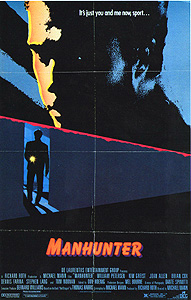

Manhunter (1986) ***

Manhunter (1986) ***

Do you remember what a big deal The Silence of the Lambs was when it came out? I mean, how often does a movie about a cannibal psychiatrist and a cross-dressing serial killer make the cover of Newsweek? It had been the first movie in a good, long while that I was really excited about seeing, and the first such film in even longer than that which had so greatly exceeded my expectations. What I did not realize at the time was just how much history it had behind it. I had never heard of Thomas Harris, and I missed the notation in the opening credits identifying The Silence of the Lambs as having been based on his novel of the same name. Consequently, I also had no idea that the book had been a sequel to an earlier novel called Red Dragon, nor did I know that there was a film adaptation of the latter work floating around as well. The tip-off came when the girl I was dating at the time (and with whom I had watched The Silence of the Lambs) saw a commercial on TV for an upcoming broadcast of an old movie called Manhunter. You can imagine the tone of the commercial in question— something very close to the tag-line on the recent Anchor Bay home video release, as a matter of fact: “Hannibal Lecter’s legacy of evil begins here!” Of course, I’ve never been terribly good about remembering television schedules, and though my curiosity was piqued, the idea that Manhunter was coming on TV in a couple of days slipped my mind for good within a couple of hours. And for whatever reason, it’s taken me this long to get around to checking it out. It’s no Silence of the Lambs, and viewers who come to it looking for the beginning of “Hannibal Lecter’s legacy of evil” will leave sorely disappointed, but it’s a damn cool movie nevertheless.

Somebody is running a Super-8 movie camera; we’re looking through its viewfinder ourselves. The extraordinarily tall cameraman creeps around the front end of his customized van, and lets himself into what we can already tell is somebody else’s house through the sliding glass door to the kitchen. Then he goes upstairs and into a bedroom, where he shines his flashlight in the faces of the man and woman sleeping therein. It must surely come as a relief to the more squeamish members of the audience that the scene comes to an abrupt end at this point.

That was in Atlanta. Now in Captiva, Florida, we meet retired FBI detective William Graham (William Petersen, of The Beast and Fear) as his old boss, Jack Crawford (Dennis Farina), tries to convince him to come back to work to help him on an especially difficult case of a sort for which Graham had a particular talent. Evidently, the Atlanta couple and their children were not the first victims of the man who killed them; another family were found slaughtered in Birmingham in precisely the same distinctive manner almost exactly one lunar month ago. Crawford says he needs Graham’s knack for getting inside the heads of psychopaths— no one on his present staff has anything like that special empathy, and the killer has been much too careful so far to leave much in the way of physical evidence. The FBI know his approximate size, his hair color, and his blood type, and they’ve got casts of his teeth taken from the bodies of his victims. Otherwise, they’ve got jack shit. Will’s wife, Molly (C.H.U.D.’s Kim Greist) and son Kevin (David Seaman— must’ve sucked to be him in seventh grade, huh?) hate it, and Graham himself isn’t exactly happy about it either, but his conscience demands that he take on the job.

Taking on the job is going to mean more than flying up to Georgia to look at the crime scenes and watch the victims’ home movies. Graham is also going to have to make a stop in Baltimore to visit an old enemy of his. Locked in a maximum-security cell at a mental hospital in that city is a psychiatrist named Dr. Hannibal Lecktor (Brian Cox, later of Kiss the Girls and The Ring), the last psychopath Graham caught and the man who nearly killed him. Having been out of the loop so long, Graham believes he is no longer in touch with whatever part of his mind allowed him to think like a dangerous lunatic, and he figures a little talk with Lecktor (by the way— note the change in spelling) is exactly what he needs to reset his mental intonation, as it were. True, the last time Graham tried to attune his mind to the mad doctor’s, he nearly went insane himself, but with who knows how many lives at stake, that’s a risk William is willing to take. Besides, Lecktor is still a brilliant psychiatrist, and he might have a useful insight or two into the personality of Graham’s current quarry. Of course, as we all know from the more famous subsequent films to feature the character, Dr. Lecktor is at least as interested in playing head-games with the police as he is in helping them, and Graham comes away with more riddles than answers. And it can’t be good news for our hero when Lecktor later tricks his way into making a phone call to the psychologist attached to Crawford’s unit, and finagles Graham’s home address out of an off-hours receptionist.

Lecktor and “the Tooth Fairy” (as the FBI agents on the case have taken to calling their unknown, corpse-biting nemesis) aren’t Graham’s only problems, either. There’s also a reporter from the National Tattler, a man named Freddy Lounds (Stephen Lang), who had covered Graham’s pursuit of Lecktor, and who has just begun making a pest of himself once again. However, it may just be that in this case, Lounds could be of some real use. One of the orderlies at the hospital where Lecktor is confined uncovers a note in the doctor’s cell which appears to have been sent to him by the Tooth Fairy. Part of the note is missing, but it looks like an attempt by the two psychos to set up a system of communication through the personal ads page of the Tattler. Graham’s first idea is to intercept Lecktor’s ad, and substitute one of his own devising which will lead the Tooth Fairy into a trap. But when the Tattler editors find the ad the FBI is looking for, it proves to be in code; reasoning that the Tooth Fairy has already been prepped to look for a coded message, Graham and Crawford reluctantly agree to let the ad run as-is, and instead use Lounds to provoke the killer into coming after Graham himself. Graham gives Lounds his story, but he fills it with false information calculated to enrage the deranged murderer, and arranges for it to run accompanied by a photograph that will tell the killer exactly where to come looking for him. Unfortunately for Graham— and for Lounds even more so— the Tooth Fairy comes looking for the reporter instead. He abducts Lounds in a parking garage, has him read a prepared message for the FBI into a tape recorder, and then rolls him back down the ramp into the garage whence he was shanghaied in a wheelchair after tying him up and setting him on fire. What’s more, when Crawford’s cryptography men succeed in decoding the message from Lecktor which just ran in this week’s Tattler, it turns out to be the Graham family’s home address, together with the exhortation, “Kill them all and save yourself.”

Meanwhile, somewhere in Missouri, we are introduced to a photography lab technician by the name of Francis Dolarhyde (Tom Noonan, from Wolfen and RoboCop 2). Like the killer, he’s a big man— six feet, seven inches tall; 217 pounds— with longish, blonde hair. More significantly, his house is also a dead ringer for the place where we just saw the Tooth Fairy take Lounds. Dolarhyde is just beginning a romance with a blind coworker named Reba McClane (Face/Off’s Joan Allen), and the following scenes will present us with a fascinating juxtaposition, as Graham immerses himself ever deeper in what he hopes is the Tooth Fairy’s mindset, even as the killer himself strives after one last chance to build a normal, non-murderous life around his relationship with Reba. It doesn’t last long, though. Dolarhyde sees Reba with another man just as the lunar cycle that governs his madness comes around once again, while back in Atlanta, Graham makes an intuitive leap based upon a hitherto unnoticed detail of the victims’ home movies that will lead him and Crawford straight to Dolarhyde.

You’ll notice that the above synopsis says relatively little about Hannibal Lecktor. Truth be told, I have, if anything, exaggerated his importance in Manhunter. The character has only two scenes, and his only real function is to raise the stakes by telling Dolarhyde how to find Will Graham. The film never even bothers to mention his now-notorious cannibalism. In keeping with the extremely limited nature of his role, Brian Cox gives a far more restrained performance in the part than Anthony Hopkins would five years later. Rather than an almost fantastic human monster, fascinating and repellant in equal measure, Cox’s Lecktor is just a soft-spoken man in prison coveralls. Indeed, he comes across as slightly pathetic— witness the desperate way in which he backtracks when Graham fools him into thinking that his feigned lack of interest in the Tooth Fairy case is about to cost him an opportunity for attention and amusement outside of his normal routine at the asylum. Really, with Cox in the role, it’s just as well that Manhunter spends as little time on Lecktor as it does.

Michael Mann, the director of Manhunter, was also the brains behind The Keep. And while Manhunter is far more successful than the earlier film, there is a strong family resemblance. Both are chilly, stylized, and ultimately superficial movies, visibly unconcerned with what makes any of their characters tick. The romance between Dolarhyde and Reba is almost as rushed and strains credulity to nearly the same extent as that which develops between the professor’s daughter and the avenging angel in The Keep, the nature of the mental tic that makes Graham such a good detective and the price that he pays for exploiting it are not explained until the movie is half-over, and again Mann makes next to no effort even to ensure that we know all the characters’ names. The director’s anti-exposition bias shows once more, in that there are a handful of scenes which make absolutely no sense at all unless you’ve read the book, because the context that explains them has been left by the wayside, apparently for fear of slowing the movie down. Mann also continues to display his long-established love for somewhat overwrought lighting effects, and while the rather obtrusive electronic score was neither written nor performed by Tangerine Dream, it certainly could have been.

The reason Manhunter mostly works anyway, I think, is that unlike The Keep, it takes place entirely in the real world. It doesn’t matter as much that Mann hates taking the time for exposition, because far less exposition is necessary for us to have some idea what’s going on. We already know what the FBI is, we have some background experience with psychopathic serial killers, and in general, there’s very little to the story that couldn’t turn up one day as a segment on “America’s Most Wanted.” So even if Mann never gives us enough information to be certain of why most of the characters are doing things, we still have a strong instinctive understanding of what they’re doing. Matters are further helped by the quality of the performances. All the roles are underwritten, but one gets the sense that the actors were privy to certain information about their characters’ motives that Mann did not see fit to entrust to us. Because William Petersen, for example, appears to know what’s going on inside Will Graham’s skull, it becomes a little bit easier to accept on faith that his actions would make perfect sense if somebody were to let us in on the secret. The only characters who remain totally inscrutable are Dolarhyde and Lecktor, and since they’re both insane anyway, maybe that’s to the good.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact