London After Midnight (1927ó 2002 still reconstruction) [unratable]

London After Midnight (1927ó 2002 still reconstruction) [unratable]

Allow me to draw your attention to the absence of my customary star rating in the line above. This is not because Iíve forgotten somethingó no, Iíve got a very good reason for doing it this way. You see, the version of London After Midnight that I saw isnít really a movie at all, and for that reason, it didnít seem fair to try to evaluate it according to the same criteria I would ordinarily use. I wanted to give it some kind of review, though, because it was a movie once upon a time. Permit me to explain...

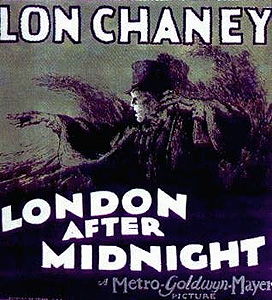

As you may recall me mentioning in passing in previous reviews, London After Midnight is a lost filmó so lost, in fact, that not a single second of footage, either print or negative, is known to exist today. The last extant print was destroyed when the MGM warehouse where it was being stored burned down in the 1960ís. Now that raises the obvious question of how in the hell I managed to see it; after all, I switched majors long before I could get my degree in mad science, so itís not like I built myself a time machine or something. Whatís going on here is that, though no actual film survives, London After Midnight didnít vanish completely without a trace. There are still a few copies of the script floating around, along with some 200 production stillsó photos taken during filming, primarily for publicity purposes. A team of film scholars led by Rick Schmidlin has spent the past several years using those limited resources to attempt a reconstruction of London After Midnight, allowing modern audiences to see at least an approximation of this vanished movie. The result is a bit disorienting at first, but on the whole, Iíd say the project proved remarkably successful.

We begin with the death by gunshot of a wealthy Englishman named Richard Balfour. Scotland Yard detective Edward Burke (Lon Chaney Sr.) is on the scene, grilling the witnesses for information. Balfourís next-door neighbor, Sir James Hamlin (Henry B. Walthall, from The Devil Doll and the 1915 version of The Raven), and Hamlinís butler, Williams (The Unholy Threeís Percy Williams), heard the shot, but both men claim to know nothing more. Balfourís daughter, Lucille (Marceline Day), and Hamlinís nephew, Arthur Hibbs (Conrad Nagel, of One Million B.C. and The Thirteenth Chair), are no help, either. After what seems an awfully perfunctory investigation, Burke decides to take the terse suicide note he found on the dead manís desk at face value, and declares that Balfour died by his own hand.

Five years go by. The Balfour mansion has fallen into ruin after half a decade of abandonment, and Lucille now lives with Sir James. Then one night, Hamlin receives an unexplained visit from a scholar named Professor Edward C. Burkeó obviously, this is really the detective of the same name who handled the Balfour case all those years ago, though his absurdly feeble disguise (consisting of a dye job, a pair of glasses, and a cane) evidently fools all the other characters. Stranger still, at around one in the morning, the Balfour place fills with an eerily intense light, and Williams and the Hamlin maid, Miss Smithson (Polly Moran, of The Unholy Night), catch sight of two threatening and mysterious people prowling the grounds. One of these is a girl (Edna Tichenor) with deathly pallid skin and horribly discolored teeth. The other is a man (Lon Chaney again, and this time the change in his appearance is so drastic that many 1927 viewers apparently didnít realize he was playing both roles until the concluding scenes) whose appearance is even more unnerving. He dresses in a heavy black coat and an immense beaver-fur top hat, and walks with a slithering, hunched-over gait. His face is the worst part, though: baleful, unblinking eyes in hollow, blackened sockets and a wicked, frozen grin that exposes impossibly many identical, shark-like teeth. Smithson is convinced that the pair are vampires, and if sheís right, itís bad news for Hamlin, Hibbs, and Lucille. Mr. Smiley, you see, has come to lease the Balfour place.

As the executor of Balfourís will, Sir James naturally gets a copy of the lease for his own records, and when it arrives, Hamlin is stunned to see that it is signed in Balfourís own handwriting. This causes quite an uproar in the household, and no one, as you might imagine, is more horrified than Lucille. Hamlin and Burke talk it over, and eventually agree to open Balfourís tomb and have a look inside. Iím sure you already know what they find. News of the empty grave only intensifies Miss Smithsonís conviction that the new neighbors are vampires, but it isnít until Mr. Smiley appears out of nowhere and tries to attack Lucille in her own bedroom that the rest of the bunch begin taking the maidís fears seriously. Thereís something funny going on, thoughó above and beyond the whole vampire business, I mean. Burke seems to know much more than he should about the strange goings-on next door, and begins to act more and more like heís preparing to spring some kind of trap on Hamlin, Hibbs, or both. And in fact thatís exactly what heís doing. Burke is certain that one or the other of the men is Richard Balfourís real killer, and he has a clever plan to use hypnosis to expose the culprit. As for why he needs to pretend to be a vampire while heís at it... well Iím afraid I canít help you there.

Itís entirely possible that London After Midnight was the first American vampire movieó assuming, that is, that it counts when the vampires turn out to be phony. Director Tod Browning himself wrote the story from which the screenplay was derived, and given that manís marked penchant for the bizarre, I suppose we shouldnít be all that shocked that the underlying premise makes almost no sense. With nothing but a bunch of obviously staged stills to go on, itís impossible to tell how well London After Midnight worked as a movie, but when Browning remade it seven years later as Mark of the Vampire, the results were outright painful. However, there are a couple of points in this movieís favor that might have saved it to one degree or another. First of all, the production design is brilliant. The sets here are far more convincing than those used in the remake (London, presumably, was easier for MGMís set dressers to fake than the suburbs of Prague, to which the story was inexplicably relocated for Mark of the Vampire), and if the production stills used for this reconstruction bear any real resemblance to the original film, Browning made far more skillful use of lighting and shadow to bring those sets to life. Secondly, this version of the story is more streamlined than the later one, with fewer characters and a less elaborate, more realistic murder plot. Finally, and perhaps of greatest importance, this version had Lon Chaney. Again itís hard to say how good an idea this reconstruction gives of Chaneyís dual performance, but in the stills used here, Chaney in his vampire makeup seems at least as creepy as Max Schreck in Nosferatu. The impact of Chaneyís makeup is magnified tremendously by the fact tható incrediblyó no other movie that I know of has copied it. Mr. Smiley thus looks as startling today as he did back in 1927. (As a side note, Iíd like to point out that Chaney had originally been intended to play the title role in Browningís version of Dracula, and in fact he and the director had begun talking about bringing Stokerís novel to the screen as early as 1924. Chaney is said to have devised some sort of secret makeup effect for the vampire, of which no detailed description has ever surfaced. Do you suppose itís possible that this is what the count would have looked like had that 1924 Dracula been produced?)

The idea of using nothing but stills to reconstruct a lost motion picture is definitely a radical one, and frankly, I canít imagine Rick Schmidlinís mock-up of London After Midnight having much appeal beyond a limited audience of hardcore movie nerds. Those who feel like giving it a try may be surprised, however, at how natural it all starts to seem after the first ten or fifteen minutes. On the other hand, the inherent limitations of the technique really come to the fore in the final act of the film. Thereís no good way to convey fast-moving action with so small a number of stills, and the climactic scenes end up being extremely difficult to follow. Even so, I find myself highly impressed by the sheer ambition of the project, and doubly so that it works as well as it does for as long as it does. Like I said in the opening paragraph, it isnít exactly a movie, but the still reconstruction of London After Midnight is a close enough facsimile to serve until that hoped-for day when a real, live print turns up in some weird-ass place like a 70-year-old trash heap in northern Alaska.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact