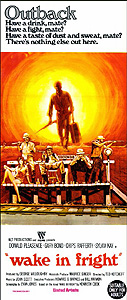

Wake in Fright/Outback (1971) ***˝

Wake in Fright/Outback (1971) ***˝

I realized a while ago that I had never seen an Australian movie made before the 1970’s. Shortly thereafter, a bit of research showed that there was a very good reason for that: there was basically no such thing. Oh, there were movies made in Australia prior to the 70’s, to be sure, but no indigenous, commercial, entertainment-oriented film industry existed there, except in the most primitive and rudimentary form. Remarkably, that was so even despite the existence of the Australian National Film Board, later renamed the Commonwealth Film Unit. Unlike the analogous bodies in most other nations where government actively nurtures the movie business, the Australian National Film Board took an extremely narrow view of its mandate, equating the public interest in film production with education in a way that produced an almost monomaniacal fixation on documentaries. There’s only so much educational celluloid on Ayer’s Rock, the Great Barrier Reef, or the mating habits of kookaburras that anybody can stomach, however, and by the late 1960’s, the Commonwealth Film Unit was under intense popular pressure to put its weight behind the creation of Australian movies that people actually wanted to see. The organization acquiesced in steps, first by establishing the Experimental Film and Television Unit to foster the avant-garde that had lately grown up in spite of determined official neglect, and then going big a year later with the Australian Film Development Corporation. Virtually overnight, Australia became not merely a producer, but an exporter of feature films, at every level of brow-altitude. Most famously, the 70’s saw the birth of the Australian New Wave, best personified by Picnic at Hanging Rock director Peter Weir. At the same time, though, there was an at least equally massive outpouring of exploitation cinema in just about every genre active in those days— plus a couple genres or subgenres seemingly unique to Australia.

And that brings me to Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright. This nearly unclassifiable oddity is one of those uniquely Australian pictures— which is a startling achievement for a Canadian director, a Jamaican screenwriter, and a largely British cast, financed to a significant extent with American money. The source material was all Aussie, though, a novel of the same name by Kenneth Cook, and it was adapted with rare fidelity. Wake in Fright may also be one of those cases where an artist or artists from outside are able to capture something vital about a culture, simply because they don’t take its idiosyncrasies for granted. At the least, that’s a line I’m reading a lot from present-day commentators Down Under, although their counterparts from 40 years ago seem to have been much more defensive about the film. Anyway, one of the neat things about Wake in Fright is that it appeared immediately before the indigenous Australian movie industry came roaring to life (the Australian Film Development Corporation debuted in between its completion and release), and can be seen as the common ancestor of both the internationally prestigious New Wave and the accompanying degenerate exploitation films. Resembling a crazed hybrid of Lost Weekend and The Heart of Darkness, Wake in Fright is simultaneously an astute, intimate character study about daily life among the downtrodden and a Mondo-ish parade of freakishness, debauchery, insanity, and violence.

The opening voiceover from the trailers says it better than I ever could: “This is John Grant— a young, handsome, intelligent schoolteacher. This is John Grant— an ugly, sweaty, desperate animal. What happened to John Grant? The Outback happened to John Grant.” To understand the predicament in which Grant (Gary Bond) finds himself, it helps to know a bit about how the Australian public education system used to handle the problem of school staffing in remote, rural areas. One look around Tiboonda, where Grant is posted, should tell you how hard it is to convince people to work as teachers in the Outback— apart from Grant’s one-room schoolhouse, the pub where he rents a room, and the ramshackle boarding platform beside the train tracks, there is literally nothing but empty, featureless desert as far as the eye can see in all directions. You have to wonder where Grant’s dozen or so pupils come from in the first place! To create a school system at all under such conditions, the government found it necessary to resort to a kind of indentured servitude. The price of a government scholarship to a university teaching program was a bond to spend some defined period (usually three years) at an Outback school before being considered for more desirable postings, on pain of forfeiting some large amount of money. Grant’s bond specifically is worth $1000, and so much has he grown to hate Tiboonda in the short time he’s been there that he’d gladly fork over the money to buy his freedom, if only he actually had $1000. When we join Grant, it’s the last day of classes before the Christmas holiday, and he can barely wait to hop the afternoon train to Bundanyabba, the nearest settlement big enough to support even a short-range airport, for his flight home to Sydney.

This being apparently Grant’s first year teaching, he’s never spent any time in Bundanyabba— “the Yabba” to its inhabitants— before. His plane doesn’t take off until tomorrow afternoon, though, so he’s got little choice but to get acquainted with the place now. His first stop is a bar which officially closes at the ridiculous hour of 6:30 in the evening, but which in practice is hopping all night long. There Grant meets Jock Crawford (Skullduggery’s Chips Rafferty), the Yabba’s one-man police force. And for those of you keeping score, yes— that does mean that instead of busting this bar for staying open past statutory closing time, the local constable is hanging out in it, getting drunk. In a way, though, it rather makes sense. Crawford knows that any trouble in town is likely to start in a place like this, so he might as well be there to put the brakes on it. Jock buys John an immense number of beers over the course of the night, refusing to take “no thank you” for an answer, and expressing subtle but unmistakable disapproval when the teacher attempts to drink them at a sensible, temperate pace. Eventually, though, Grant convinces the intrusively friendly cop that no further boozing will be possible for him unless and until he gets something to eat. Crawford therefore leads the way to a nearby tavern, where a person can get a steak along with their West End Bitter.

Ironically, that second stop is where John gets himself into trouble. Liquor and griddle-fried meat are not the only attractions at the tavern. In back, there’s a big, dark room where crowds of men gather to play two-up, a primitive game of chance that involves betting on the outcome of a double coin-toss. At first, Grant is as dismissive of two-up as he is of everything else in Bundanyabba, but then he falls into conversation with an odd little man called Doc Tydon (Donald Pleasence, from Circus of Horrors and The Devil Within Her). Tydon really is a doctor, but since he’s also a barely-controlled alcoholic, he’s no longer able to practice medicine in what Grant would think of as the civilized world. Here in the Yabba, however, Tydon’s drunkenness is just the slightest bit outside the norm, and he’s able to live well enough for his modest purposes by bartering his expertise and availing himself of his neighbors’ compulsive generosity. The other salient fact about Tydon is that he’s a thinker in a place full of doers, and he’s able to intellectualize for Grant some of the more perplexing aspects of local culture. After talking to Doc for a while, John gets it into his head to play a few rounds of two-up, and to his delighted surprise, he winds up winning several hundred dollars. In fact, he pockets so much money that another win would enable him to buy out his bond to the Department of Education. Now a clear-headed, sober man might have the sense at this point to set aside those winnings, and commit himself to saving the last two or three hundred bucks out of his regular pay over the coming semester (or year, or whatever). But Grant is neither of those things right now. He’s drunker than he’s ever been in his life, and desperate with loathing for his job. So John goes back to the two-up room, and loses every penny he just won. Then he loses his last paycheck for the term, too. When he wakes up the next morning with the queen mother of hangovers, he’s got just two dollars in his pocket, and no way to pay for the flight into Sydney.

Oh— and did I mention that it’s Saturday? That means nobody’s in at the local employment office, which in turn means that Grant can’t even pick up a day-labor gig to raise the needed cash. He ends up moping around the shitty little town until he’s unexpectedly taken under the wing of Tim Hynes (The Killing Hour’s Al Thomas), the closest thing to a middle-class person he’s seen since coming to the Outback. Bourgeois for the Outback is a far cry from Sydney-bourgeois, however. Hynes gets Grant drunk again (oh, no…), listens to his story, and ultimately invites him home for the evening. Tim’s 30-ish daughter, Janette (Sylvia Kay), seems none too happy about that, but at the same time long resigned to her dad pulling such capers. Then a couple of Tim’s friends drop by, miners by the names of Dick (Jack Thompson, from Flesh & Blood and Feed) and Joe (Peter Whittle), followed in short order by Doc Tydon. Literal gallons of beer later, Grant is officially one of the blokes, even if he did call his status into question early on by talking to and permitting himself to be seduced by Janette. (A man wanting to spend time with a woman? What is he, some kind of poofter?) Grant won’t remember very much of the night’s events when he awakens late the following afternoon in Tydon’s barely habitable shack.

This is where Grant really gets swallowed up by Outback living. Since there’s basically nothing else for him to do, John spends the whole evening hanging out with Doc, listening to him expound upon his peculiar philosophy and absorbing his insights into life in the Yabba. Come sunset, he accompanies Doc, Dick, and Joe on a savagely drunken kangaroo hunt that ends with John beating one of the animals to death with the butt of a rifle. After that, it’s off to yet a third bar to get even drunker, where Grant’s companions trash the place in an eruption of pointless, stupid, brute fury. Grant himself would no doubt have participated, too, had he not already passed out by then. Eventually, Grant and Tydon manage to stagger back to the latter’s shack, at which point the two men cap off the night’s adventures by (apparently) having sex. Waking up half-naked on top of the disgraced doctor is the final straw for John. He’s getting the fuck out of Bundanyabba, even if he has to walk to Sydney!

The critical fashion of the moment seems to be to describe Wake in Fright as a movie “about Australia,” and I suppose that’s accurate enough. It’s certainly a cultural snapshot of sorts, hinging as it does on an internecine clash of attitudes and folkways between urban and rural, coastal and inland, middle- and working-class. Neither side is presented in at all a flattering light, though, which probably explains why Australian audiences took such exception to this movie when it was new. The sins of the Yabba are more immediately obvious, of course. The violence, the drunkenness, the misogyny, the bizarre homoerotic homophobia— it’s easy to dismiss this entire society as incurably backward if not actually insane. But then, John Grant isn’t exactly a prize, either. I mean, just look at what he’s doing the first time we see him. Whereas virtually every other movie or TV teacher in history gets introduced while lecturing right up to the ring of the dismissal bell, Wake in Fright starts with Grant and his pupils all sitting silent and motionless, doing literally nothing but to run out the clock on the term. Forget about those idealistic teachers you’ve seen in everything from Stand and Deliver to Class of 1984, who fight to bestow the gift of enlightenment upon the disadvantaged and institutionally neglected children of the poor. This guy doesn’t give two shits about the struggles his students face, nor indeed does he care much about whether or not they learn anything from him. The whole of his professional attention is focused on the release of his bond to the Department of Education, taunting him from its perch two and a half years in the future. And when John comes to Bundanyabba, and is forced to interact with people who might as well be the parents of those kids at the Tiboonda schoolhouse, we see that he regards them no more highly. Smug and nakedly condescending even in the face of earnest overtures of friendship, he makes no effort to disguise his contempt for the Outback, its people, and their ways. It’s supposed to be horrifying when Grant loses his grip on himself, degenerating as far as the most wretched man in the Yabba— and it is— but the truth is, he was always kind of a fucker. It’s just that before, he was a civilized fucker.

Now all that sounds pretty condemnatory, so again it’s no wonder that the initial Aussie reaction to Wake in Fright involved so much, “Who the fuck do these Brits and Canadians and Jamaicans and shit think they are?!” If you look closely, though, you’ll see that Kotcheff never passes judgement on either Grant or Bundayabba. On an editorial level, the whole movie is summed up by the conversation between Grant and Tydon that precedes the former’s deceptive run of luck at two-up. Doc, originally a city man himself, has no trouble recognizing the teacher’s revulsion at the Yabba and its culture. When pressed to talk about it, John complains of “the aggressive hospitality, the arrogance of stupid people who insist you should be as stupid as they are,” and he’s exactly right. That’s the very thing that makes Jock Crawford and Hynes’s miner friends so immediately repellant, even before you get a chance to watch them properly in action. But Doc also has it exactly right when he replies, “Discontent is the luxury of the well-to-do. If you’ve got to live here, then you might as well like it… It’s death to farm out here. It’s worse than death in the mines. You want them to sing opera as well?” I gather that that generous evenhandedness is what has increasingly won over viewers Down Under as the passage of time diminishes the sting of the “My God— is this what we look like to outsiders?!?!” effect (although I’m sure the proliferation of internationally released Australian movies that don’t make the entire country look like a nest of weirdos and lunatics had something to do with it, too).

So far, I’ve been talking about Wake in Fright mostly in its capacity as a precursor to the Australian New Wave. Now it’s time to look at it as the scummy trash that it spends just as much of its time being. Item number one on that agenda simply has to be the kangaroo hunt. To create that scene, Kotcheff and his crew tagged along on a real midnight roo cull, intercutting the genuine hunting footage with material shot on a different night featuring the actors rampaging around the desert in Dick’s heavily modified ‘59 Ford. Kangaroo culling (although surely necessary in some form to address the fallout from 200 years or so of gross environmental mismanagement) is an extremely controversial practice in Australia, not least because so much of it was done in exactly the grotesque and slipshod manner captured here. The hunt is easily the most disturbing sequence in the film, and trying to sort out the ethical issues tied up in the way Kotcheff handled it makes my brain sore. Does the fact that these animals would have been killed regardless mitigate the wantonly exploitative manner in which their deaths are presented? Could shining a light on the hooliganism of early-70’s kangaroo culls have contributed to the public outcry that led to at least slightly tighter controls being placed on them in later years? Might the presence of Kotcheff and his cameras have encouraged the hunters he filmed to act up, conducting themselves even more savagely than they ordinarily would have? Or alternately, is it possible that this hunt, horrifying as it is to watch, represented the cullers’ best behavior? Whatever conclusions you come to, anybody seeking out Wake in Fright owes it to themselves to consider first whether they’re ready for a protracted sequence of animal slaughter as distressing as nearly anything in an Italian Mondo or cannibal movie.

Otherwise, Wake in Fright’s main attraction as sleaze is Donald Pleasence’s marvelously unhinged performance. Doc Tydon is a remarkable achievement. From the moment he and Grant meet, he’s like the little cartoon devil standing on the teacher’s shoulder, tempting, goading, and cajoling him into doing things he’ll regret later. At first, I expected Jock Crawford to do that job (heaven knows he bids fair for it with all that beer he pours down John’s throat), but this movie’s creators were much smarter than that. The frankly thuggish cop has Grant on his guard from the get-go, but Tydon, like Hynes, can play to John’s class prejudices. Tydon, after all, is a doctor. A transplant from Sydney. An intellectual. Who better to lead Grant into perdition than someone who understands and at one point probably shared his values? It isn’t just that Doc is there to egg John on to each new self-abasement, either. When you really look at it, what Grant is doing throughout his whole time in Bundanyabba is acting on something the doctor said about the locals in their first encounter: if he’s got to be there, he might as well like it. Pleasence is a fine choice for such an Outback Mephistopheles, the veritable incarnation of the Imp of the Perverse. His soft voice, small stature, and doughy physique make him seem outwardly harmless, but few actors ever matched Pleasence for deviousness. By the time you realize that Tydon has befriended Grant mainly because he relishes having somebody to pull down to his level, the damage is already done. All the same, Pleasence’s Tydon remains infectiously likable, precisely because he’s such an unapologetic little troll. He’s a man who has found his niche, who has adapted to it perfectly, and who is having so much fun there that he wants to share the experience with as many people as possible. And if that sharing breaks something inside them, well… this is the Yabba. It’s mad to be sane out here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact