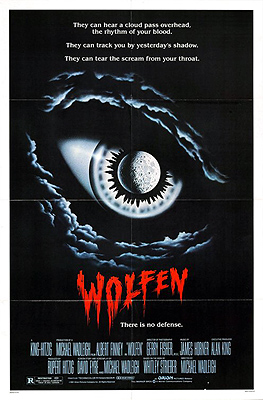

Wolfen (1981) ***

Wolfen (1981) ***

1981 was a big year for werewolf movies— maybe not so much in raw numbers, but certainly in terms of impact. The Howling and An American Werewolf in London between them permanently reset what audiences would expect of cinematic lycanthropy, and they were among the most conspicuously promoted movies of the year. No doubt my own tastes in film biased me in favor of noticing them, but the advertising push from their respective distributors was pretty hard to miss. And then there was Wolfen. Arriving in company with those other two pictures, anything with that title would naturally be taken for more of the same, and while none of Wolfen’s trailers, commercials, or print ads ever came out and said “werewolf,” they certainly did nothing to counteract the assumption. The only people who might have caught on that something more unusual was in the offing were those who had already read Whitley Strieber’s novel of approximately the same name. Strieber’s The Wolfen was about werewolves only in a roundabout way. It posited that werewolf legends the world over arose from pre-modern people’s attempts to make sense of humankind’s last true predator, a species of canid with an intellect comparable to our own, and a culture that prioritized keeping its very existence secret from the prey, which had grown too dangerous in recent centuries to hunt openly. But Michael Wadleigh’s film adaptation is something even stranger than that, and much harder to explain. Although Wadleigh retains the core premise of a canid species with hominid intelligence, lurking in the shadows of man’s increasingly blighted cities, he has transformed what was originally just a clever knockoff of Peter Benchley’s Jaws into a wide-ranging, multi-layered meditation on turn-of-the-80’s urban malaise. It isn’t altogether coherent, and it probably wouldn’t be even if we could see the commercially impossible four-and-a-half hour rough cut that was Wadleigh’s last contribution before the Orion Pictures bosses took control of the project away from him, but Wolfen is well worth a look anyway.

Sleazy Manhattan real estate developer Christopher van der Veer (Max M. Brown) is out on the town with his wife, Pauline (Anne Marie Pohtamo), celebrating the biggest business coup to come his way in years. His firm has gobbled up the land beneath one of the most uninhabitable ex-neighborhoods in Brooklyn with an eye toward rebuilding it into a clutch of hyper-luxury high-rise apartment towers, and the first squadron of bulldozers is assembling even now to begin razing the condemned ruins in preparation for groundbreaking. Van der Veer, feeling dynastic, has his chauffeur-bodyguard (Jaws of Satan’s John McCurry, who was one of the American actors edited into Gammera the Invincible) head over to the Battery, where Christopher’s most illustrious ancestor set up the first windmill in New Amsterdam over 250 years before. While the couple stroll about the park commemorating that historic establishment, neither they nor their watchful retainer realize that they’re being stalked. We don’t get to see what’s doing the stalking, but the point-of-view shots representing their presence indicate an eye level about three feet off the ground and a range of optical frequency response extending significantly into the infrared band. (Wolfen’s publicists were justly very proud of this effect, and made sure it figured prominently in all the trailers and TV spots. Today, of course, thermographic imaging is a standard technique for showing when someone is being observed by inhuman eyes, but this was the first movie ever to use it that way.) When the strike comes, it happens so fast that the chauffeur loses his hand before he can finish drawing his pistol. And in the morning, when the bodies are discovered, they’re in such a state as to challenge the descriptive ability of the police dispatcher.

Warren (Dick O’Neill, from The U.F.O. Incident and Chiller), the NYPD’s chief of detectives, is so appalled by what he finds on the scene that he un-suspends his most talented but least reliable man to lead the investigation. If you can imagine Columbo after a bad divorce and a year and a half at the bottom of a bottle of Old Crow, you’ll have a pretty clear picture of Detective Dewey Wilson (Albert Finney, of Night Must Fall and Looker). Even in all the decades that grizzled old grouch has spent on the homicide squad, though, he’s never seen anything like this. Disembowelment, disfigurement, dismemberment, the works. The perps even opened up the victims’ skulls, and took the fucking brains! It would take a real psycho to do a thing like that— unless maybe the murder was some kind of warped religious ritual instead? What gets Wilson thinking along those lines is the ring on the chauffeur’s severed hand, which identifies him as a Vodouisant. Perhaps he (or van der Veer, for that matter) pissed off the wrong bokor? Chief Medical Examiner Whittington (Eve of Destruction’s Gregory Hines) has even more puzzling news for Wilson after he’s finished his autopsy. Whatever made those wounds was harder than bone, but non-metallic. The act of sharpening a blade covers it with microscopic metal shavings, you see, some of which inevitably get transferred to anything it’s used to cut. Those always show up on an X-ray, but none are visible in the ones that Whittington took. Also, there were non-human hairs on the bodies, and while they don’t match any of the fiber samples in the ME’s files, the species to which they’re least dissimilar is a dog.

Dewey Wilson’s isn’t the only investigation into van der Veer’s murder, however. The dead man was a client of a private security firm, and Executive Security has detectives of its own. Wilson’s counterpart at the company is a man called Ross (Peter Michael Goetz, of King Kong Lives and C.H.U.D.), and he’s proceeding on the theory that van der Veer fell victim to political assassination. It would make sense, since the family is implicated in colonial malfeasance, both past and present, on every continent save Antarctica. Also, it just so happens that the Haitian bodyguard was also a former member of the Tonton Macoute, so even Wilson’s Voodoo vengeance theory is susceptible to a geopolitical reading. In any case, Ross thinks the effort to crack the case would benefit from the services of an expert on terrorism and underground radical movements, so he calls in Dr. Rebecca Neff (The 13th Warrior’s Diane Venora) to assist him. But when Neff’s first seemingly promising lead— a trust-fund anarchist distantly related to van der Veer, by the name of Cicely Rensselaer (Sarah Felder)— comes up bust, she decides to join forces with Wilson instead. (Incidentally, I’m almost certain that we’re meant to read Cicely as a descendant of those Rensselaers.)

Meanwhile, the dead tycoon’s demolition crews in Brooklyn discover something extraordinary. In a rubble-strewn lot beside an abandoned church, their labors turn up a horrifying profusion of human body parts. None of the remains are complete enough to be identified as belonging to anybody, but Whittington will later determine that several different individuals are represented, and that every one of the limbs, organs, and whatnot is in some way poisoned or diseased. Wilson suspects a link to the Battery murders (which, after all, involved all manner of amputations and extractions), and races to the scene with Neff in tow as soon as he hears the news. Doing so provides the pair with the strangest and most alarming clue yet, because something chases them out of that church after trying unsuccessfully to lead them into an ambush. Neither investigator gets a good look at their attacker while running for their lives, but it’s big, fast as fuck, and definitely not human.

That narrow escape gets Wilson and Neff thinking about the seemingly canine hairs taken from the bodies in the Battery, and they call in an expert of their own. A biologist named Ferguson (Tom Noonan, from Last Phases and Manhunter) at the Museum of Natural History informs them that the hairs came not from a dog, but from a wolf. That’s weird enough, but what’s weirder still is that the wolf in question didn’t belong to any of the several known species. It must be a hybrid or a mutant or something. And that revelation triggers in Wilson a truly uncanny thought for a man in his business. While Neff was hounding Cicely Rensselaer, Wilson was checking out possible political angles, too, by paying a visit to an old nemesis of his. Native American radical Eddie Holt (Edward James Olmos, of Black Fist and Blade Runner) seemed at the time to be just as dead an end as the Rensselaer girl, but with this new talk about hybrid wolves, Wilson remembers him making the bizarre boast that he could “shape-shift with the best of them.” The detective dismissed it as either superstitious Indian nonsense, or devious nonsense designed to exploit white people’s superstitions about Indians, but now… Granted, it’s impossible. It has to be impossible, right? But Wilson would have said the same about the thing that came at him and Neff in the church if you’d asked him the day before yesterday. So maybe Holt and his militant pals are worth a second look, albeit from a very different perspective.

Alas, shape-shifting turns out to have a much more prosaic meaning in this case than the literal one, and Wilson once again finds himself barking up the wrong tree with Holt. Even so, he’s a lot closer to the answer than Ross is, chasing after a second nest of wannabe Weathermen who call themselves Gotterdammerung. Closer still, though, is Ferguson, who simply takes it at face value that he’s on the verge of discovering a hitherto unknown species of super-wolf, living against all odds in the heart of New York and somehow preying unnoticed on what is otherwise the Earth’s unquestionably dominant animal. That said, not even Ferguson has thought yet to ask the most important question of all: if these mutants or werewolves or whatever live in the bombed-out Brooklyn slum that van der Veer’s company is fixing to raze, then what the fuck were they doing all the way over in the Battery on the night when they killed the developer, his wife, and their bodyguard?

I want to draw your attention back to the length of Michael Wadleigh’s rough cut of Wolfen. The version ultimately released to theaters runs one hour and 54 minutes, meaning that Orion left roughly two and a half hours of footage on the cutting room floor. So if Wolfen leaves you with the sensation that something must have gone missing somewhere, it really, really did! What’s surprising, though, is that the studio snippers seem to have been no less eager to remove essential, premise-establishing material carried over from the book than they were to prune back Wadleigh’s wilder flights of sociopolitical fancy. Wolfen in its final form therefore presents the rare challenge of a film that you’ll be hard-pressed to understand unless you’ve read a novel to which it bears only the crudest resemblance.

That said, I harbor a considerable amount of goodwill for this bizarre and bewildering movie. In some ways, I even consider it an improvement on the source material, although I certainly wouldn’t say that across the board. Wadleigh may have steadfastly refused to engage with Strieber’s best ideas, but I’m not sure how he could have made much use of them, anyway, in a visual medium like film. In The Wolfen, the “werewolves” were viewpoint characters, and their perspective increased in importance as the story progressed. Those nifty thermographic POV shots are as close as the movie ever comes to that. It’s one thing, however, to depict alien eyesight, and something else again to depict an alien mindset. Wadleigh could not, as a practical matter, show us how the creatures think, how they communicate, how they relate to a world that they experience primarily through the sense of smell, and it was probably smarter not to try. And it was definitely smart to reset the relationship between Wilson and Neff on terms that almost automatically precluded the hackneyed and annoying “battle of the sexes” stuff that wasted page after page in Strieber’s telling.

But the main thing is that Wadleigh’s Wolfen is just a lot more ambitious than Strieber’s, even if most of its ambitions were hobbled in the end by injudicious editing at the behest of people who neither understood nor cared about them. One of the novel’s more movie-ready points was that the Wolfen do to humans what every other mammalian predator does to its preferred prey species, culling the unfit— the weak, the old, the sick, the disabled. But humans do something that prey species like wildebeests, mountain goats, and antelope typically don’t. We organize our societies so as to create the unfit in mass quantities, then abandon them to fend for themselves against every sort of hardship. That difference is the fulcrum on which Wadleigh’s Wolfen turns, in ways that Strieber never took up at all. Sure, humanity’s unique callousness explains how the super-wolves are able to keep hidden even in densely populated cities, because the rulers of those cities don’t give a shit whether large numbers of their subjects live or die. But it also represents an unexpected new dimension in portraying civilization as defying the natural order, going beyond all the usual concerns about despoiling the physical environment.

The trouble with this elaboration of the original concept, of course, is that it’s difficult for the Wolfen to be both an embodiment of the familiar “urban jungle” metaphor and the centerpiece of an argument that the metaphor gets it exactly backwards. Then Wadleigh muddies the waters further by running off on all sorts of tangents from the central idea. Eddie Holt and his Mohawk radicals are philosophically opposed to urbanism and everything that goes along with it, yet have ironic day jobs literally building the city as “skywalking” construction workers. They also serve, at various points in the story, both as plausible scapegoats for the Wolfen’s depredations, and as the source of what little real understanding of the creatures Wilson will ever acquire. Ross and his company, meanwhile, underscore the theme of elite disregard for the underclass with their unshakable fixation on terrorists as the culprits in the van der Veer slaying. They’re incapable of imagining the truth of what happened because they can’t accept the fates of junkies and bums being relevant to a tycoon’s death, no matter how similar the circumstances of the killings might be. But then again, Ross is right in one sense, because the Wolfen really did target van der Veer for assassination. He threatened the habitat of the one non-human species on Earth that might be capable of doing something about it. So basically, there’s a lot going on in Wolfen, and that conceptual density is both its greatest strength and its greatest weakness.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact