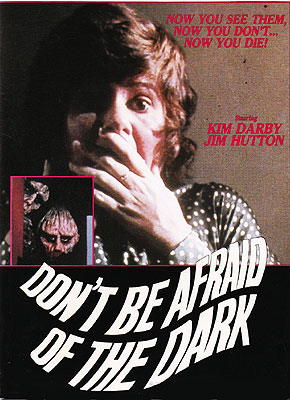

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark (1973) ***

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark (1973) ***

Someday, I’m going to gather together all of the friends I have that would think this a good idea (that is to say, I’ll be doing it alone) for a big “Don’t” movie party. The logistics of this may prove to be a problem, as it’s become a bit hard to find “Don’t” movies of late, but I’m sure it could be done. We would, of course, need Don’t Go In the House, Don’t Answer the Phone, and Don’t Look In the Basement, and if it proved possible, it would be good to have Don’t Go Into the Woods Alone. Fortunately, what may be the most obscure of the “Don’t” movies is also the easiest for me to get my hands on; I actually managed to find the all-but-forgotten Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark just ten minutes away from my house.

I have fond memories of this film. Back in the mid-80’s, it used to air quite often on the USA Network, either on “Saturday Nightmares” or on a similar program that aired during an afternoon timeslot. Those shows were instrumental in laying the groundwork for my graduation from copious consumption of 50’s monster movies and kaiju eiga to the equally copious consumption of more intense 70’s and 80’s gore-horror that characterized my adolescence. It was on “Saturday Nightmares” that I first saw Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell, the last and bloodiest of the Hammer Frankenstein films; Bug, the final opus of the great (well, maybe not quite great...) William Castle; and such rickety 70’s crap-fests as Devil Dog: The Hound of Hell. And as I said, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark seemed to come on an awful lot. In retrospect, that actually makes quite a bit of sense. USA was not one of the premium channels, for which cable subscribers had to pay an extra fee. It was part of Colonial Cablevision’s (and later, Jones Intercable’s) basic package, meaning that it was subject to the same content restrictions as broadcast TV. Since Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark was made for TV in the first place, nothing had to be cut out of it for it to pass FCC muster. The truly amazing thing is that despite its origins as a TV movie, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark is not a gutless piece of shit.

The first thing we see is a huge old house, shot at night as scraps of fog blow by on a high wind. After the credits and the “yup, this is the 70’s alright” opening music have finished, the camera remains trained on the house as a conversation between several high-pitched, evil-sounding voices unfolds in voice-over.

“Is she coming?”

“Yes, very soon.”

“But when?!?!”

“Soon. Then she will set us free.”

“Yes, free! Free in the world!”

Cut then to a series of daylight shots of the same house, accompanied by another voice-over conversation, this one between the new owners of the house, a woman named Sally (Kim Darby, who would later play John Cusack’s mom in Better Off Dead) and her lawyer husband, Alex (Psychic Killer’s John Hutton). The couple is discussing the restoration and renovation of the house, which they inherited from Sally’s grandparents. It’s really pretty amazing how much this one exchange about carpets and paneling and such conveys about the two characters’ personalities. By the time it is over, we will have the impression (which later events will amply confirm) that Alex is an overbearing, self-centered prick with no respect for his wife’s intelligence, and that Sally is exactly the sort of flighty pushover that always seems to gravitate self-destructively toward men like Alex. Subsequent scenes show that the repairs are coming along well and that Sally has at last found the key to a mysterious locked room in the home’s basement. The fact that she had to look for this key should be setting off some sort of alarm in your mind right now. In a movie like this, it never pays to mess around with locked rooms to which the previous tenants hid the keys. What Sally finds when she opens the room only serves to underscore the universal applicability of this principle. The room is a small office of sorts, but it is too poorly lit ever to be useful for that purpose. In fact, all of its windows, and the shutters as well, have been nailed shut. Stranger still is the fireplace, which (as Harris, the old carpenter whom Sally’s grandparents used to employ, and whom Sally has hired for the restoration project, explains) has been bricked over to a quadruple thickness, backed by a steel-reinforced concrete slab, with the access plate to the flue bolted shut for good measure. Harris (William Demarest) knows about the sealing of the fireplace in such detail because he did the work himself, and he strongly suggests that Sally not have the fireplace opened up-- though he is strangely reticent about his reasons, limiting his answer to a cryptic “Some things are just better left alone, that’s all.”

But of course, Sally isn’t satisfied with that-- she wants an office of her own, damn it!-- and one night, she unbolts the hinged metal plate leading to the flue. Having done so, she observes two things. One of these is the phenomenal stoutness of Harris’s brickwork, the removal of which would probably destroy the whole fireplace in the process. The other thing she notices is that the flue seems inordinately deep, as though it extended for thousands of feet into the earth. Now, had you or I made this discovery, we would probably bolt that motherfucker right back up, but not Sally. No, she just leaves it as it is, and goes about her business overseeing the renovations and making the necessary preparations for the big party. Her husband, you see, is angling to be made a full partner at his law firm, and he has invited the partners and their wives, along with several other work-related acquaintances, over to the new house to have their asses kissed by him and his wife.

And that’s when the weird shit starts to happen. First, the key to the basement office vanishes. Then, Sally begins to notice minor acts of poltergeist-like vandalism around the house. Finally, Sally discovers that her dream-house is infested with evil little gremlins about a foot high, who have some kind of designs on her, personally. Alex, as you might imagine, is less than impressed. Like the big fucking dick that he is, he jumps to the conclusion that Sally is deliberately having a nervous breakdown to sabotage his burgeoning career because of the deleterious effect that it has been having on the amount of time he spends with her. Alex tells her to see a psychiatrist, and then hops on a plane for a business trip to San Francisco, leaving Sally to contend with the gremlins alone.

Of course, Alex is eventually convinced that something weird is going on in his house, and that the weirdness is, for some reason, targeting his wife specifically. The turning point comes when the gremlins kill Sally’s interior decorator by tripping him down the main staircase. This happens on the night of Alex’s return from San Francisco, and when he comes home to a house full of police and paramedics, hears that Sally’s friend Joan (Barbara Anderson) believes his wife’s seemingly demented story, and sees for himself corroborating evidence in the form of rope-burns on Sally’s hands (inflicted when she tried to snatch the gremlins’ tripwire away from them), even he can no longer dismiss everything as the product of Sally’s “overactive” imagination. Of course, by then, it may already be too late.

I must admit that Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark has “made for TV” written all over it. You can see it in the small number of sets employed, in the strange air that the scare scenes give off that somehow punches are being pulled, and especially in the “insert commercial here” cliffhanger endings to about a quarter of the scenes. However, for all that, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark actually works pretty well. My overriding reaction to the movie was amazement at some of the things it was able to get away with despite being made under the scrutiny of cowardly television producers (and if you want to try to convince me that there is any other kind, you’re looking at a major investment of time and energy). With the exception of Tobe Hooper’s fantastic Salem’s Lot, this may be the best made-for-TV horror movie I’ve yet seen. Mind you, it is absolutely not in the same league as the latter film, but I’d happily contend that it buries just about anything broadcast TV has done in the horror field in the last fifteen years. If you happened to be blessed with a video store in your area that has a copy of this movie, by all means check it out.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact