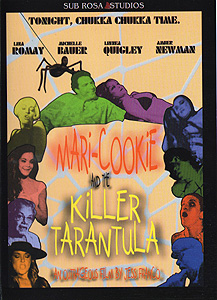

Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula in Eight Legs to Love You / Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula / Eight Legs to Love You / Mari-Cookie y la Tarantula Asesina (1998/2000) -**

Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula in Eight Legs to Love You / Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula / Eight Legs to Love You / Mari-Cookie y la Tarantula Asesina (1998/2000) -**

I want you all to understand that I literally asked for this. I was sitting at a gas station outside of Pittsburgh with my friend, Osco Sean, talking about the sad late-period works of various big-time exploitation movie directors, and I brought up Jesus Francoís Killer Barbys. Sean then asked me if Iíd seen Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula in Eight Legs to Love You, which I had not. That set him off on a lengthy and detailed description of what he swore had to be the worst piece of shit that Franco had ever made, andÖ well, you know how that goes. I may be an unapologetic Franco fan these days, but my God has that man been responsible for some crap! So when Sean talked Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula up as Francoís worst, there was no other way for the conversation to end. I was just going to have to see thing, and the next thing I knew, I was making arrangements to borrow Seanís DVD. Now here we are. After watching Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula for myself, I canít quite agree with Seanís assessment of itó but thatís mainly because this movie is so fucked up and strange as to be essentially beyond measurement. It surely is awful, and it surely must stand as one of the landmarks defining the crummy side of Francoís career, but itís also so utterly, hypnotically wrong in every possible way that Iíd much rather watch it than, say, Kiss Me, Monster just about any time.

In the ďcredit where credit is dueĒ column, Eight Legs to Love You begins with something Iíve absolutely never seen anywhere else. Mind you, I was in no great hurry to see it here, either, but I canít deny the uniqueness of a rape scene shot from a perspective looking out through the victimís vagina. Whatís more, the unconventional angle is even sort of thematically appropriate in a sick way, because the whole purpose of the opening scene is to explain the conception of the title character. During one of Spainís wars with the Dutch Republic, a Dutch noblewoman was raped by a Spanish soldier. Afterward, as the woman lay exhausted on the ground, a spider came along and crawled between her open legs to lay its eggs inside her. The countess conceived as a result of the rape, but we may surmise that it wasnít one of her ova that the Spaniardís sperm fertilized. The child who was born not nearly long enough later was an immortal were-spider! Iím not sure what the countess named her peculiar infant, but in the centuries that have passed since the spider-child grew to maturity, the world has come to know her as Tarantula (Lina Romay, from Killer Barbys vs. Dracula and Jack the Ripper).

Now it used to be that a noble title was the next best thing to an Always Get Away With Anything license, but thatís not as true anymore in the late 20th century. Consequently, Tarantula now finds it expedient to lead a double double life, posing by day as prudish and boring Spanish housewife Mari-Cookie, and sneaking off to her semi-ruined castle only after her oblivious husband, Martin (Robert King, of Biohazard and The Brain), falls asleep. By night, she works as an exotic dancer and prostitute, a profession that affords her a perfectly plausible alibi for going home with a different stranger every eveningó and if those strangers are never seen again, well, maybe they just decided that a wild life of vice wasnít for them after all, you know?

If Tarantula would limit her depredations to lowlife nonentities like lesbian skinhead Leona Tarantino (Mavi Tienda, from Broken Dolls and They Stole Hitlerís Dick), she could probably keep avoiding capture and punishment for another 400 years. Tarantulaís problem is that she has champagne tastes, and canít resist leading the occasional fat cat to their doom, too. When, for example, a well-known musician like Chuck Morrison (assistant director Pedro Temboury ,who can also be seen in front of the camera in Vampire Blues and Lust for Frankenstein) goes missing, people tend to noticeó and they might notice that he used to date Tarantula, too. One person who certainly has noticed is Sheriff Marga (Michelle Bauer, of Reform School Girls and Bikini Drive-In), who (improbable as this may seem for a woman who habitually goes about in public wearing only a g-string, a vest, and an array of gunslinger accessories) is apparently the law in these parts. Marga is also the one person who suspects a connection between Tarantula and Mari-Cookie, to whom she pays a shakedown visit while the latter woman is relaxing by the pool with her friend, Tere (Linnea Quigley, from The Black Room and The Monster Man), and Tereís teenaged daughter, Amy (Amber Newman, of Tender Flesh and Dungeon of Desire).

Unsurprisingly, Marga gets no confession out of Mari-Cookie that afternoon. She has somewhat better luck at the local strip club, though, when she has a chat with Tarantulaís foremost professional rival, Queen Vicious (Analia Ivars, from Dr. Wongís Virtual Hell and Revenge in the House of Usher). Not that Queen Vicious actually has any information to give the sheriff, but sheís more than happy to do anything within her power to bring Tarantula down. Now it happens that Queen Vicious has become sort of a mentor to Amy (for values of ďmentorshipĒ that include offering pro-tips on the finer points of anal sex), and Marga knows that Amy is very much the sort of girl that Tarantula favors. Marga gives Queen Vicious a radio transmitter disguised as a brooch, with instructions to pass it along to Amy. Amy will then go to the club where Tarantula dances, and come on to her. If Marga is right about Tarantula, sheíll take Amy back to her lair, and the transmitter will lead Marga right along behind. Thereís one thing Marga hasnít counted on, though. Tarantulaís powers of seduction are more than natural, so that even her most implacable enemies may be unable to resist her.

As frequently happens with Franco films, synopsizing Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula requires first imposing upon it the structure and order that its creators were content to leave out. For a more accurate impression of the experience of watching this movie, randomly select items from the following list, and insert them between each pair of sentences above:

(a) Tarantula performs a nude dance. (b) Tarantula fucks one of her victims. (c) Tarantula performs a nude dance in slow motion. (d) Mari-Cookie fucks Martin. (e) Queen Vicious performs a nude dance. (f) Tarantula fucks one of her victims while performing a nude dance. |

Overall plot-to-nude-dance-and-fucking ratio? Something like 40-60, although to be fair, there are a few sequences that pull double duty. For instance, Queen Vicious is on shift when Sheriff Marga comes around to interview her, with the result that much of their conversation unfolds with Vicious up on the bar in ass-up/face-down position. Note that this presents Michelle Bauer with the sort of acting challenge that the players in normal movies simply donít have to worry about. I mean, when did Jodie Foster ever have to keep a straight face while discussing serious business with Toni Colletteís nether orifices?

Actresses in the latter league are also rarely asked to pretend to be frightened of spider puppets like the one representing Tarantula in her arachnid form. Itís almost worth watching Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula once just to see this thing. You remember Return of the Fly, with all its ridiculous shots of Brett Halseyís face superimposed onto that embarrassing, immobile model housefly? Well, itís pretty much the same story here, only with Lina Romayís face superimposed onto an embarrassing, semi-mobile model spider. For shots that call for the crude little marionette to be seen moving, it has a dollís head that resembles Romay to roughly the same extent that the puppet version of Dr. Smegma resembled Robert Kerman at the end of Gums. Inevitably, thereís never a transformation scene as such. How could there be in a movie so impoverished that its creators would deem the spider puppet acceptable in the first place? Instead, Tarantula just wanders out of the frame whenever the time comes to shift shapes, and the pathetic rubber bug swings into view to take her place. Incredibly enough, the puppeteer usually canít be bothered to bring the spider in from the correct quadrant of the frame-edge, either!

Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantulaís main draw, though, is probably its appeal to a very specific form of morbid curiosity. Above all, this movie represents an almost unparalleled gathering of over-the-hill scream queens, banding together for the most openly pornographic project that most of them had worked on in many a year. Now I realize that as a libertine lefty, Iím required to believe that all women are beautiful, regardless of size, shape, age, or state of physical repair, but with Eight Legs to Love You, Jesus Franco has found the point where my sociopolitical ideals and my esthetic sensibilities have no choice but to part company. Michelle Bauer and Linnea Quigley are still shapely, handsome women, but both look like theyíve been ridden hard and put away wet a few times too many since the late 1980ís. Analia Ivars is rougher-looking yet, a burly, butch trucker-mama type who might not have been much to look at even fifteen or twenty years ago. The truly shocking thing, though, is what time has done to Lina Romay. I can think of few starker dramatizations of the ravages of age than to watch Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula immediately after, say, Greta the Mad Butcher. Romay is as game and shameless as ever, and the intangible qualities that always separated her from the likes of Bauer or Shannon Tweed remain intact, but even so, I couldnít help wondering from time to time if it would kill her to put some goddamned pants on. It was a novel experience having that kind of reaction to Romay, let me tell you!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact