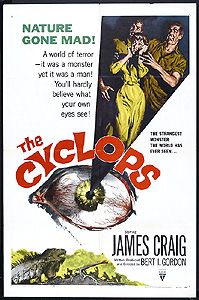

The Cyclops (1956/1957) **½

The Cyclops (1956/1957) **½

I’m honestly not sure I can plausibly defend my shockingly favorable— as in, shocking even to me— opinion of The Cyclops. That’s apt to become rather a problem in just a moment, seeing as making esthetic judgements and then defending them is rather what one does when writing a movie review, and defending the indefensible is the very thing that my readers in particular have come to expect from this site. Also, it obviously isn’t as though I’ve never enjoyed a Bert I. Gordon movie before, so one might justly ask what the problem is. The Cyclops is different, though, precisely because it isn’t different. This was one of Gordon’s earliest films, completed in 1956, but not picked up for distribution until the following year, and like the rest of his work from the 1950’s, it exists primarily to showcase Gordon’s signature embiggening effects— which if anything are even less successful here than they usually were. It’s every inch as cheesy, dumb, and hokey as the better-known movies Gordon subsequently produced and directed for American International Pictures, and nothing that transpires during its 66 pedestrian minutes is half as startling as the sight of the RKO logo in the opening credits. (It speaks volumes for the mismanagement of the Howard Hughes years that that once-proud studio would be reduced in the end to distributing the likes of The Cyclops.) And yet for reasons I despair of articulating, I nevertheless find The Cyclops working for me more often than not— working, that is, in the way Gordon no doubt intended it to work, instead of just as a charming bit of idiocy like Earth vs. the Spider.

Susan Winter (Gloria Talbott, of I Married a Monster from Outer Space and The Leech Woman) is in Mexico again, hunting for her fiance. Bruce Barton has been lost for three years, ever since his little single-engine plane went down somewhere in the Tarahuamare Mountains (not, to the best of my knowledge, an actual mountain range, although the stretch of the Sierra Madre mountains inhabited by the Tarahumara people is sometimes called the Sierra Tarahumara), but Susan remains convinced of his continued survival. One gets the feeling she’s no stranger to the local authorities, either, but this time she’s not settling for any mere assurances that everything possible is being or has been done to locate the missing man. This time, Susan has chartered a plane of her own to retrace Bruce’s flight path, and she’s brought along a search party of her own to help her personally comb the mountains below his last recorded position. The official to whom Susan has applied for the necessary flight permit (The Flame Barrier’s Vicente Padula) frames his reservations solely in terms of mistrust of her companions’ motives, but it looks to me like he also resents the implication that his government’s agents are so lazy, stupid, or otherwise inept that four random gringos can accomplish over the weekend what they could not in three years.

Not that questions of motivation are an empty pretext, mind you— these three really aren’t the obvious crew to assemble for a rescue mission. Lee Brand (Tom Drake, from House of the Black Death and Cycle Psycho) is at least a credentialed pilot, but it seems there may be some uncertainty regarding the current validity of his license back home. The inclusion of a biologist on the team smells awfully fishy until Susan clarifies that Dr. Russ Bradford (James Craig, of The Man They Could Not Hang and Doomsday Machine) is a longtime friend of both her and the missing man. And the participation of millionaire stock speculator Martin Melville (Lon Chaney Jr.) reeks to high heaven even after Susan forthrightly admits that she couldn’t have afforded to mount the expedition with her own resources. It’s a safe bet that Melville didn’t put up the money out of the goodness of his heart, and that he’s envisioning some manner of return on the investment. Maybe he’s thinking of gaming Mexico’s natural resources the way he’s accustomed to gaming the stock exchange? In any case, it’s hard to blame Susan’s contact with the local government when he not only denies her request for a permit to fly over the Tarahuamares, but also insists that she take a police escort with her when she boards Brand’s plane for the trip home— even though that will mean leaving one of her three companions behind to make his own travel arrangements.

That turns out to be a smart precaution, but not half smart enough. Susan indeed has no intention of complying with the official refusal of her rescue mission, and Marty Melville, far from the usual Wall Street stereotype, is plenty rough enough a customer to overpower the cop who meets Susan’s party at the airfield. In practice, the only thing standing between Susan and her fiance’s crash site— or between Melville and the uranium beds he believes for various reasons to be hidden in the Tarahuamares, which are his true reason for coming— is the unpredictable downdrafts that characterize the turbulent air above the mountains. Well, that and the potentially deadly combination of Melville’s utter terror of heights and his millionaire’s assumption that he’s entitled to get anything he wants, right fucking now. When those downdrafts start up, Melville begins frantically demanding that Lee put the plane down, failing to grasp that losing altitude is exactly the wrong thing to do when the wind is gusting straight downward with sufficient force to challenge the power of Lee’s dinky little aircraft. Marty damn near gets everybody killed trying to wrestle the steering yoke away from the pilot, and while Lee does manage to bring the plane back under control, the barren valley where he’s forced to land is steep enough and narrow enough that there’s no guarantee they’ll be able to clear the mountaintops on the way up again.

The good news is that this valley is just about a day’s march from where Susan figures Bruce’s plane crashed, and Melville’s equipment reveals that the place is indeed full to overflowing with uranium. So at least somebody’s going to get what they want out of this trip, even if Barton really is just as dead as everyone keeps saying. Oh, wait— this is a 1950’s B-movie… Shit. That uranium means the less desolate valleys alongside this one are probably crawling with monsters, doesn’t it? Sure enough! And this being a Bert I. Gordon 1950’s B-movie in particular, those monsters will take the form of extra-big versions of ordinary desert critters. To some extent that entails the expected humongous lizards, snakes, and tarantulas, but there are also a couple of unusual touches like the dog-sized field mouse that Susan and Russ see getting taken out by a hawk only a little smaller than Lee’s plane as their introduction to the plus-sized bestiary of the Tarahuamare Mountains. And as per the title, the big-boss monster of the valley where Barton crashed is a nearly faceless, one-eyed, humanoid giant. Here’s the question, though: the monsters of the mountains are all just ordinary animals sent into pituitary hyperdrive by the radiation from the uranium bed, right? So how do we account for the cyclops? He’d have to be a mutated human, but what would a white man be doing hanging around this middle-of-nowhere wilderness long enough to be radioactively embiggened, seemingly brain-damaged and with half his face torn off? Perhaps we should be reading more into the cyclops’s especial fascination with Susan than just the old “monsters like girls” business that’s been going around since at least the day Andromeda got chained to those rocks for the Ketos…

I guess the closest thing I can offer to a real explanation for my reaction to this film is to say that The Cyclops takes me back. I’m just barely old enough to remember what watching movies at home was like before cable TV and VCRs, when the range of options was drastically narrower, and when movies— and this goes double for movies in specific genres— showed up on television only in certain appointed places, at certain appointed times. Anne Arundel County offered more choices than most markets (we could get both the Baltimore stations and the Washington stations, for a total of twelve reliable channels counting the networks, the independents, and Maryland Public Television), but a kid in search of a monster flick on Saturday afternoon was still going to get only one or at best two rolls of the programming dice until next weekend. The Cyclops, for all its faults, is exactly the sort of movie I would have hoped for back then. One thing Bert I. Gordon did not believe in was dicking around, and those movies he wrote as well as producing and directing tend to be marvels of plotting efficiency. Furthermore, he seems to have approached making his movies with exactly the same mindset that the target audience would eventually bring to watching them— he wanted to get to the monsters as swiftly as possible. In The Cyclops, almost no energy is wasted on the sorts of distractions that frequently plagued films of this kind and vintage. We spend very little time on Susan Winter’s love life, for example. Whereas the makers of Monster from the Ocean Floor or Giant from the Unknown would doubtless have devoted the whole first act to her and Bruce Barton meeting under unusual circumstances and going on cost-conscious dates like walks along the beach or picnics in Bronson Canyon, Gordon has that romance serve only to set the story in motion, and then gets it the hell out of the way. Nor is there any of that “keep the monsters out of sight until the climax” bullshit one deals with so often. Some people might think that’s “suspenseful” (and yeah, okay— from time to time they’re even right), but Gordon knew that nobody ever came to his movies looking for that kind of suspense. Instead, The Cyclops delivers exactly what it promises, in the form of a huge guy with one great, googling eye and only half a face, seen clearly and often— and what’s more, it manages to bring on the monster action early while still keeping the standard build-up to the revelation of the title beastie by thoroughly stuffing the second act with all those lizards, spiders, snakes, and hawks. If you were too young to care that all the creatures were rendered mostly transparent by matting shortcuts, or that the cyclops makeup was as cheap and crappy in execution as it was imaginatively gross in concept, The Cyclops would have seemed just about perfect.

It isn’t only by appealing to my inner eight-year-old that The Cyclops wins me over, though. There are a couple of little things it does that hit me right in my self-made movie critic heart, too. How often, to start with, do you see a crummy old monster flick that works as tragedy? Turn your attention back to where the cyclops could have come from. The natural suspicion is as much as confirmed when the protagonists discover the giant’s lair, and find it strewn with pieces of a small, piston-engined aircraft. Consequently, not only do we understand that Susan and her companions are really battling all that’s left the man they came to rescue when they square off against the cyclops, but so do they. And secondly, I really like the casting of Lon Chaney Jr. as Marty Melville. Chaney could not possibly be any more wrong for the part, but his miscasting is so complete that it circles back around to become kind of brilliant. So far is Chaney’s Melville from the standard profile of a filthy-rich stock manipulator that the performance essentially invites you to look for ways to account for him. I ultimately decided that Melville had to be some kind of Columbo of confidence scams, someone who seems like such a visibly untrustworthy knucklehead that his victims open themselves up to him by guarding against only the simplest and most obvious forms of cheating. When the three men were introduced, I had Chaney pegged as the pilot, and it gave me a moment of pleasurable disorientation when first Lee Brand’s identity and then Russ Bradford’s became apparent: “But that means… Wait— Chaney’s the millionaire?!?!” It doesn’t really seem deliberate, so I don’t want to give Gordon or his casting director too much credit; probably Chaney got the part because Melville is the closest thing The Cyclops has to a human villain, and horror stars presumptively get dibs on the villain’s role. Still, it’s totally unexpected, and the more formulaic a film is otherwise, the more I enjoy seeing it do something totally unexpected, however trivial.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact