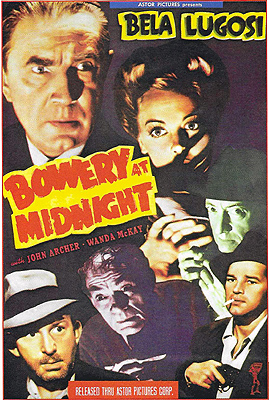

The Bowery at Midnight (1942) -**Ĺ

The Bowery at Midnight (1942) -**Ĺ

You know, I really donít think The Bowery at Midnight was originally intended to be a horror movie at all. Like the slightly earlier Monogram Bela Lugosi vehicle, Black Dragons, The Bowery at Midnight gives every indication of having started life as a script for a cheap crime potboiler instead, and having been repurposed on the basis of a perception that there were greater profits to be had in going for ghoulishness. But whereas the belatedly introduced mad science in Black Dragons makes a totally incomprehensible mess out of a picture that had only the most tenuous grasp on reason in the first place, The Bowery at Midnightís horror elements are sufficiently self-contained to intersect with the main plot only at its conclusion. Itís still a pretty damn goofy film, but it makes a lot more sense than most of the pictures Lugosi made for Sam Katzman at Monogram.

How many 1940ís horror movies do you know of that begin with a prison break? Okay, thenó you already have some idea of what Iím talking about. The man going over the wall is a safe-cracker named ďFingersĒ Dolan (John Berkes), and his escape leads him eventually to the Bowery, generally regarded as one of New York Cityís roughest neighborhoods in the early 1940ís. There Dolan overhears two transients talking about the Friendly Mission, a no-questions-asked, nobody-turned-away charity shelter run by a somewhat eccentric philanthropist named Karl Wagner (Lugosi). The mission has a soup kitchen on the first floor, dormitories on the second, and even limited medical facilities presided over by Nurse Judy Malvern (Wanda McCay, from The Monster Maker and The Black Raven). Dolan figures itíll be a great place to hide out for a day or two while he figures out what to do with himself in the long term. The last thing Fingers expects is to be recognized by Wagner. Itís okay, though; Wagner is substantially less straitlaced than he appears, and he has a job to offer the safe-cracker. Behind a secret door in Wagnerís office is another office, and behind a secret door in that, thereís a staircase leading down to the cellar, where Wagner introduces Dolan to his two accomplices, Doc Brooks (The Mad Ghoulís Lew Kelly) and Trigger Stratton (Wheeler Oakman, of Buck Rogers and The Ape Man). Actually, Dolan and Stratton have already met, having collaborated on a caper or two in their time, and the latter man vouches enthusiastically for Dolanís skill and reliability. The plan is to break into Atlas Jewelry and make off with the contents of the main safe, a job which should be well within Dolanís abilities. What Fingers doesnít yet know (and wonít be finding out until itís much too late for the knowledge to do him any good) is that Wagner is a raging paranoiac, and invariably demands that Stratton kill the second accomplice on each of his heists. Stratton is reluctant to do so in this particular case (in fact, he tries hard to talk Wagner into keeping Dolan on staff permanently), but he knows which side his bread is buttered on.

Evidently this sort of thing has happened often enough for Captain Mitchell of the NYPD (J. Farrell MacDonald, from Phantom Killer and The Thirteenth Guest) to recognize the modus operandi when the boss at Atlas discovers a dead body stuffed inside his cleaned-out safe. Lieutenant Thompson, the detective in charge of the case (George Eldredge, of Voodoo Man and Riders to the Stars), is scheduled to retire in a few weeks, so we know he canít be long for this movie. And indeed Thompson is wounded that very afternoon in an unrelated shootout with the notorious gunman Frankie Mills (Tom Neal, from Jungle Girl and The Brute Man), causing Sergeant Pete Crawford (Dave OíBrien, from The Devil Bat and Reefer Madness) to be promoted into his place. At first glance, this looks like a needless curlicue in the plot, but then Mills finds his way to the Friendly Mission, and the importance of the incident becomes clear. In fact, Wagner likes Frankie so much that he has him take Strattonís place as his pet murdereró meaning, naturally, that Stratton now goes the way of Fingers Dolan. This happens in the mission cellar, so thereís no crime scene at which to leave the body. Instead, Doc Brooks now reveals his purpose in the operation (after all, it hardly seems likely that Wagner would pay him to shoot morphine all day) by disposing of Strattonís corpse in the impromptu graveyard concealed behind yet another secret door. The graveyard chamber, meanwhile, contains a disguised trapdoor communicating to a sub-basement which Brooks apparently dug himself, where he conducts some manner of mad medical research unknown even to his own boss. Iíll give you a hint, thoughó it involves all those bodies the junkie doctor has supposedly been burying. So, to recap: a mad lab hidden somehow beneath the earthen floor of an underground cemetery, which lies behind a secret door at the back of a cellar, which is accessible through a sliding panel in the wall of an office, which is in turn concealed behind the pivoting bookcase in an office the outside world is allowed to know about. Mills trenchantly observes at this point that Wagner has more angles than any man heís ever met.

Frankie doesnít know the half of it, either. Not only is the Friendly Mission a front for all manner of criminality, but Karl Wagner himself is a frontó the man known by that name to the bums of the Bowery is really Dr. Frederick Brenner, professor of psychology! Brenner keeps his double life hidden even from his own wife (Anna Hope) by maintaining the fiction that he spends his evenings conducting research for his next book, and Mrs. Brenner only just barely thinks to wonder where her husband might be getting the money for all the expensive jewelry heís constantly ďbuyingĒ her. There is one significant point of intersection between Brennerís two identities, howeveró Richard Denison (John Archer, from King of the Zombies and I Saw What You Did), his star pupil at the college where he teaches, is the boyfriend of Judy Malvern, the Friendly Mission nurse. Richard doesnít like competing with the mission for Judyís time, and heís convinced himself that sheís cheating on him with this mysterious Mr. Wagner. Partly to prove to Judy that he can be as socially conscious as she is, and partly to keep tabs on her at work, Richard decides to write his term paper for Dr. Brennerís class on the psychology of the underprivileged, then begins skulking around the Friendly Mission disguised as a tramp. This inevitably leads him into contact with his professorís alter ego, an encounter which puts the young man in mortal danger. After all, if Wagner is paranoid enough to go through the rigmarole of recruiting and eliminating new accomplices every single time he commits a crime, then surely Brenner is sufficiently paranoid to sic Mills on anyone who discovers that he and Wagner are the same person.

Considering that Monogramís first contribution to the horror renaissance of the 1940ís was to distribute The Human Monster in the United States, I find it amusing that The Bowery at Midnight should play so much like a brain-damaged remake of that film. Once again, Bela Lugosi is a ďkindlyĒ philanthropist, using his charity operation as a blind for his criminal activities; once again, a lot of the running time is spent chasing after cops who donít end up accomplishing a whole hell of a lot; and once again, Lugosiís character gets his at the hands of a henchman whom he foolishly underrated. The big differences are that this underestimated henchman uses SCIENCE! instead of simple brute strength to exact his revenge, while the main villainís criminal enterprise is so overblown in its complexity as to be really quite ridiculous. But what else would we expect from a Sam Katzman movie, right? Rest assured, though, that The Bowery at Midnight resembles the home-grown Monogram product, too. For one thing, it displays much the same casual ruthlessness toward its characters that can be seen in The Invisible Ghost and The Corpse Vanishes, and as in those movies, all the offhand carnage has a strangely inadvertent quality to it. People in The Bowery at Midnight seem to die less because of any deliberate dramatic purpose than because screenwriter Gerald Schnitzer simply canít think of anything more to do with themó and amazingly enough, the principle applies equally to major and minor characters. Itís one of those rare instances in which incompetence fortuitously breeds effectiveness, as it earns the movie membership in the prestigious Anyone Can Die at Any Time club. Another place where The Bowery at Midnight bears the unmistakable Katzman stamp is in the epilogue scene, which is completely of a piece with the brain-curdling codas to other contemporary Monogram horror films. As with The Ape Man and Black Dragons, I donít want to give the game away, but the final scene of this picture is utterly demented, and is very possibly the kinkiest thing to happen in an American horror movie prior to the final demise of the Hays Code. And once again, the best part is that thereís every reason to believe that it came about solely as a way to tie up a loose end so glaring that not even this bunch could bear to leave it dangling, and that no one involved in The Bowery at Midnightís creation even noticed what they were actually putting up on the screen.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact