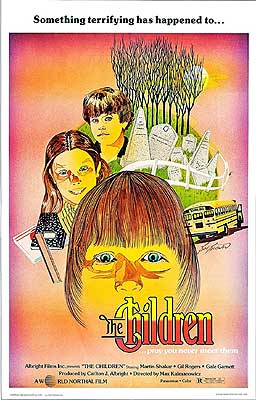

The Children / The Children of Ravensback (1980) ***

The Children / The Children of Ravensback (1980) ***

Up until Chernobyl permanently recalibrated the scale for nuclear power plant disasters, the first and last words in atomic reactor fuck-ups were “Three Mile Island.” The twin-reactor plant of that name, located near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, suffered a coolant leak in March of 1979, leading to a partial core meltdown. In addition to the coolant spill (amounting to some 32,000 gallons), a hydrogen explosion in the housing of the number-two reactor combined with deliberate venting intended to forestall a much larger and potentially catastrophic explosion to release great volumes of contaminated steam and iodine vapor into the atmosphere around and above the plant. The cleanup of the site wasn’t deemed complete until 1993, and the incident provoked a major tightening of regulations governing the design, construction, and operation of commercial nuclear power facilities. Three Mile Island was deservedly a public relations calamity as well as an environmental one, and the reputation of the atomic power industry in the United States has never entirely recovered, both for better and for worse. So if you’ve ever wondered why the early 1980’s saw such a sudden, sharp spike in stories about the mishandling of nuclear energy and its waste products, look no further. One of the earliest horror movies to reflect the newly widespread anxiety over the Not-So-Friendly Atom was The Children, a crude but nifty killer-kid flick in which the children of a tiny Northeastern town are turned monstrous by an accident at the local nuke plant.

Although the mishap at the Yankee Power Company’s Tier One Nuclear Generating Facility is markedly less serious than the one at Three Mile Island, the details would have been immediately recognizable to those few people who saw The Children during its very limited theatrical run. A malfunction in the coolant system spews a cloud of radioactive gas into the air, where it is borne on the wind toward the nearby village of Ravensback. Although the cloud disperses quickly enough, it arrives just in time to envelop the school bus carrying Ravensback’s children home that afternoon, together with Cathy Freemont (Gale Garrett), who passed the bus in her Volkswagen a moment earlier. Whatever was in that cloud, it apparently has no effect on adults, because Cathy makes it home just fine, and suffers no ill effects later on. The kids on the bus are another story, however. Although it will be a while before this is fully revealed, the gas transforms them into predatorily cunning but otherwise almost mindless zombie-like creatures, capable of shrugging off virtually any injury, and of channeling lethal doses of ionizing radiation through their hands into any living thing they touch. They’re like ambulatory microwave ovens, and although the details of the children’s condition are commendably left vague beyond that, there are unsettling hints that the youngest kids are affected faster than their elders, and that the irradiated tykes are driven, like the vampires in Black Sabbath, to seek out their loved ones in preference to any other victims. They look really happy about what they’ve become, too, which might be the creepiest thing of all. The second-creepiest thing, meanwhile, is that Cathy is pregnant. Everything that happens throughout the rest of the film will have its horror redoubled by the question of what exactly is now developing within her womb.

For now, though, only Sheriff Billy Hart (Gil Rogers, from Luther the Geek and The Panic in Needle Park) has any reason to suspect that anything is seriously amiss. Hart is the one who finds the bus sitting abandoned, with the engine still running, on the road overlooked by Ravensback’s 19th-century cemetery. If the sheriff had climbed the hill to the old boneyard, he would have discovered the poached corpse of Fred the bus driver (Ray Delmolino), and understood at once just how hairy things were about to get in his little community. Instead, though, Hart heads over to the home of Dr. Joyce Gould (The Stepdaughter’s Michelle La Mothe), the next house on Fred’s route. Gould takes an oddly hostile tack with Hart, as does the next neighborhood mom whom he visits, a rich libertine by the name of Dee Dee Shore (Rita Montone, of Bloodsucking Freaks and Maniac). Nevertheless, he at least establishes that neither woman has seen her youngsters* since school let out, nor remembers the bus going by. Starting to fear some kind of mass abduction, Hart interrupts Deputy Harry Timmons (Tracy Griswold) in the middle of trying to bang Suzie MacKenzie (The Prowler’s Joy Glaccum), Ravensback’s most sought-after teen floozy, and sends him to set up a roadblock where the one route leading out of the village intersects the state highway. Then, just to be on the safe side, he deputizes two redneck layabouts called Hank (Edward Terry, who was also one of The Children’s screenwriters) and Frank (Peter Maloney, from Thinner and The Thing) to back Timmons up, and enlists Molly from the general store (Shannon Bolin) to keep her eyes, ears, and CB radio open for anything out of the ordinary.

Meanwhile, the missing kids are wreaking radioactive havoc all over town, seeming always to leave an area immediately before the perplexed and beleaguered authorities arrive, or to arrive in one immediately after they leave. Hart’s efforts are joined by those of Cathy Freemont’s husband, John (Martin Shakar, from Blood Bath and The Dark Secret of Harvest Home), easily the most conscientious and responsible of the Ravensback parents. Freemont is along for the ride by the time Hart discovers what the children have left of Timmons, and picks up Dee Dee Shore’s teenaged daughter, Janet (Julie Carrier), just before she fully succumbs to the effects of the toxic gas. The medium-rare deputy and the burning-handed girl combine at last to give Hart some idea what he’s dealing with, but are unfortunately less informative regarding what he and the villagers under his care are supposed to do about it.

Normally when I talk about two or more movies being sister productions, I mean that they were made in tandem by some combination of the kinds of people who get their names on the promo posters: the same studio, the same producers, the same writer and director, etc. The Children, however, was a sister to Friday the 13th in an entirely different and much rarer sense. Composer Harry Manfredini was the only person to work on both films whom anyone not personally involved in their creation is likely to recognize. Rather, what links them is that they were made back to back in the same locale, employing most of the same hands-on personnel in the camera and sound departments. The result is an interesting, nearly subliminal similarity of texture that defies concise description. It’s a question of the literal, physical touch on the cameras, microphones, and other equipment— the acceleration of a pan, the altitude of a boom, and so on. Friday the 13th is deservedly not a movie famed for the technical virtuosity of its picture or sound, and The Children wouldn’t be, either, even if it were a great deal less obscure than it is. But for a certain subset of horror fandom, this film’s rough-edged appearance and sound quality will seem strangely cozy and comfortable, and all those unsung focus-pullers, key grips, and recordists are the reason why.

That “not quite ready for the big leagues” standard of fit and finish works both for and against The Children, occasionally in surprising ways. So, for that matter, does the film’s awkwardness in more purely creative areas. As often happens in this stratum of the movie business, The Children’s technical weaknesses give it a strange edge of verisimilitude, of the kind that modern “found footage” horror films aspire to, but rarely achieve. Ravensback has a lived-in reality to it, which is heightened by the movie’s rather amorphous structure. What with all the running back and forth after false leads and cold trails, we get to know the town, its people, and the rhythm of their lives to a degree that would be difficult for a more efficiently plotted picture to match, and that in turn makes it easy to become invested in the wellbeing of even very minor figures. Director Max Kalmanowicz, together with writers Carlton J. Albright and Edward Terry, does a clumsy job of it, to be sure, but The Children exemplifies the value to be gained from just hanging out with different groups of characters instead of constantly keeping the camera where the action is. My two favorite scenes of that sort actually got cut from the theatrical release, although they were reinstated for the DVD. They concern the waitress at Ravensback’s greasy-spoon café (June Berry, from Natural Enemies and The Nesting), an aging but still sexy divorced mother of two who longs for a romantic connection with Sheriff Hart, and they contribute nothing whatsoever if all you’re interested in is the developing menace of the radioactive kids. We never even get the expected scene of Sally returning home to find that her little darlings aren’t so darling anymore. Under the circumstances, though, we can pretty much take that turn of events as given, so there’s a powerful sense of overhanging tragedy when we do see Sally give up on waiting around for Hart to pick her up from work (which he’d promised to do before Ravensback’s children started roasting their parents alive), and march tearfully off toward her unseen fate, mistakenly believing that she’s been stood up.

Sometimes, though, the trick backfires badly, and an image, a sequence, or even an entire scene comes out looking not plausibly unprofessional, but merely incompetent. And unfortunately, this is most likely to occur during one of the scenes with the monstrous children, a couple of whom are played by kids who can’t even be trusted to walk silently forward with their arms outstretched, disconcerting grins on their faces. Even the best of the bunch can’t be trusted to do much more that that, either, seriously undermining some moments that no doubt read as absolutely chilling on the script page. I’m thinking in particular about what happens when the children come to the Freemont house, and one of them gets the couple’s young son, Clarkie (Jessie Abrams)— who missed out on getting gassed because he was home sick with a cold— to let him in for a game of hide-and-seek. The scene has some bite to it, make no mistake, but it’s nothing compared to the similar incident in Tobe Hooper’s Salem’s Lot, even though it comes to what should be a far more harrowing conclusion.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact