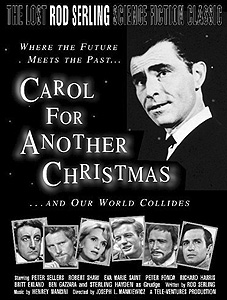

A Carol for Another Christmas (1964) ***˝

A Carol for Another Christmas (1964) ***˝

Of course Rod Serling wrote a version of A Christmas Carol. I mean, come on! Straw-man asshole learns moral lesson after unexpected brush with the paranormal? That’s, like, one out of every three “Twilight Zone” episodes right there. How could he resist the temptation of going back to the source? But when Serling’s time-indexed ghosts talk about peace on Earth and goodwill to man, they have a rather more specific meaning in mind than did Dickens’s. A Carol for Another Christmas was a work-for-hire project for an outfit called the Telsun Foundation (somewhere in southeastern Michigan, one of my regular readers pricks up his ears…)— or, if you’d prefer, the TELevision Series for the United Nations. Telsun’s object was to mount a charm offensive on behalf of the UN, which had become a flashpoint for isolationist and unilateralist elements of the American far right at least as early as the late 1950’s. On the theory that such opposition stemmed mainly from people not understanding what the United Nations actually did, the foundation produced a series of movie-length TV specials designed to tout the importance of international cooperation and diplomacy in a nuclear-armed world, and to highlight the persistent need for an organization with global reach to ameliorate humanity’s age-old problems of hunger, homelessness, and disease. Originally there were to be six such programs, broadcast at monthly intervals, with two airing on each television network. The major financial backer was Xerox Corporation, which committed sufficient sponsorship funds to let each teleplay run uninterrupted by commercials. Only four of the planned specials were actually produced, however (although Telsun does seem to have handled international distribution for the Argentine social justice weepie, Monday’s Child, as well), and two of the three networks got cold feet about inviting boycotts from the UN-hating John Birch Society. The intended monthly broadcast schedule also proved too optimistic by half. Still, the project attracted top talent, both behind and in front of the camera: writers like Serling and Don Mankiewicz, directors like Terrence Young and Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, actors like Peter Sellers and Edward G. Robinson. At one point, even Alfred Hitchcock was reportedly attached to direct an episode!

What’s really curious about Telsun is that at no point was it in the documentary business. Right from the beginning, the plan was to go the Upton Sinclair route, dramatizing the issues by building fictional stories around them. Thus Who Has Seen the Wind? tells the sad tale of a family of war refugees forced to live aboard a tramp steamer. Once Upon a Tractor is a madcap comedy about a peasant in a fictional Communist country who flees to New York City not to defect, but merely to enlist UN aid in browbeating his homeland’s agricultural bureaucracy into replacing his broken-down state-provided tractor. Poppies Are Also Flowers is an espionage thriller (based on a story by Ian Fleming, no less!) about the Iranian opium trade. But for the first installment, slated for broadcast on December 28th, 1964, the foundation naturally wanted something extra-special. Something that would act as a big, flashy statement of purpose, showing what was at stake on all fronts, and exactly where the lines were drawn. Something that would get the point across so forcefully that not even the most willfully thickheaded could fail to get it. And if that was the sort of thing you wanted in 1964, then Rod Serling was definitely the guy you wanted to write it for you.

It’s Christmas Eve, and conservative plutocrat Daniel Grudge (Sterling Hayden, from Venom and The Last Days of Man on Earth) is doing what he usually does this time of year, listening to his dead son’s favorite boogie-woogie records and working himself up into a mood of maudlin pugnacity. This has been going on for 20 years now, ever since Marley was killed in action during World War II. Daniel fought in that war, too, as a mid-level naval officer, but Marley’s death changed his outlook on both the conflict itself and the issues behind it. If you asked him today, he’d tell you that the whole thing was a ghoulish mistake, and that the United States should have left Europe and Asia alone to sort out their own problems. Not that Grudge is some kind of peacenik— far from it. Hell, he practically fetishizes military preparedness. What he has in mind is more of a bunker situation, with Americans squatting suspiciously behind the oceans that separate them from the rest of the world, ready at a moment’s notice to rain thermonuclear hellfire on anyone who looks at them cross-eyed. I’d be very curious to hear how he’d respond to a question like, “Okay, but what about Pearl Harbor?” but nobody ever asks him that.

Grudge’s holiday ritual is intruded upon by his nephew, Fred (Ben Gazzara, of Maneater and When Michael Calls). Fred is a college professor and a liberal internationalist, which in his uncle’s mind makes him the next best thing to Mao Tse Tung (and never you mind what Mao thought of college professors). I gather he doesn’t spend much time with the old man, but tonight he has concrete reason for the visit. The English department at his school had been working for months on a cultural exchange program wherein they and a university in Cracow were to trade professors for a semester. Preparations on each side were in their final stages, when all of a sudden word came down from the college president that the whole thing was off. Something about concerns over the wisdom of exposing young minds to un-American ideas. Fred knew at once what that meant. His uncle is one of the school’s biggest donors, and if he doesn’t like a thing that the faculty is planning to do, then you can count on it not happening. When Fred tries to talk Uncle Dan into minding his own business, it turns into a syllabus of every rancorous political debate to break out in the US since Barry Goldwater arrived on the scene. In fact, if there’s a Fox News faction and a non-Fox News faction in your family, you’ll probably be recreating it across the dining room table yourself this holiday season. It’s not just the paradoxical combination of isolationism and crusading anti-Communism I’ve already described as an element of Grudge’s worldview, either, nor are the expansions confined to the obvious issue of academics and intellectuals acting as disease vectors for dangerous foreign thought. While holding forth about all those things, Daniel also finds time to begrudge the welfare state, to blame poverty on individual laziness, and to deny the existence of systematic oppression in any place that isn’t currently ruled by Marxists. About the only things that don’t get touched on directly are gun control, the civil rights movement, and Christian Dominionism, none of which would become really explosive issues for a while yet when A Carol for Another Christmas was made. Uncle Dan stands his ground, and Fred withdraws in a huff.

That’s when things get weird at the Grudge house. After closing the door behind Fred, Daniel sees Marley (Gordon Spencer, of Joseph Marzano’s Venus in Furs— not to be confused with Jesus Franco’s) reflected in the glass of its upper section, but the dead boy is of course nowhere to be found when Daniel turns around. Then Grudge hears the record player upstairs start up with one of Marley’s Andrews Sisters 78’s, even though there’s nobody up there to turn it on. More disconcerting still, Charles the butler (Percy Rodrigues, from The Legend of Hillbilly John and Come Back, Charleston Blue) says he can’t hear the phantom music. As you probably recognize, these manifestations of Marley are but a prelude to Grudge’s serial visitation by the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Christmas Present, and Christmas Future.

Christmas Past (pop crooner Steve Lawrence) appears to Grudge in the guise of a World War I infantryman of the American Expeditionary Force. Appropriately enough, Daniel suddenly finds himself on the deck of a transport ship laden with coffins of the war dead, the cargo silently watched over by an honor guard of shades decked out in the military uniforms of a dozen nations. Despite the unfamiliar setting, though, Grudge is on his home turf arguing with the ghost that none of his era’s deadly foolishness in Europe was America’s problem, and that the spilled blood of the men in whose shape the ghost appears was squandered on the unworthy ingrates of the Old World. Curiously, the ghost doesn’t mention the Lusitania. He does, however, bring up the submarine, the guided missile, and the intercontinental jet bomber, pointing out how illusory the isolative power of the oceans surrounding the Americas has become. He also attempts to explain how Grudge’s preferred solution to the problem— heavily armed seclusion— means abandoning the ancient wisdom that so long as people are talking, they’re not throwing punches. Then, to remind Daniel what throwing punches on an international scale looks like today, the ghost exchanges a general and metaphorical past for a specific and concrete one: that day in August of 1945 when Grudge’s ship called at what was left of Hiroshima, and he saw with his own eyes the power of the atom bomb. It’s easy to speak in broad, self-righteous platitudes about the foreign enemy, but somewhat less so when the abstractions of geopolitics resolve themselves into a hospital ward full of schoolgirls with their faces melted off.

Christmas Present (Pat Hingle, from Nightmare Honeymoon and Tarantulas: The Deadly Cargo) is only tangentially concerned with matters of war and peace. After all, armed conflict in 1964 was a localized, small-scale phenomenon, occurring in parts of the world beneath the notice of men like Daniel Grudge. Indeed, it’s that very issue of notice that the ghost wants to discuss. Christmas Present sits alone at the head of a banquet table, complaining as he gorges himself that part of him is always hungry, no matter how satisfied the rest of him becomes. It’s the human condition, really, not just in the metaphorical sense that a rich businessman like Grudge can instinctively understand, but also quite literally. Think about the harvests of all the world’s cropland; think about how much of that bounty goes to waste because the developed world produces more than it can ever use, while millions upon millions in less fortunate regions starve. And think about this, the ghost says, gesturing into visibility a displaced persons camp in what I take to be the Balkans. Twenty years almost after the war’s end, life still isn’t back to normal for many of its victims— and before Grudge blathers anything about pulling themselves up by their bootstraps, let him observe that these people would be lucky to afford boots in the first place. Grudge gets a bit high-horsey here, demanding to know how the ghost can keep stuffing himself with that going on right in front of him, but Christmas Present counters that the only difference between what he’s doing now and what Daniel does every day is the “right in front of” bit. Grudge has the option of looking elsewhere, and exercises it freely, but for an omnipresent spirit, there’s no such thing as out of sight.

The future segment is always where versions of this story bring their A-games, and A Carol for Another Christmas is no exception. Grudge meets the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come (Robert Shaw, of Jaws) in the bombed-out ruin of his town’s meeting hall. The spirit can’t tell him what year it is, because nobody saw much point in calendars after they shot the nukes. He can’t see what Daniel’s so upset about, either, since it was men like him getting their way that brought all this to pass. No more talking with the enemy, no more entertaining foreign ideas, no more coddling the shiftless weak or sacrificing for the so-called common good. Just peace through power and rugged individualism— and if peace through power became peace through annihilation, well… better dead than red, right? There were some survivors, of course. Not even the Permian Extinction killed everything. And as Grudge will no doubt be pleased to see, they’ve carried his philosophy to a whole new level. In fact, here come some of them now, assembling for a session of the Non-Government of the Me People.

I don’t know how else to say this— it’s a Tea Party rally. While the small crowd cheers ecstatically, a smirking clown of a demagogue calling himself the Imperial Me (Peter Sellers, in a performance that could almost have been an outtake from Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb) is borne in on a saddle-backed litter by a quartet of football players. He wears a rhinestone-bedazzled cowboy hat (some of the bling spells out “ME”) with the top cut to resemble a crown and a dark velour tunic with a white Puritan collar. Taking up a position behind the dilapidated lectern, he warns his followers of a dastardly plot by the people “down yonder and cross river” to infringe upon the God-given rights of the Individuals Mes by talking and debating about “what they call our ‘common problems’.” The crowd sneers and catcalls “Unpatriotic!” as the Imperial Me warms to his subject, condemning such discussion as surrender and extolling by contrast the strength and wisdom of the Me People. He rapturously describes a future, now close at hand, in which only the very strongest will be able to exist, and society itself will wither away into a scattering of sovereign individuals, each all-powerful within his or her sphere of armed autonomy. I don’t know where Serling got his crystal ball, but if he were still alive, he’d have a thousand shyster psychics bugging him for the vendor’s business card. Only one dissenting voice is heard from among the Mes— that of Grudge’s old butler. Coming forward to contest what he calls the demagogue’s insanity, Charles calls for a return to brotherhood, cooperation, and mutual responsibility. His exhortations don’t go over well. Eventually, a little boy with an enormous pistol shoots Charles dead while his mother (Britt Ekland, of Asylum and The Monster Club) looks on approvingly. Grudge is aghast, but seems to grasp only partly the point that this band of maniacs has merely extrapolated his own opinions to their logical conclusion. In A Carol for Another Christmas’s smartest move, it ends not with a full Dickensian conversion, but merely with Grudge beginning a tentative rethinking of his former stances. We don’t even know whether Fred will get his cultural exchange program reinstated.

A Carol for Another Christmas represents Rod Serling at his most flagrantly messianic. It is shamelessly polemic, thuddingly obvious, and completely without tact or subtlety of any kind. Probably it will convince no one who doesn’t already agree with it, and certainly it was received very poorly in its initial— and for almost 50 years only— broadcast. Naturally it riled up the Birchers whom it overtly ridiculed, but it also took a kicking from liberal critics who rightly considered it both crude and ungenerously one-sided. That was 1964, though, when it was uncontroversial to assert that there was and should be this thing called “society,” in which people would sometimes be expected to put aside their narrow self-interest for the greater and common good. That was before “let people who don’t have health insurance die” became a sufficiently mainstream position to be shouted by spectators at a major political party’s presidential primary debates. That was before the intellectual heirs of the real-life Daniel Grudges came out, in as many words, against the concept of empathy. Unsubtle as it is, the main problem with A Carol for Another Christmas is that it was about five decades ahead of its time.

Mind you, it helps that A Carol for Another Christmas is such a technical tour de force. Sterling Hayden, Peter Sellers, Robert Shaw, Ben Gazzara, and even Percy Rodrigues were such pros that they could sell practically anything, and director Joseph Mankiewicz was no quickie hack, either. Steve Lawrence, in his first-ever acting gig, is remarkably self-assured, hitting just the right note of easy artificiality in a part defined by the jarring speech patterns and mannerisms of an extinct form of cool. The scale of the production is TV-small, certainly, but Mankiewicz makes that work for the film by turning it into a manifestation of the ghosts’ outside-of-reality existence. It’s truly impressive what this movie can do with a nearly empty soundstage, some spotlights, and a fog machine. There’s some nicely understated trick cinematography, too— real old-school stuff involving differential lighting and sheets of plate glass angled just right. The look of the picture is that rich, moody black and white that the 40’s forgot and the 50’s scorned, except in the ghetto of film noir. Put it all together, and you get a production that rises far above Serling’s shrill yet depressingly prescient preaching.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact