots of folks wouldn’t set foot in the place if you paid them. Henry scoffs at the notion (with that amazing mannerly rudeness that no one has ever been able to do quite like James Mason), and declares that he’s outright pleased with his home’s sinister reputation— he’d have paid easily twice as much for the place without it. At that point, the focus of both the conversation and the movie shifts to Annette Allenby (Margaret Lockwood), Mrs. Smedhurst’s hired companion (believe it or not, well-to-do British ladies used to pay girls to pretend to be their friends— I’m really not sure what to make of that), and Dr. Robert Selbie (Dennis Price, of The Earth Dies Screaming and Venus in Furs), the nephew of the Manning-Tutthorns. The relative youngsters seem to have hit it off most successfully, to the degree that they’ve both got “LOVE INTEREST” written all over them.

As in most halfway-competent haunted house movies, the supernatural inhabitant of Bellingham House makes its presence felt very gradually. After Emilie’s ill-defined weird feeling, the first manifestation is a call on the voice tube (a sort of primitive intercom system that is literally what the name implies) that comes through to the room where the Smedhursts habitually eat their breakfast at a time when there should be no one else in the house to initiate it. Henry answers the mysterious call, but he can hear no one on the other end, and he eventually becomes so flustered that Emilie takes the tube away from him. When she does, she hears the faint, female voice whispering, “Send for Dr. Marsham.” Then there’s an odd incident involving George the groundskeeper (Moore Marriott, from The Sign of Four and the 1928 version of Sweeny Todd), who swears that he heard a woman’s voice ordering him to dig up the fallow patch in the garden as he was retiring to his room one night. Emilie, Annette, and Sarah the maid (Dulcie Gray) alike all deny issuing such instructions. And while George digs, he uncovers a gold locket buried in the topsoil, which Sarah presents to Henry to see if it’s anything he recognizes. It isn’t, and what’s more, the locket seems to clean itself of its coating of humus as soon as Henry sets it aside with the intention of doing that job himself later on.

Now that’s all pretty weird, but none of it is exactly what I’d call scary. The scary stuff (or at least the stuff that would be scary if you had to live with it) comes a bit later, when Annette begins acting sort of, well, unlike herself. She plays songs that she doesn’t know on the piano while entertaining Dr. Selbie. She has episodes somewhere between sleepwalking and hypnotic trances, during which she says things that make a disturbing kind of half-sense— things, that is, that have no apparent connection to Annette’s life, but that possess a certain internal logic nonetheless. In particular, she keeps mentioning somebody named Dr. Marsham. In time, it reaches the point where Annette no longer acts like her old self at all, and if any among us were having trouble figuring out whom she’s acting like instead, the decisive tip-off arrives when Annette takes to her bed with some manner of psychosomatic wasting sickness. Dr. Selbie, who understandably takes a rather personal interest in treating Annette, can find nothing physically wrong with her, and despite his endlessly reasserted disbelief in ghosts, Smedhurst comes increasingly to believe that the secret to the girl’s recovery lies in figuring out what really happened to Elizabeth Harkness all those years ago.

I would really like to be able to speak more highly of A Place of One’s Own. To begin with, it is, as I’ve already stated, a very unusual movie for its time, and one naturally wants rare things to be good as well. Hell, A Place of One’s Own is unusual even outside of its time, for it is a possession story as much as a haunted house tale, a distant precursor to Shock as well as a British riposte to The Uninvited. Also, James Mason really brings it in this movie. Mason was younger in 1945 than I am now, but he’s completely convincing as a crusty retired salesman, except when the camera closes in on his undisguisedly wrinkle-free face. (His age makeup is limited to a salt-and-pepper wig and some white paste-on facial hair.) If there had been a British Film Institute award for Best Performance by an Obviously Miscast Actor, Mason would have taken it in a walk. Unfortunately, though, A Place of One’s Own lets down both its premise and its star by being rather dull and unengaging. Possession-induced, psychosomatic tuberculosis is a fairly diffuse threat, and at no point is the pretense that Margaret Lockwood is deathly ill at all persuasive. Annette is pretty listless to start with, and all that perfectly applied blush, lipstick, and eye shadow doesn’t exactly scream, “I’m too sick to leave my bed, and I’ve been this way for weeks.” Furthermore, Lockwood seems not to have grasped the point that she’s supposed to be playing, in effect, a double role. We ought to be able to tell the difference between Annette Allenby and Elizabeth Harkness by something more than a glazed stare and the occasional line of cryptic dialogue. With the main thrust of the plot languishing far more convincingly than the supposedly moribund heroine, A Place of One’s Own comes by its most entertaining moment via pure accident. When the enigmatic Dr. Marsham (not so you’d notice, but that’s Ernest Thesiger, from Bride of Frankenstein and The Man in the White Suit) appears in person at last, the tactics used to set up a twist ending out of our sight lead more immediately to the surely unintended implication that the doctor’s brilliant plan for exorcising the dead girl’s spirit was to give her the consummation to their relationship that she was denied in life! For a moment there, it looks like A Place of One’s Own is about to follow the old Monogram Pictures pattern of creating astonishing perversity through inattention to detail. Frankly, it’s kind of disappointing when the movie rights itself at the last minute.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact