Dragonwyck (1946) ***

Dragonwyck (1946) ***

One thing you see very clearly in gothic fiction as it separated into parallel horror, mystery, and romance strains is a shift in how the emergent subgenres approached the supernatural. As the ghoulies and ghosties and long-leggedy beasties and things that go bump in the night grew increasingly important in gothic horror, especially during the 19th century, gothic mystery and gothic romance made correspondingly less use of them. By the 1930’s and 1940’s, when gothic romance was entering the final phase of its mainstream popularity, it was rare to encounter even a fake haunting anymore. The heroine’s love interest would still be a Byronic creep, and his ancestral manse would still be a venue of dread and spiritual danger, but whatever evil lay in wait for the heroine there could safely be assumed human in nature. So you might expect a gothic novel by an author who considered herself strictly a writer of historical fiction to include no trace whatsoever of the supernatural— not even a metaphorical ghost like the dead woman whose memory looms so heavily over the characters in Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca. And you might think that would go double for one devoted largely to a fictionalized examination of the issues underlying a criminally underexposed chapter in American history, the 1840’s Hudson Valley Rent War. However, not only does Anya Seton’s Dragonwyck have a ghost, but the movie adapted from it by Joseph L. Mankiewicz has probably the second-creepiest ghost of the whole 1940’s! It’s a minor part of the film, to be sure, but that ghost is the first and clearest indicator of how hard Mankiewicz plans on hitting the “gothic” part of gothic romance here.

I suppose I should start with a quick recap of the Hudson Valley Rent War, shouldn’t I? Remember that New York was originally colonized not by the British, but by the Dutch. In 1630, the Dutch West India Company sought to encourage the settlement of the Netherlands’ new territory on the North American mainland by offering its members an opportunity that could no longer be had in most of Europe. In the lands under its jurisdiction, it established a fully feudal land-tenure regime in which the proprietors— called “patroons”— would hold all ownership rights, and the tenant colonists would be bound by oath and held liable for rent in the form of both agricultural produce and a fixed number of days’ unpaid labor in the patroon’s own fields. The tenants lacked even the right to travel outside the patroonship’s borders without the written permission of their landlord. When the British finalized their takeover of New York in 1686, the government kept the West India Company’s system in place for the sake of smoothing the transition and keeping the peace. It survived the establishment of the United States of America, too, thanks to the patroon class’s support during the revolution. (Crown and Parliament finally tried to bring the patroons to heel in 1775, which naturally drove them into the revolutionary camp.) Nevertheless, a bubble of feudalism could comfortably exist for only so long within a country that prided itself (justly or not) only liberty, and by the 1830’s, tensions between tenants and landlords were running high all along the Hudson Valley, where the majority of the patroonships were located. The irony is that when the crisis came, it was due in part to one of the exploiters giving the exploited a break.

The largest of the patroonships was the Manor of Rensellaerswyck. Since 1785, it had been controlled by Stephen Van Rensellaer III, remembered by local history as “the Good Patroon.” No doubt his lax attitude toward collecting the rent owed him by his tenants had something to do with that moniker— and as the tenth-richest man in the United States, he could well afford such leniency. But when Stephen died in 1839, his will mandated that the back rent be paid to his heirs, so that they might not be burdened by the considerable debts he had accumulated. The total arrears came to some $400,000, an astronomical sum of money in those days, and one that the tenants of Rensellaerswyck could not plausibly be expected to cough up. Stephen IV, who inherited the western half of the manor, made matters worse with his high-handed attitude toward the committee assembled to represent the farmers on his estate, and in the summer of 1839, the tenants rose in open revolt. They withheld their rents, they ignored their landlord’s writs of eviction, and they chased off the 500-man posse set upon them by the sheriff of Albany County. The rent strike persisted even when Governor William H. Seward sent a company of state militiamen to occupy Rensellaerswyck. By 1844, resistance to feudal rents had spread all up and down the Hudson Valley. The situation devolved into a state of genuine guerilla warfare, with rebel mobs disguised as Indians attacking agents of the patroons wherever they showed their faces and a further three companies of militiamen mobilized in the hope of restoring order. Delaware County was officially declared a site of insurrection after an anti-renter infiltrated an eviction sale to assassinate Undersheriff Osman Steele.

The anti-renters weren’t just rebels, though; they also pursued legally sanctioned forms of resistance. They published a newspaper, formed lobbying groups to put pressure on town, county, and state government, and ultimately organized a fully fledged political party. Those efforts were so successful that a rule against creating new patroonships (like Stephen III had done by dividing Rensellaerswyck between his two sons) was written into the revised New York State Constitution of 1846, and for the next five years, the Anti-Rent Party was the decisive force in New York politics, skillfully playing the much larger Democratic and Whig Parties against each other. Although the New York Court of Appeals ultimately ruled that the existing patroonships could not legally be broken up, the anti-renters made things so hot for the patroons that by 1851, virtually all of them had sold out and relinquished their former rights by the terms of the new constitution.

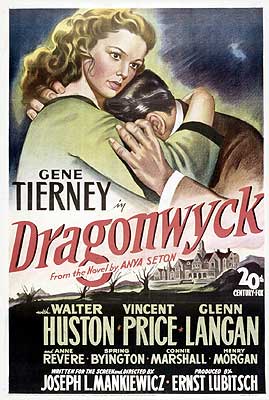

You’ll know the meaning of the date, then, when Dragonwyck begins with a caption identifying the setting for the first scene as “A road near Greenwich, Connecticut, May 1844.” Skipping down that road toward home is teenaged Miranda Wells (Leave Her to Heaven’s Gene Tierney), eldest daughter of stereotypically dour Yankee farm couple Ephraim (Walter Huston, from All that Money Can Buy and Transatlantic Tunnel) and Abigail (Anne Revere, of The Devil Commands). The Wellses have just received a curious letter from a New Yorker named Nicholas Van Ryn, who claims to be a cousin of some sort. Van Ryn says he’s seeking a girl to come live at Dragonwyck, his home in the Hudson Valley, to serve as a companion to his daughter, Katrine. If you’re wondering how this bunch could possibly have a patroon for a cousin, look to Abigail’s grandmother, who was Nicholas’s grandmother first. Having made it to the top of the social ladder with her first marriage, the old gal evidently dived right off of the thing with her second. Anyway, the moment Miranda learns the contents of the letter, she gets a faraway look in her eyes, fantasizing about a lifestyle that she barely knows how to imagine. Ephraim is disinclined even to consider the idea of sending Miranda to Dragonwyck when he comes home from the fields, but a bibliomancy check made at the girl’s insistence turns up Genesis 21:14: “And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and took bread, and a bottle of water, and gave it unto Hagar, putting it on her shoulder, and the child, and sent her away: and she departed, and wandered in the wilderness of Beersheba.” Not one to argue with God, Ephraim grudgingly consents to the arrangement— assuming, of course, that Van Ryn doesn’t turn out to be a libertine or a sodomite or worse yet, a Catholic.

Actually, Nicholas Van Ryn turns out to be Vincent Prince, which is probably the most ominous possibility of all. Then again, this was only 1946, so Dragonwyck’s original audiences might not have leapt instantly to the same conclusions as we do today. Ephraim remains skeptical just the same— the mere fact that Van Ryn sets their rendezvous point at a posh hotel in that modern-day Gomorrah, Manhattan, sets his teeth on edge all by itself— but in the end, he’s forced to concede that his only grounds for objection are his own class and regional prejudices. For her part, Miranda is swept off her feet by her cousin’s suave manners, elegant appearance, and effortless sophistication. In fact, it’s almost as if she missed the part about him being married and having an eight-year-old child.

However smitten Miranda may be with Nicholas, though, Dragonwyck is not at all what she expected. Sure, the place looks gorgeous from the deck of a riverboat on the Hudson, but on the inside, it’s gloomy and chilly and grim. Nicholas’s wife, Johanna (Supernatural’s Vivienne Osborne), is as unappealing as she is unhappy, emotionally distant and seemingly uninterested in anything except stuffing her fat face with expensive pastries. Katrine (Connie Marshall, of The Twonky), the little girl whose company Miranda is supposed to keep, is even more withdrawn, convinced that her parents don’t love her and feeling nothing for them in return. Magda the housekeeper (Spring Byington, from Werewolf of London and The Rocket Man) has at least a brown belt in servile passive aggression, and lets Miranda know in no uncertain terms that she considers the girl an intruder and an imposter at Dragonwyck. And on top of everything, the house is rumored to be haunted by the spirit of Nicholas’s great-grandmother, Adele, who committed suicide to escape a loveless marriage soon after the birth of her son. Supposedly Adele plays her beloved old harpsichord in celebration whenever misfortune is about to befall the Van Ryn family, but only her blood kin can hear the spectral music.

Great-Grandma Adele isn’t the only one who has it in for the Van Ryns, either. Dragonwyck is caught up in the Hudson Valley Rent War just like all the other patroonsips. The anti-renters have no shortage of representatives around here, but their most eloquent local spokesman is Dr. Jeff Turner (Glenn Langan, from Women of the Prehistoric Planet and The Amazing Colossal Man). Miranda meets him and is introduced to the whole rent issue when she attends the annual harvest festival at which the tenant farmers are supposed to hand over the appointed share of their produce. The rent ceremony almost descends into riot thanks to the truculence of Klaas Bleecker (Harry Morgan, of Maneaters Are Loose!), who very publicly refuses to hand over a dime to his landlord. Nicholas doesn’t exactly cover himself with glory on this occasion, either, taking a nasty, patronizing tone with Bleecker and the other farmers. Miranda notices, but she doesn’t seem to process the implications of what she sees at the festival.

Another development with implications that elude Miranda at the time is the wasting illness that comes over Johanna. Let me lay out the dots, and see if you can connect them any better. (1). Although Miranda is officially at Dragonwyck to keep Katrine company, she actually spends most of her time with Nicholas. (2). Conversely, Nicholas seems to be spending as little time around his wife as he can manage. (3). About the one act of kindness that we see Nicholas perform toward Johanna is to move her favorite houseplant into her bedroom from wherever it had lived previously. (4). Said houseplant is an oleander, a species which produces such a vast pharmacopoeia of toxins that no part of it can be safely injested— not even fragments of dead, dry leaves. (5). When Johanna’s condition first takes a turn for the life-threatening, Katrine is awakened in the middle of the night by the sound of a harpsichord playing, but Miranda can’t hear anything, even when the child complains that the music has grown both frighteningly wild and deafeningly loud. Johanna dies soon thereafter, even despite a visit from Dr. Turner, and Miranda goes home on the theory that houseguests and mourning don’t mix.

Like I said, though, Miranda doesn’t see the pattern yet. The girl can’t get Dragonwyck out of her head, to say nothing of Nicholas Van Ryn. Nicholas has been just as fixated on her, too, since she returned to Greenwich, and once a socially acceptable interval has passed, he shows up on the Wells doorstep with a proposal of marriage. Ephraim tries to butt in again, but Miranda isn’t having it. She’d like nothing better than to be the new Mrs. Van Ryn, no matter what her surly old dad thinks. However, as I’m sure you already suspect, our heroine will soon have cause to think more critically about the timing, course, and cause of Johanna’s sickness. For that matter, she’ll also have cause to think a lot more about the legend of Great-Grandma Adele, since her experience of marrying into the Van Ryn clan is going to resemble the phantom lady’s a lot more closely than she’d like.

The film version of Dragonwyck largely owes its existence to the overwhelming popularity of Rebecca, which initiated a short-lived but intense vogue for gothic romance movies. It’s therefore more than tempting to look at Dragonwyck in reference to the earlier picture. Although I’ve rated them the same, and consider them more or less equal on the balance, the specific things Dragonwyck gets right are such that I enjoyed watching it significantly more. The main reason relates to a problem I’ve often had in appreciating movies of this vintage: I simply can’t understand how 1940’s Hollywood got it into its collective head that the most appealing combination for a love story was a male jerk and a female dullard. You see it so often, though, that I can only assume it must have spoken to people at the time, and its prevalence in pop culture can’t help but have influenced their expectations of how romantic relationships were supposed to work. Rebecca is, among other things, the all-time classic of the Jerk+Dullard formula. Dragonwyck leaves the presumably ticket-selling contours of that formula in place, but commendably subverts it at every turn.

Nicholas Van Ryn is certainly jerk enough, and his marriage to Miranda is almost entirely the product of her naivety and wishful thinking. But Miranda eventually catches on in a way that the second Mrs. De Winter never really does. Once that happens, she becomes a handful and a half for her reprobate husband, standing up for herself with all the moxie her spiritual sisters lack. It’s a little thing, but also the most telling of the difference between Miranda and the typical 40’s Hollywood heroine: notice that Magda is never seen again at Dragonwyck after Miranda and Nicholas are married. Mrs. Danvers would’ve been on the Dole line the moment she first tried her patented blend of bullshit on this girl! Also, it’s worth pointing out that the one person whom Nicholas never mistreats during Miranda’s initial stay at Dragonwyck is Miranda herself. That’s a crucial contradistinction versus Rebecca’s Maxim De Winter and others of his ilk, who are reliably as shitty to their love interests as they are to everyone else. Given all the worshipful attention Nicholas lavishes on her prior to their marriage, it’s easy to see how Miranda could overlook her cousin’s contemptuous exasperation with Johanna, his callous neglect of Katrine, and his imperious cruelty toward his tenants.

Speaking of the Dragonwyck tenants, what most stands about this movie is its overtly political handling of that old gothic standby, aristocratic decadence. The Hudson Valley Rent War is Dragonwyck’s answer to the crack in the foundation of the House of Usher. Throughout the film, the course of the conflict serves as a symbolic benchmark for Van Ryn’s descent into madness and evil. The closer the anti-renters get to overthrowing the system of patroonship, the more depraved Nicholas becomes. Miranda’s disenchantment with her cousin-turned-husband has a political dimension, too, for the decisive factor is Peggy O’Malley (Jessica Tandy, from The Birds and Cocoon), the crippled Irish halfwit whom she hires to be her handmaid. Miranda takes Peggy in both as an act of Christian charity and as a Yankee incitement to self-betterment by hard work, but Nicholas is horrified at the prospect of sharing his home with so defective a specimen of humanity. His disgust with Peggy’s disability is what fully opens Miranda’s eyes to his true nature. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that a film made roughly a year after the liberation of Auschwitz would have its socially and politically powerful villain express such sentiments, or that the same villain would also espouse a specifically Nietzschean form of atheism in which the nonexistence of God implies the unreality of morals. Nazis and their sympathizers had been the go-to baddies of so many other genres for five or six years, why not slip one into a gothic romance, too? But there’s also more going on here, I think, than Hollywood just having Hitler on the brain. I think Mankiewicz was deliberately pointing out an essential parallel between Nazism and feudalism— and indeed between either of them and practically any system of oppression. They all start with the premise that some people are just better than others, and that the inferior masses have no rights that the nobility, the Herrenvolk, the Übermenschen need respect. To draw that point out and then to situate it in an American historical context was pretty nervy of Dragonwyck’s creators. And it sure as hell wasn’t something I ever expected to see in a mid-40’s gothic romance!

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable on haunted, cursed, possessed, or otherwise evil locations. Click the link below to tour the rest of this neighborhood of the damned.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact