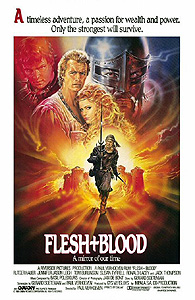

Flesh & Blood/The Rose and the Sword (1985) ****

Flesh & Blood/The Rose and the Sword (1985) ****

There’s something interesting going on these days with depictions of the Middle Ages (broadly construed here to include the Renaissance, which wasn’t actually that much different unless you were an artist or a scholar), both the real ones and the made-up counterparts that have been a staple of fantasy fiction ever since “fantasy fiction” became a genre in the early 20th century. Whereas the traditional approach has been to take at face value the notion of an Age of Chivalry handed down from authors who actually lived in days of old, when knights were the last thing the average person ever wanted to see up close, it’s now becoming increasingly common to find the Medieval world portrayed more critically and with less romanticism. Consider on one side “The Tudors,” and on the other, “A Game of Thrones.” One historical melodrama and the other overt fantasy, both shows take as their starting point a vision of Medieval and Renaissance Europe as a cesspool of violence, brutality, and ruthless misgovernment, where a noble title is the surest mark of a megalomaniacal scoundrel. And significantly, both are (or were, in the case of “The Tudors”) massive pop-culture phenomena. That being so, I believe that this might finally be the time for Flesh & Blood to receive the attention it deserves. Paul Verhoeven’s first English-language movie, Flesh & Blood has been understandably overshadowed by RoboCop for the past quarter-century, but if you’re looking for a Medieval movie with all the filth and squalor of the real 15th century, it’s about as strong an example of the form as you’re likely to find.

The year is 1501 (which, okay, makes this the 16th century, but only just barely), and the place an almost maximally vague “Western Europe.” There’s a siege on, with Count Arnolfini (Fernando Hulbeck, from Pyro and Let Sleeping Corpses Lie) striving to conquer some other fellow’s fortified city, mainly because that’s just what men of his station do with their free time. The city walls are strong, the defenders numerous and determined, and so Arnolfini has bolstered his forces with a company of mercenaries led by the almost unimaginably deadly Martin (Rutger Hauer, of Hobo with a Shotgun and Buffy the Vampire Slayer). I’m not sure how many men Martin has under his command, but it must surely be more than the four we get to know well: Karsthans (Brion James, from Blade Runner and The Horror Show), Summer (John Dennis-Johnston, of The Beast Within and Streets of Fire), Orbec (Bruno Kirby), and Miel (Simon Andreu, from Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion and The Blood-Spattered Bride). In any case, Arnolfini’s deal with the mercenaries is that they will be allowed to plunder the city for 24 hours if they succeed in taking it. When the victory comes, however, Martin, his men, and their camp followers— including a slightly mad cardinal (Ronald Lacey, from Crucible of Terror and Red Sonja) and a boisterous pack of whores led by Martin’s lover, Celine (Susan Tyrrell, of Powder and The Offspring)— prove so adept at looting and pillaging that the count fears the utter despoliation of his prize. Arnolfini therefore orders his right-hand man, Captain Hawkwood (Jack Thompson, from Wake in Fright and Man-Thing), to pacify them and drive them out beyond the walls, bargain or no bargain. Hawkwood is as good at his job as Martin and the gang are at theirs, and the next thing the mercenaries know, they’ve all been expelled, their hard-won booty confiscated along with the weapons whereby they earn their livings.

Count Arnolfini has a son, a scholarly lad by the name of Steven (The Time Guardian’s Tom Burlinson), who is just about at the age where custom demands that he start shopping for a bride. Steven wants none of that, however. The stereotypical life of a nobleman is not for him, with its wars and politics and dynastic marriages. He’d rather spend his days adding to the accumulating sum of human knowledge and inventing useful devices. He’ll marry at some point, sure, but not now. Of course, when Steven says that, he hasn’t yet met the girl whom his father has in mind to become his wife. When the lady Agnes (Jennifer Jason Leigh, from The Hitcher and Eyes of a Stranger) arrives at the newly conquered castle, Count Arnolfini is sure the boy will change his mind. He’s right, too, but it isn’t the prospective bride’s beauty that sways Steven. What turns the future count’s crank is Agnes’s sharp and inquisitive mind. Don’t go looking for the kids’ gift registry at Crate & Barrel just yet, though. Aristocratic wagon trains are tempting targets for banditry, and Martin’s mercenaries have not dispersed as Arnolfini hoped they would. On the way home from her visit, Agnes and her entourage come under attack. Agnes herself is inevitably reckoned the most valuable prize of all when the brigands assess their windfall, both for her eminent rapability and for the humongous ransom she would no doubt fetch from her loved ones. 1501 communications technology being what it is, Arnolfini and his son learn of the abduction long before the girl’s father, and soon Steven, Hawkwood, and a detachment of the count’s soldiers are chasing around the countryside in search of Martin and his band.

This is where things turn complicated for all concerned. Arnolfini’s forces haven’t been in the field long before Hawkwood comes down with the bubonic plague, effectively immobilizing them until he either recovers or more likely dies of the disease. Meanwhile, the chance discovery of a religious statue buried in a battlefield mudhole gives the cardinal the idea that Martin is being guided by Saint Martin, from which point the mercenary company starts looking more and more like a Medieval Manson family. The band’s accustomed scruffy nomadism is obviously no life for people favored by a saint, so Martin leads them in seizing a poorly defended castle as the first step toward ennobling himself and his followers. Obviously that’s going to make things more difficult for Steven when he finally catches up with his quarry. The most serious complications, however, are those arising from the meeting of Martin and Agnes. As I said, Agnes is no dummy. She figures out right in the middle of being raped by him that Martin has taken a special interest in her, and she wastes no time exploiting that interest to keep from becoming the common property of the whole mercenary army. She recognizes only a day or two later that her best bet for staying alive and healthy is to feign acceptance of the mercenaries and their ways, even if that means snubbing Steven when he attempts to negotiate her release. She even capitalizes on her familiarity with courtly etiquette to position herself as tutor to her captors in their efforts to acquire a veneer of respectability. A funny thing, though… After a week or two playing the role of princess among Martin’s whores, Agnes starts finding it hard to distinguish between her genuine desires and those of her character, so to speak. Some of the blurring is almost certainly what we would now call Stockholm Syndrome, but some if it might just be a real developing affection for Martin and a similarly developing appreciation for the wild and carefree lifestyle of his followers. Agnes is going to have to sort that out pretty soon, too, because Hawkwood does indeed beat the plague thanks to Steven’s knowledge of the latest Arabian medical techniques, and the battle for control of her is about to begin in earnest.

Although it plainly owes its existence to the vogue for sword-and-sorcery movies that was starting to wind down in 1985, Flesh & Blood is actually something much rarer, possibly even unique. It’s a sword-and-science film. What would be the wizard’s role in a normal Medieval fantasy tale is here played by Steven, whose command of the new and rediscovered knowledge turned loose by the spreading Renaissance enables him to do things only slightly less wondrous than casting lightning bolts or conjuring up elemental spirits. Hawkwood survives his brush with the Black Death because Steven rejects Aristotelian humor-based medicine in favor of empirically derived techniques recommended in an Arabic medical treatise, with the result that even Arnolfini’s court doctor is eventually forced to concede the effectiveness of “heathen” surgical practices. Steven’s engineering talents produce a siege engine that almost overcomes the defenses of Martin’s stolen castle before the mercenaries use another of Steven’s own inventions to destroy it. And in the end, it’s Steven’s use of the plague as a biological weapon that makes possible Martin’s defeat. Notice, however, that none of these things are portrayed in a strictly realistic manner. Now it’s possible that Paul Verhoeven is just doing what filmmakers usually do in the face of science and technology— getting it all wrong— but I suspect there’s something more sophisticated going on here. Remember that Steven is the only character who can be considered anything like educated in the modern sense. My God, Martin needs Agnes to show him how to operate a fork, and for reasons we’ll discuss shortly, we probably shouldn’t bet on even the cardinal knowing how to read or write. I think Verhoeven might be trying to show us Steven’s achievements as they look to everyone around him, to add to the overall picture of Medieval backwardness by demonstrating an extremely low Clarke’s Law threshold. To these people, even lancing a bubo is indistinguishable from magic.

Other characterizations are just as unusual as Steven’s, and similarly operate as stealth world-building. Take the cardinal, for example. It’s natural to have certain expectations of high-ranking religious figures in Medieval movies, but this guy doesn’t fit into any of the regular boxes. To be sure, there is a tradition of warrior priests, warrior monks, and even warrior bishops in tales of the Middle Ages (indeed, that tradition is the reason why Dungeons & Dragons offers clerics as a character class), but when have you ever seen a cardinal as a mercenary camp follower? By making Martin’s pet clergyman a cardinal, Verhoeven is reminding us where we are. In the 15th and 16th centuries, it was a disgracefully routine practice for popes to straight-up sell cardinalships. The idea was not just to raise money, but also to pack the Vatican with yes-men who could be counted on to favor the current pontiff’s hand-picked successor (often a nephew or a bastard son, who were granted their own cardinalships as a matter of course) at the next conclave. Education, personal morality, and even interest in religious matters were irrelevant; loyalty to the pope and support for his designs were the only qualifications needed. We can therefore be reasonably sure how this particular cardinal came by his snazzy red hat, and indeed his behavior throughout the film is hardly a credit to his vocation. And yet it’s also obvious that the cardinal is weirdly sincere about all the St. Martin business, however cynically self-serving (or Martin-serving) the specific instructions from on high may be. The cardinal is both con-man and true believer, even to the extent of being a true believer in his own cons.

The most compellingly contrarian characterizations, however, are certainly those of Martin and Agnes. Romances developing between women and their captors are among the commonest commonplaces of stories set in this era, and most of the time, there are certain rules governing how the trope plays out. The woman will be pure and virginal, often to the point of haughtiness, and although her attitude and behavior toward the man changes over the course of the story, her scruples do not. What happens is that either the man permits himself to be softened and civilized by his love for the woman, and thereby becomes someone whom she can love in return, or some change of perspective allows the woman to see that he was really that sort of person all along beneath his rough and barbarous exterior. Flesh & Blood teases us for a moment with the possibility that it’s headed in the expected direction, but Martin’s “nobody gets to rape Agnes but me” stance never really signifies more than the universally accepted principle that the bandit chieftain always gets first pick of the spoils. Instead, what we get is a ruthlessly pragmatic relationship on both ends, with Agnes doing her level best to top from below, as the kinksters say. For Agnes, the affair is entirely about exploiting her position as the alpha-dog’s bitch to maintain her safety from the rest of the pack. To the extent that her attitude toward Martin and the mercenaries evolves, it isn’t a question of finding hidden depths of gentleness in them, but of finding hidden depths of savagery in herself. Martin becomes attractive to her because he really is that big a bastard, and what he offers her is the freedom of utter lawlessness— which has to hold some appeal for anybody whose life choices are as tightly circumscribed as a late-Medieval lady’s. Flesh & Blood is at its most interesting when it presents Agnes’s shifting loyalties as a matter of rational decisions which she makes for herself, certainly for the first and possibly for the last time in her life. And it’s at its second-most interesting when it refuses to treat Martin as the villain, however vile it shows him to be. Hero vs. antihero (as opposed to antihero vs. villain) is a conflict structure we don’t see nearly enough of in the movies, even without the intriguing extra wrinkle of an increasingly anti-ish heroine pulling both parties’ strings.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact