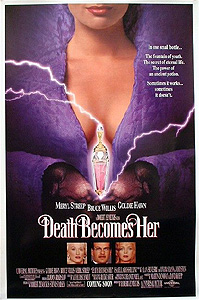

Death Becomes Her (1992) ***½

Death Becomes Her (1992) ***½

I honestly had no idea that Robert Zemeckis didn’t always suck. That’s funny, because I’ve seen some of his early, non-sucking movies, but the last time I watched Back to the Future and Romancing the Stone, I was a kid not a bit concerned with things like who directed the movies I enjoyed, and I missed the credits when I finally caught up with Who Framed Roger Rabbit? a few years back. Zemeckis entered my consciousness under his own name only with Forrest Gump, one of the most profoundly loathsome films of the 1990’s, and stayed there on the strength of his dreadful, zombie-eyed motion-capture cartoons, which helped to kill off traditional animation with one hand while defeating the entire purpose of the art form with the other. I was therefore in no way prepared for Death Becomes Her. At the opposite pole of the cosmos from the mawkish bullshit Zemeckis has specialized in for the past twenty years, Death Becomes Her is more like something Paul Bartel would make if only someone would front him enough money. It’s a pitch-black, pitch-perfect satire of Hollywood phoniness and superficiality, built around the relationship between two old friends who, deep down, have always hated each other’s guts.

Madeline Ashton (Meryl Streep) and Helen Sharp (Goldie Hawn) have known each other since they were kids, and although I’m not exactly sure how long that’s supposed to have been, it’s clear enough that decades are the appropriate unit of measure. Throughout all that time, they’ve remained ostensible friends even though Madeline is a backstabbing bitch who takes obvious pleasure in wrecking every piece of Helen’s life that she can get her hands on. Maybe the whole Hollywood thing goes some way toward explaining it. Madeline became a stage and screen actress of fair renown at some point, and it might be validating for an insecure person like Helen to be able to say that she’s friends with a real, live celebrity. Whatever the reason, when Helen finds herself engaged to marry plastic surgeon Ernest Menville (Bruce Willis, from 12 Monkeys and The Sixth Sense)— himself a major star in his field— she feels compelled to show him off to Madeline. With that in mind, the couple go to visit Madeline backstage at the theater where she’s performing in (get this) a musical version of Tennessee Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth. Helen knows this is a risky thing to do; her best enemy has made a habit for years of stealing Helen’s boyfriends. Furthermore, Madeline has an excellent reason to poach Ernest in particular, because she’s been thinking lately that she’s starting to show a little too much of her age. Ernest and Madeline hit it off easily at their introduction, driving Helen practically crazy with fear and jealousy. The doctor protests that any interest he might have developed in Madeline is purely professional— so of course the next thing we see is him getting married not to his erstwhile fiancee, but to that scheming harpy instead.

Seven years go by, and Helen withdraws ever deeper into depression, obsession, and persecution mania. She becomes enormously fat, doing nothing all day but to stuff snack food into her face while watching the death scene from one of Madeline’s movies over and over again on her VCR. She loses whatever job she had, gets evicted from her increasingly foul apartment, and winds up in a mental hospital where she infuriates staff and fellow patients alike by talking about nothing but Madeline Ashton whenever anyone will listen to her. Finally, though, one of Helen’s doctors (Alaina Reed-Hall) accidentally breaks through her despondency. Thoroughly sick of her patient’s shit, the doctor tells Helen that she’s never going to make any progress unless and until she eliminates Madeline from her thinking altogether, and concentrates strictly on herself. What the doctor says isn’t quite what Helen hears, however. What penetrates Helen’s spiritual paralysis is that one word: “eliminate.” Yes— that’s it exactly. Eliminate. Why didn’t she think of that herself ages ago…?

Seven more years pass, after which we look in on Madeline and Ernest. It’s apparently not been a happy decade and a half for those two. Madeline is more fixated than ever on preserving her looks against the advancing years, and is virtually addicted to cosmetic surgery. She can’t get her operations from Ernest anymore, though, because he’s lost his license to practice. It’s hard to turn out good work when you’re drunk all the time, after all, but evidently it’s even harder to live with Madeline Ashton when you’re sober for more than five minutes at a stretch. Ernest is now reduced to plying his skills reconstructing the human form as a mortician, in which capacity he excels nearly as much as he did in his old line of work. Still, Ernest’s second career is not one that his wife respects, any more than she respects anything else about him these days.

Re-enter Helen Sharp. Since the last time we saw her, she’s gotten her shit together to an amazing extent. Slimmed back down to her weight of fourteen years ago, she also has a new and altogether more flattering look, to say nothing of an unprecedented social confidence. It wouldn’t be going too far to say that Helen has become downright glamorous. Naturally Madeline is appalled. So, in his own way, is Ernest, who suddenly realizes what he threw away in exchange for his present life of misery. Luckily for him, it soon becomes apparent that Helen is looking to steal him back from Madeline. Madeline, for her part, isn’t going to stand for that, and as always, her response to the challenge is another round of surgical touchups. The trouble is, she just had one of those a few months back, and her regular doctor (Ian Ogilvy, from The Conqueror Worm and Puppet Master 5: The Final Chapter) will not consent to rebuilding her face yet again so soon. Still, Dr. Chagall understands Madeline’s plight, and although his professional ethics prevent him from okaying another operation, they don’t stop him from making a referral. Chagall happens to know a woman by the name of Lisle von Rhuman (Isabella Rossellini, of Blue Velvet and Infected), whose techniques for restoring youth and beauty are second to none. They’re just not approved by any professional association or regulatory body, so she has to do her work in the strictest secrecy. Madeline strikes Chagall as desperate enough to keep her mouth shut, so he hands over von Rhuman’s card.

Lisle von Rhuman’s techniques are not officially certified because she isn’t a plastic surgeon, a nutritionist, a personal trainer, or anything else of that nature. Lisle von Rhuman, rather, is a witch. A very well-paid and successful witch, too, if we may judge from the German Expressionist castle where she lives and works. She claims to be 71 years old, but her magic keeps her looking like the Los Angeles version of the upper 30’s. Von Rhuman’s youth potion can do the same for Madeline, too, if she’ll sign various confidentiality agreements, but that’s far from all. If von Rhuman is to be believed, her formula can actually confer immortality! Madeline is skeptical at first, but a quick demonstration of the glowing, pink liquid’s power convinces her that the Hollywood alchemist is on the level. On her way out the door, though, von Rhuman gives her a curious warning: take care of her body, because she’s going to be needing it for a long time.

Meanwhile, Ernest and Helen are plotting to get rid of Madeline. Divorce, the obvious approach, is out on financial grounds, since Ernest has already drunk up every penny he ever made on his own. That leaves murder— which, you’ll recall, has been Helen’s ultimate aim ever since that fateful talk with the hospital psychiatrist. The two adulterers meticulously plan a phony accident, but Madeline ends up succumbing to something like the real thing instead. She and Ernest get into a huge fight when she comes home from von Rhuman’s, and their quarrel reaches its climax at the top of the big, marble staircase leading upstairs from their foyer. When Madeline loses her balance in the heat of the moment, Ernest is too pissed off at her to feel much like arresting her fall; she breaks both legs, her neck, an arm, and a collarbone on the way down. Nevertheless, Helen is incensed when Ernest calls to report the serendipity. I mean, the whole point of rigging an accident was to insulate themselves against suspicion, yet here Ernest is killing his wife in their own foyer. Official scrutiny is the least of their worries, though, because immortality in the context of von Rhuman’s witch’s brew apparently means immortality. Dead or not, Madeline isn’t going anywhere, and she’s extremely upset when she learns about her husband’s little scheme. Helen (not yet apprised of her rival’s resurrection) comes over to make sure Ernest disposes of the body to her satisfaction, and thereby gives Madeline the chance to blow her away with a shotgun. But since Helen, too, got her renewed looks from Lisle von Rhuman, death doesn’t slow her down any more than it does Madeline. And now we see what the witch meant about her customers needing to take care of their bodies. The two rivals may be immortal, but they’re both still dead now. Corpses don’t heal, so Madeline is stuck with half her bones broken, while Helen is stuck with a gaping hole through the middle of her torso. It doesn’t take the women long, though, to remember that Ernest is an ace mortician. He renders injuries like theirs presentable all the time, and they’ve got more than enough dirt on him to extort whatever reconstructive services they may require for the rest of his life. Now they just need to make him imbibe von Rhuman’s potion, too, so that the rest of his life will be coterminous with the rest of theirs.

In between the resurrection of Madeline and the commencement of open hostilities with Helen, there’s a sequence that embodies everything good about Death Becomes Her. Neither Madeline nor Ernest understands yet that she has become an effectively indestructible zombie, and both temporarily regard her seemingly miraculous survival of the fall down the stairs as a second chance to do right by each other. Nevertheless, it’s clear that Madeline needs some kind of medical attention, so off to the hospital they race. There, Madeline is looked over by a doctor (longtime director, producer, and character actor Sydney Pollack), who subjects her to one examination after another until there’s no more room for doubt that his patient is a living dead woman— at which point he excuses himself, steps out of the examining room, and promptly dies of a heart attack. Never would I have guessed that Robert Zemeckis, Meryl Streep, or Bruce Willis had a bit like this in them. (Pollack, who does the heaviest lifting in the hospital scene, is enough of an unknown quantity to me that I had no expectations of him one way or the other.) The tone is so gleefully morbid, the comic timing so effortlessly exact. Streep is a fine actress, certainly, but that’s just it— she’s a fine actress, whereas this sequence and indeed the entire movie are unabashedly gross. And Willis! My God, this is John McClane we’re talking about. This is Hudson Hawk, Joe Hallenbeck, that jerk-ass baby in Look Who’s Talking. This is Mr. Macho Sarcasm himself, yet here he is in a role that could have been tailor made for Rick Moranis. I’ve never seen Willis play such a hapless, high-strung putz before, but he’s great at it. Of course, I might not have been so blindsided had I remembered about Zemeckis’s early career. Looking back on what I now know to be his work from the 80’s, he was usually good for at least a few such moments of mordant brilliance.

Still, Death Becomes Her goes further, into darker and more outré territory, and achieves such consistently funny results that only the existence of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? prevents me from nominating this movie as Zemeckis’s secret masterpiece. The two films have more in common than they might immediately seem to, as well. Death Becomes Her, too, has the manic, rubber-faced violence of a mid-century Warner Brothers cartoon, especially when Helen and Madeline are going at each other with all the underhanded intensity of Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck trying to bamboozle Elmer Fudd into thinking it’s the other fellow’s hunting season— and to much the same immediate result. Meanwhile, both movies derive a lot of their humor from smartly skewering life in Hollywood, although they naturally aim their satirical punches in somewhat different directions. In Death Becomes Her, the target is the town’s collective obsession with youth and beauty, and the seemingly insane lengths to which entertainment-industry people will go to preserve those things, or at least the illusion of them. After all, what’s a little black magic to someone who already thinks it’s a good idea to inject botulism into their face? There’s also a secondary focus on the massive insincerity, disloyalty, and selfishness that showbiz culture rewards. All three of the people at the story’s core are fairly horrible, backstabbing advantage-seekers among whom the one deep and genuine emotion is the women’s mutual loathing. There’s a hint of “Fawlty Towers” here, in that much of fun of Death Becomes Her lies in watching the protagonists dig themselves ever deeper into holes of their own making.

My favorite aspect of Death Becomes Her, though, is its examination of a uniquely feminine form (at least in my experience) of toxic relationship. Ever since college, when I started dating a girl who had not one but two best enemies, I’ve been queasily fascinated by the idea that for many women, hatred is not necessarily an obstacle to a lifelong friendship. The bond between Helen and Madeline is impressively well observed, as each insult, each betrayal, each outmaneuvering brings the two women that much closer together, until they loom far larger in each other’s lives than anybody either of them actually likes ever could. Best of all is the blackly hilarious, devilishly logical conclusion to which their relationship comes: after they kill each other (or conspire to kill in Helen’s case), it’s finally possible for them to be truly friends.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact